"Labor unions are entitled to their opinions on public policy, but not their own facts.

In California right now, the Service Employees International Union, or SEIU, is using bogus data and false claims to enhance its efforts to organize restaurant workers. Congress needs to pay attention because what happens in California doesn’t stay there for long.

Last year, Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 257, an SEIU-backed scheme to create an unelected council of union appointees to regulate workplace standards for fast-food outlets. The union justified its proposal with a report claiming that these businesses were uniquely bad violators of state labor law.

Yet data from the state’s own Department of Industrial Relations debunked this argument. According to an analysis of the data by the Employment Policies Institute (EPI is managed by Berman and Co.), fast-food businesses account for just 1.6% of all reported wage violations, up to five times lower than other industries.

That inconvenient truth didn’t keep the Legislature from passing AB 257, but their constituents may have other ideas: This past fall, over a million California voters signed petitions to halt the law and place it on the ballot as a referendum in 2024.

Instead of listening to the reasonable voices of voters, the SEIU ignored them.

This year, it returned with AB 1228, known as the Fast Food Franchisor Responsibility Act, which would create joint liability between an independent small-business owner (franchisee) who owns a recognizable brand and the company that establishes the brand’s trademark (franchisor).

In simple terms, the bill would force countless small businesses in the state to close their doors while forcing job cuts and higher prices at those that remain open.

In a flashback to last year’s debunked claims, the SEIU implied that franchisees in the fast-food industry are uniquely likely to commit wage violations against their employees. Yet again, the state’s own data rejects this narrative. Statewide records of alleged wage violations show that franchisee-owned fast-food outlets represent just two-thirds of 1% (0.65%) of wage violation claims in the state.

In actual investigations where the state fined employers, fast-food franchises were responsible for an even lower share — just 0.41% of claims statewide.

By using bogus data to promote myths about the state’s fast-food industry, the SEIU and other activists are crippling California’s business environment. The state’s hospitality industry is still reeling from the consequences of the SEIU’s fight for a $15 hourly minimum wage. The union justified the then-radical demand using comforting studies from its allied economists, who argued that a $15 minimum could easily be absorbed by the state’s employers.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the state’s restaurant employment growth rate dropped by more than two-thirds over the last decade and has struggled to rebound from the pandemic. Despite 16-to-19-year-olds making up the largest share of restaurant employees, Census Bureau data shows California’s teen unemployment rates are already well above the national average.

Studies from Harvard, the University of California, Irvine, and others have shown clear evidence of the job loss and business closing consequences of radical wage laws.

California’s ideas will soon come to Congress. Next month, Sen. Bernie Sanders will hold a vote on a proposed $17 minimum wage, inspired by California and other states that have embraced this mandate. Further attacks on the hospitality industry aren’t far behind. If the union-backed research introduced to support these proposals sounds too good to be true, it probably is."

Wednesday, May 31, 2023

Union myths drive bad public policy on fast-food industry

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

"In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

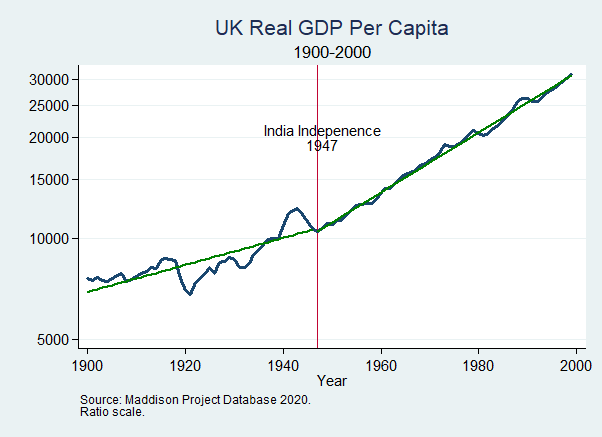

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity."

Tuesday, May 30, 2023

ESG Defenders Pose as ‘Free Market’ Disciples

Activists and bureaucrats seek to deny capital to companies and whole industries via blacklists

By Steve Marshall. He is attorney general of Alabama. Excerpts:

"America’s self-proclaimed “socially responsible” financial institutions, which should be competing in the free market, are instead joining forces with one another and their global counterparts to decide which companies—and, in some cases, which industries—should be permitted to continue their market participation unimpeded.

