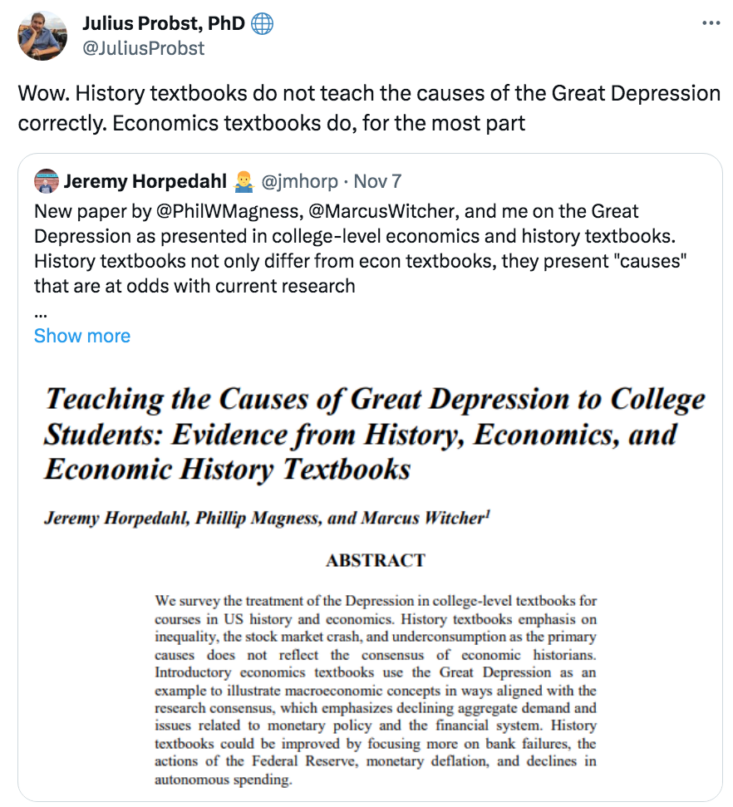

"The following tweet caught my eye:

I once wrote an entire book on the causes of the Great Depression, focusing on the role of the interwar gold standard and FDR’s labor market policies. In doing this research, I discovered that the question of causation is quite tricky. One can look for proximate causes, such as bad macroeconomic policy, or deeper causes, such as institutional failures. (In theory, a depression might also be caused by a natural phenomenon such as a plague or drought, but that was not the case with the Great Depression. It was clearly a human created problem.) Although we do not precisely know all of the factors that caused the Great Depression, we have a pretty good idea as to which hypotheses are not helpful.Many people associated the stock market crash with the Depression due to the fact that it occurred at about the time it became apparent we were sliding into a deep slump. Note that I said “became apparent”; the Depression actually began a few months before the crash. In October 1987, we had a nice test of the theory that the stock crash was a causal element in the Depression. A crash of almost equal size occurred at almost exactly the same time of year, after a long economic expansion. Many pundits expected a depression, or at least a recession. Instead, the 1987 stock market crash was followed by a booming economy in 1988 and 1989.

Of course it’s possible to explain some difference in outcome to other factors at play, but when the difference is this dramatic (booming economy vs. the greatest depression in modern history), one has to wonder whether the hypothesis is of any value at all.

The same is true of the inequality/underconsumption hypothesis. Over the last 45 years, we’ve seen an interesting test of this theory. China has experienced a huge increase in economic inequality. More importantly, it has seen some of the lowest levels of consumption (as a share of GDP) ever observed. Even lower than other fast growing East Asian economies such as South Korea. Pundits have claimed that China’s consumption levels are too low, and that too many resources are being devoted to investment in areas of dubious merit.

That may all be true. Perhaps China should invest less and consume more. But it’s also clear that low levels of consumption in China have not caused a Great Depression. Indeed China’s had one of the fastest growing economies in the world since 1978.

Again, what impresses me about these two counterexamples (the US in 1987-89 and China since 1978) is not that things didn’t play out exactly as the historians might have expected based on their theory of the Great Depression. Rather what impresses me is that the results were almost 180 degrees removed from what might have been expected. That tells me that theories that stock market crashes and underconsumption cause depressions are essentially useless. They are ad hoc explanations with no real supporting economic theory and no predictive power. Why should a stock market crash cause 25% of workers to stop working? What is the mechanism? Why should high levels of investment cause real GDP to decline by 30% over 4 years? What is the mechanism? If they have no theoretical support and no predictive power, then why should we care what historians believe?

If you get creative enough you could find a causal mechanism running through aggregate demand. But then why not argue that a decline in aggregate demand caused the Great Depression? After all, that’s what actually did happen.

You might say that it’s important to know the cause of the Great Depression. But why? If the theories offered by historians provide no help in understanding the modern world, then how are they of any use?

More broadly, I distrust all theories of economic causation developed by non-economists (not just historians). These theories tend to rely on “common sense”. Thus many average people think that countries are rich because they are big, or because they have lots of natural resources. (Perhaps because that theory sort of fits the US.) But looking more broadly, rich countries don’t tend to be places with large populations or high levels of natural resources. They tend to be smaller countries in East Asia and Western Europe. The actual (institutional) factors that explain the varying wealth of nations are much harder to see, and hence tend to be ignored by non-economists."

Related post:

Monetary Policy and the Great Crash of 1929: A Bursting Bubble or Collapsing Fundamentals?

Conclusion

In retrospect, it seems that the lesson of the Great Crash is more

about the difficulty of identifying speculative bubbles and the risks

associated with aggressive actions conditioned on noisy observations. In

the critical years 1928 to 1930, the Fed did not stand on the sidelines

and allow asset prices to soar unabated. On the contrary, its policy

represented a striking example of The Economist’s

recommendation: a deliberate, preemptive strike against an (apparent)

bubble. The Fed succeeded in putting a halt to the rapid increase in

share prices, but in doing so it may have contributed one of the main

impulses for the Great Depression."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.