Since 2017, a growing number of these financial alliances, including Climate Action 100+, the Net-Zero Banking Alliance and the Venture Climate Alliance, have plotted to pressure blacklisted companies into making a priority of decarbonization and other social goals at the behest of the United Nations, not American consumers. In other words, by controlling trillions of dollars in assets, these groups intend to corner the market through potentially illegal horizontal agreements and force preferred social and political objectives on American companies and consumers.

The Net Zero Asset Managers initiative boasts 301 signatories and $59 trillion in assets under management. On its website, the group writes: “Our industry’s ability to drive the transition to net zero is extremely powerful. Without our industry on board, the goals set out in the Paris Agreement will be difficult to meet.”

This statement doesn’t refer to a company making a business choice because of consumer demand or shareholder interest. Rather, it reveals a coalition of major financial-industry players that have come together to choke out certain disfavored companies and industries by limiting their access to capital and then pointing to this manufactured obstruction as evidence that these firms are a bad investment. The resulting harm to the working public—of little interest to global elites—is higher energy costs and fewer options across a variety of markets, including automobiles, appliances and food production."

"Opposite us in these efforts is Joe Biden, whose presidency has been an ESG crusade in the crudest form. Mr. Biden is attempting to create the federal government’s own version of Climate Action 100+ by imposing emissions disclosures and other ESG litmus tests on federal contractors without the approval of Congress. The president would then have his own blacklist, useful for strong-arming companies to go woke in defiance of market forces and the legislative branch."

If Your Toddler Isn’t Talking Yet, the Pandemic Might Be to Blame

Children who spent little time socializing are talking later and treatment is scarce

By Sara Toy of The WSJ. Excerpts:

"Babies and toddlers are being diagnosed with speech and language delays in greater numbers, part of developmental and academic setbacks for children of all ages after the pandemic. Children born during or slightly before the pandemic are more likely to have problems communicating compared with those born earlier, studies show."

"In an analysis of nearly 2.5 million children younger than 5 years old, researchers at health-analytics company Truveta found that for each year of age, first-time speech delay diagnoses increased by an average of 1.6 times between 2018-19 and 2021-22. The highest increase was among 1-year-olds, the researchers said.

Social isolation coupled with pandemic-related stress among parents likely contributed to the delays"

"Families were less likely to start therapy or get their children evaluated during the pandemic"

"nearly 80% of speech-language pathologists were seeing more children with delayed language or diagnosed language disorders than before the pandemic. Nearly four in five reported treating more children with social-communication difficulties than before the pandemic."

"The lack of socialization likely contributed to their speech and language delays"

Why Cancer Drugs Are Being Rationed

The government squeeze on generic profits is leading to shortages

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists lists 301 drugs in short supply, up from 202 five years ago. These include many local anesthetics, basic hospital drugs, chemotherapy drugs and liquid albuterol for lung ailments.

The American Cancer Society warned this month that “first-line treatments for a number of cancers, including triple-negative breast cancer, ovarian cancer and leukemia often experienced by pediatric cancer patients,” are facing shortages that “could lead to delays in treatment that could result in worse outcomes.” Healthcare providers say they’re having to limit access to some drugs to the sickest patients. They can substitute therapeutic alternatives when possible, but this increases risk of medication errors and inferior results. What’s going on?"

"most drugs in short supply are older generics that are off-patent and complicated to make. Manufacturers have stopped producing them because profit margins are too thin, resulting in one or two suppliers."

"Fewer branded drugs are in short supply because their manufacturers build more slack and resilience into supply chains. Higher profits give them more capital and a financial incentive to do so. And therein lies the underlying problem: Generic profits have shriveled owing to government efforts to reduce drug spending."

"low Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates have increased pressure on providers to lower costs."

"Mandatory Medicaid rebates have also squeezed generic drug margins. Medicaid is the top payer for many generic drugs. But low reimbursements by government health systems are a global problem, and manufacturers with plants in Europe cut production amid last year’s energy price spike."

"Politicians criticize generic companies for shifting production to India and China to reduce costs, but the alternative for many would be to go out of business, as Illinois-based Akorn Pharmaceuticals did this winter."

"The solution is for government to pay more for drugs, which politicians oppose because it will increase healthcare spending."

"The Inflation Reduction Act requires manufacturers of single-source generics and branded drugs to pay Medicare rebates if prices rise faster than inflation. This limits manufacturers’ ability to pass on rising costs and invest in supply resilience and quality control. Medicare “negotiations”—i.e., price controls—will also shrink brand drug margins."

SVB’s Greg Becker Tells His Story

The failed bank was responding to incentives created by the Fed

"Federal regulators blame bad management and lax regulation for Silicon Valley Bank’s failure. On Tuesday former Silicon Valley Bank CEO Greg Becker gave the Senate his side of the story, filling in crucial details left out of the Federal Reserve’s self-examination last month.

By Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr’s telling, SVB grew too big too fast. Executives prioritized growth over risk management while ignoring repeated warnings by examiners. Supervisors didn’t come down hard enough and were handicapped by a 2018 law that eased regulation on midsize banks.

Mr. Becker explains what the Fed would prefer to ignore. Deposits ballooned during the pandemic owing to “near-zero interest rates and the largest government-sponsored economic stimulus in history,” Mr. Becker told Senators. Liquidity and capital rules encouraged SVB to invest its flood of new deposits in long-dated government-backed securities that regulators deemed “safe.”

“Throughout 2020 until late 2021, the messaging from the Federal Reserve was that interest rates would remain low and that the inflation that was starting to bubble up would only be ‘transitory,’” Mr. Becker said. Then the Fed flipped on a dime and rapidly raised rates to subdue inflation in 2022, catching SVB and some other banks off guard.

Around the same time, SVB found itself subject to new regulations for “Large Financial Institutions,” which consumed significant resources and attention. “I met regularly, and often monthly, with SVB’s regulators, including examiners, to discuss strategy, organizational changes, personnel changes, our initiatives, and address any regulatory issues or concerns,” Mr. Becker noted.

“From 2020 to 2022, our headcount and professional services expenses increased substantially, the bulk of which were dedicated to enhancing risk management and operational execution,” he added. “By the end of 2022, my recollection is that SVB had roughly 1,000 people with all, or the majority, of their responsibilities focused on risk management of some type.”

A lack of attention to regulation can hardly be faulted for SVB’s failure. Mr. Becker’s testimony suggests that bank examiners and SVB employees were focused more on complying with regulation than managing actual and potential balance-sheet risks. Examiners were concerned primarily with SVB’s processes, not its classic financial vulnerability of interest-rate risk hiding in plain sight.

Bank executives aren’t blameless, but they were also responding to the Fed’s easy money and misplaced regulatory priorities. Mr. Becker has lost his job and no doubt a lot of money. Has even a single regulator at the San Francisco Fed lost hers?"

Monday, May 29, 2023

IRS Needs a Cage, Not More Cash

The cases of the whistleblower Gary Shapley and journalist Matt Taibbi show why the GOP should claw back that $80 billion infusion

By Kimberley A. Strassel. Excerpts:

"This week brought two more examples of IRS roguery that build on its already unsavory record of leaks, incompetence and partisan behavior. The first is the alarming story of journalist Matt Taibbi, who may have been targeted by the IRS in retribution for documenting the joint censorship efforts of Big Tech and the federal government.

Mr. Taibbi in March told the House Judiciary Committee a disturbing tale: an IRS agent had made a surprise visit to his New Jersey residence on March 9—the same day Mr. Taibbi testified before another House committee about censorship at Twitter. The journalist was subsequently told there were “identity theft” concerns with his 2021 and 2018 tax returns. The 2018 claim particularly troubled Mr. Taibbi, since his accountants possessed documentation showing the return had been electronically accepted, and neither they nor he had ever received notification of a problem. Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan demanded the IRS explain.

The IRS earlier this month provided Mr. Jordan documents that only add to the appearance of targeting. It seems the IRS officially opened its examination of Mr. Taibbi’s return on Dec. 24—not only Christmas Eve but a Saturday. What could be urgent enough to inspire a government employee to work overtime? That was the day Mr. Taibbi capped three weeks of reporting with his ninth installment of the Twitter files, an exposé of a wide sweep of federal agencies working with social-media companies to censor online speech.

Documents also show that in addition to the unannounced house call, an IRS agent dived deep into Mr. Taibbi’s personal life, compiling a file of his voter-registration records, whether he had a concealed-weapon permit and even whether he possessed hunting or fishing licenses, among other data. The file contained his Wikipedia page detailing his Twitter files work. The IRS launched this excavation even though Mr. Taibbi didn’t owe the IRS any money.

More notable is what the IRS didn’t provide the House: any proof of letters it claimed to have sent to Mr. Taibbi alerting him to the purported 2018 problem. It also failed to cough up internal communications related to the case, despite Mr. Jordan’s demand and Mr. Taibbi’s signed waiver to allow Congress to see information related to his return."

"Then there’s IRS Supervisory Special Agent Gary Shapley, the congressional whistleblower who this week went public with his claims of Justice Department political interference in the Hunter Biden probe. A 14-year IRS veteran, Mr. Shapley oversees a team that specializes in international tax and financial crimes. He says he was assigned control of the Biden investigation in 2020, but again and again watched prosecutors engage in “deviations” from the normal process, in ways that “seemed to always benefit the subject.” He explained he “couldn’t silence my conscience anymore.”

Mr. Shapley’s attorneys informed Congress that their client and his team had recently been yanked off the probe “at the request of” the Justice Department—which looks like clear (and forbidden) retaliation for his speaking out. IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel will undoubtedly try to slough this off on Justice, but a request is only a request, and nothing excuses Mr. Werfel from his own obligation to see tax justice done or protect whistleblowers. The IRS can hardly claim to need more money to pursue tax cheats when it is sidelining top investigators pursuing tax cheats."

The Big Meat Conspiracy Theory Unravels

Tyson Foods loses money, which doesn’t sound like a monopoly

"Remember when President Biden and progressives last year accused meat packers of colluding to fatten their profits. Are they now conspiring to lose money? Tyson Foods last week reported its first quarterly loss since 2009 as meat prices tumbled. Here’s a lesson in market economics, Mr. President.

Tyson’s stock plunged after it reported anemic sales and downgraded its forecast. The quarterly loss at the largest U.S. meat supplier marks a stunning reversal from 2021 and early last year when it earned record profits amid a run-up in meat prices. What happened?

Well, meat supply increased as packers ramped up production and increased wages for employees to meet demand. But producer costs for cattle and chicken have remained elevated. At the same time, consumer demand for pricier cuts of beef and pork has declined as inflation ate into purchasing power. All of this has shrunk Tyson’s margins.

As we explained in “Carving Up Biden’s Inflation Beef” (Jan. 7, 2022), the gusher of pandemic transfer payments swelled demand for more expensive meat products and contributed to a labor shortage that constrained production. When demand exceeds supply, business margins increase as markets ration scarce goods via prices.

Yet Democrats alleged a corporate conspiracy. Mr. Biden claimed that rising meat prices and profits reflect “the market being distorted by a lack of competition” and “capitalism without competition isn’t capitalism; it’s exploitation.” Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren accused Tyson of abusing its “corporate market power and raking in record profits by jacking up meat prices.”

If markets were “distorted,” the culprit was pandemic transfer payments that were a disincentive to work. As these programs lapsed, hiring became easier. Competition for workers and market share raised supplier costs while pushing down prices and profits. Meat prices fell 0.4% in April and are up only 0.3% over the past 12 months.

Tyson’s stock has fallen by nearly half over the past year and is trading at the lowest levels since 2015. This doesn’t look like an antitrust conspiracy or market oligopoly, but the meat packers and their shareholders will never get an apology from Washington."

Sunday, May 28, 2023

In New York Prisons, Guards Who Brutalize Prisoners Rarely Get Fired

Records obtained by The Marshall Project

reveal a state discipline system that

fails to hold many guards accountable

By Alysia Santo, Joseph Neff and Tom Meagher of The NY Times. Excerpts:

"Shattered teeth. Punctured lungs. Broken bones. Over a dozen years, New York State officials have documented the results of attacks by hundreds of prison guards on the people in their custody."

"when the state corrections department has tried to use this evidence to fire guards, it has failed 90% of the time"

"more than 290 cases in which the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision tried to fire officers or supervisors it said physically abused prisoners or covered up mistreatment that ranged from group beatings to withholding food. The agency considered these employees a threat to the safety and security of prisons.

Yet officers were ousted in just 28 cases. The state tried to fire one guard for using excessive force in three separate incidents within three years — and failed each time."

"An officer who broke his baton hitting a prisoner 35 times, even after the man was handcuffed, was not fired. Neither were the guards who beat a prisoner at Attica Correctional Facility so badly that he needed 13 staples to close gashes in his scalp. Nor were the officers who battered a man with mental illness, injuring him from face to groin. The man hanged himself the next day.

In dozens of documented cases involving severe injuries of prisoners, including three deaths, the agency did not even try to discipline officers"

"For decades, the workings of the prison discipline system had been hidden from public view under a secrecy law adopted at the urging of the state’s powerful law enforcement unions."

"The records probably reflect only a fraction of the violence guards have inflicted in New York’s corrections system, experts said. Many prisoners do not file complaints because they fear retaliation or not being believed."

"the contract the state signed in 1972 with the union. The agreement requires any effort to fire an officer to go through binding arbitration, using an outside arbitrator hired by the union and the state"

"Only a court can overturn arbitration decisions.

In abuse cases, the arbitrators ruled in favor of officers three-quarters of the time"

"verall, the corrections department has tried to oust staff members almost 4,000 times since 2010, for such infractions as chronic tardiness and drug use. It succeeded in just 7% of the cases."

"In 2016, The New York Times reported that state officials vowed to beef up investigations into brutality after an arbitrator reinstated an officer with back pay even though the guard had been caught on video repeatedly punching a prisoner lying on the floor. A jury acquitted the guard of assault, however, and attacks on prisoners continued.

Two years later, Gov. Andrew Cuomo pushed legislation to give the corrections commissioner the power to dismiss officers, but the plan withered under opposition from the Assembly and Senate."

"A powerful union can undermine safety in prisons by gumming up the disciplinary process, said Steve J. Martin, who has worked as a consultant for corrections facilities across the country and is now the court-ordered monitor for the New York City jails on Rikers Island.

Officers “know they can beat the system more often than not,” Martin said. “That’s how you develop these cultures where you have frequent instances of excessive force.”"

"The Marshall Project identified more than 160 excessive-force lawsuits that the state lost or settled, paying $18.5 million in damages. The corrections department’s records show that officials attempted to discipline an officer in just 20 of those cases."

"The attack that prompted Nick Magalios to file his lawsuit began when officers at Fishkill Correctional Facility, in New York’s Hudson Valley, yelled at him for hugging and kissing his wife hello during a visit, which prison rules allowed.

Afterward, Officer Mathew Peralta, who had reprimanded Magalios, knocked him to the floor and kicked and punched him as another guard held him down and a third officer watched, according to testimony in the civil trial."

"The Marshall Project found only two excessive force lawsuits in which officers had to contribute some of their own money; taxpayers were on the hook for the rest."

Make Welfare Reform Part of the Debt-Ceiling Deal

The Clinton-era law added work requirements, but politicians since have chipped away at them

By Jason L. Riley. Excerpts:

"In the late 1980s and early 1990s, welfare dependence grew by a third as people figured out that they could receive more in public benefits than they could earn in the labor force. When Bill Clinton joined forces with a Republican Congress in 1996 to pass a welfare-reform bill that included work mandates, party leaders from Ted Kennedy to Pat Moynihan and Dick Gephardt predicted social carnage. Yet by the end of the decade, the welfare rolls had fallen by more than 50% nationwide. Poverty rates among blacks and female-headed households—groups with disproportionately high welfare-use rates—also plunged.

Since then, lawmakers have chipped away at those reforms, usually in the wake of an economic downturn. Under Democratic and Republican administrations, unemployment insurance has been expanded and work requirements have been suspended. The public is assured that the changes will be temporary, but they seldom are."

"The unemployment rate has reached historic lows, and wages have been rising, including among historically marginalized groups. A headline in Friday’s Journal read “Job Market for Black Workers Is Best Ever.” Black unemployment was a record low 4.7% in April, and the number of blacks in the labor force today is some 1.1 million higher than it was before the pandemic. “Black workers have long been at the bottom of the ladder in terms of wages and job security,” the story noted. “But the confluence of strong demand for labor and demographic shifts in the country over the past few years, when many older white workers retired, benefited Black Americans.” If now isn’t the time to rethink qualifications and requirements for public assistance, when is?

Too many healthy adults are opting out of work because public policy has made unemployment too attractive. As Mr. McCarthy has noted, Joe Biden once understood this. As a senator, he was among the Democrats who supported the 1996 welfare reform."

"Republicans say the reforms will help cut costs, and a Congressional Budget Office analysis predicted savings of more than $100 billion over 10 years."

Saturday, May 27, 2023

Supreme Court Clarifies Murky “Waters of the United States” Definition: It No Longer Includes Mud Puddles

By Jay Schweikert and Isaiah McKinney of Cato.

"This week, in Sackett v. EPA, the Supreme Court closed the book on Mike and Chantell Sackett’s 19 year saga of trying to build on their land. In 2004, the Sacketts purchased property 500 feet from the shores of Priest Lake, Idaho. In 2007, after they started to fill in wet spots in their property so they could build a home, EPA officials informed the Sacketts that their property was a wetland adjacent to a tributary that fed into the lake, and therefore counted as “navigable waters” under the EPA’s jurisdiction pursuant to the Clean Water Act (“CWA”). The Sacketts would need to get a permit if they wanted to build, and a permit, if the Sacketts could get one, would cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars. The Sacketts challenged the EPA’s decision, but the lower court decided the EPA’s order was not “final,” so the Sacketts could not challenge it. The Sacketts appealed, eventually going to the Supreme Court in 2012, which held that the EPA’s decision was a final order and the Sacketts were able to challenge it.

11 years later, the Sacketts were back at the Supreme Court, this time asking whether their property could be regulated as “waters of the United States” under the CWA. This is the fourth time the Supreme Court has addressed the scope of this provision—and this time the Court got it right.

The story of CWA regulation and litigation is too long and confusing to tell here in full. But the last time the Supreme Court addressed the scope of “navigable waters”—which the statute further defines as “waters of the United States”—in 2006, the Court split 4–1‑4, so there was no controlling majority. The two main opinions from that case, Rapanos v. United States—written by Justices Scalia and Kennedy respectively—disagreed on the test that should be applied to determine if a wetland was “waters of the United States.” Justice Scalia’s test would apply to “permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water,” and wetlands that shared a “continuous surface connection” to such permanent bodies of water. Justice Kennedy considered this term more broadly to include all bodies of water that had a “significant nexus” with navigable‐in‐fact waters.

Lower courts split on which test to apply, but most courts applied Justice Kennedy’s broader test. One of the issues with his test, however, was that “significant nexus” had no real limiting principle. Land that was in no way connected to navigable waters, but which was damp for a couple months of the year, could be regulated as “waters of the United States” because sufficient water molecules from that land interacted with nearby bodies of water. Justice Kennedy’s test was indeed expansive.

This week, the Court unanimously rejected the significant nexus test and held that the EPA lacked jurisdiction to prohibit the Sacketts from building on their land. Justice Alito, writing for the majority, essentially adopted Justice Scalia’s test from Rapanos. Quoting from Justice Scalia’s opinion, Justice Alito explained that the term “waters of the United States” is limited to “only those relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water forming geographical features that are described in ordinary parlance as streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes.” But amendments to the CWA, in a provision discussing permits, state that the EPA can regulate not only “waters of the United States,” but also “adjacent wetlands.” These “adjacent wetlands” must not be distinct and separate from “waters of the United States,” Alito explained, because otherwise the amendments would be drastically changing the scope of the statute via an ancillary provision. Congress was not changing the scope of the CWA by allowing permits for wetlands. Rather an “adjacent wetland” is an “indistinguishably part of a body of water that itself constitutes ‘waters’ under the CWA.” Therefore, as Scalia wrote in 2006, “adjacent wetlands” must be connected to navigable waters via “a continuous surface connection.”

This decision brings clarity to an area of the law that has been infamously obtuse. The scope of the CWA has bounced back and forth for decades, leaving farmers, homebuilders, and property owners across this country in confusion on what they can and cannot do on their property. Not only did the Supreme Court pen a happy ending for the Sacketts—they will now get to build their dream home—but property owners everywhere have received much needed clarity on whether their property qualifies as “waters of the United States.” Not only did property rights win the day, but so also did clarity and simplicity."

Work requirements

"The debate over work requirements for social programs is hot and heavy. I'll chime in there as I don't think even the Wall Street Journal Editorial pages have stated the issue clearly from an economic point of view. As usual, it's getting obfuscated in a moral cloud by both sides: How could you be so heartless as to force unfortunate people to work, vs. how immoral it is to subsidize indolence, and value of the "culture" of self-sufficiency.

Economics, as usual, offers a straightforward value-free way to think about the issue: Incentives. When you put all our social programs together, low income Americans face roughly 100% marginal tax rates. Earn an extra dollar, lose a dollar of benefits. It's not that simple, of course, with multiple cliffs of infinite tax rates (earn an extra cent, lose a program entirely), and depends on how many and which programs people sign up for. But the order of magnitude is right.

The incentive effect is clear: don't work (legally). As Phil Gramm and Mike Solon report,

Since 1967, average inflation-adjusted transfer payments to low-income households—the bottom 20%—have grown from $9,677 to $45,389. During that same period, the percentage of prime working-age adults in the bottom 20% of income earners who actually worked collapsed from 68% to 36%.

36%. The latter number is my main point, we'll get to cost later. Similarly, the WSJ points to a report by Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram at the Foundation for Government Accountability that

there are four million able-bodied adults without dependents on food stamps, and three in four don’t work at all. Less than 3% work full-time.

3%.

Incentives are a budget constraint to government policy, hard and immutable. Your feelings about people one way or another do not move the incentives at all. A gift of money with an income phase-out leads people to work less, and to require more gifts of money. That's just a fact.

What to do?

One answer is, remove the income phaseouts. Give food stamps, medicaid, housing subsidies, earned income tax credits, and so forth, to everyone, and don't reduce them with income. Then the disincentive to work is much reduced. (There is still the "income effect," but in my judgement that's a lot smaller for most people in this category.)

Rather obviously, that's impractical. Even the US, even if r<g or MMT are true, would run out of money quickly. That's the problem with Universal Basic Income. Even $20,000 x 331 million = $6.6 trillion, essentially the entire federal budget right there, and $20,000 of total support is a lot less than people with $0 income get right now. (Gramm, Ekelund and Early, and Casey Mulligan estimate about $60,000 is the right number here.) Put another way, to eliminate the work disincentive in the social programs, we would have to jack up marginal tax rates on everyone to such stratospheric levels that nobody works. You can't escape disincentives.

So, support for the unfortunate must be limited somehow. That's why we limit it to people below a certain income level. But even if each individual program maintains a reasonable marginal phaseout, they add up across programs, and next thing you know we're back to 100% phase out.

Posit that work is still desirable, to earn some money, to contribute to your fellow citizens, to reduce the need for income assistance, and to build human capital. (Plus the more ephemeral goals all sides of the debate ascribe to work -- self reliance, life meaning, self-respect, participation in society, and so forth. I promised no moral or sociological arguments, but these values being shared by both sides of the debate, I can make a little exception. Nobody thinks that an entire lifetime of living on a government check, doing nothing but drink take drugs and play video games all day, makes for a desirable society, no matter who they vote for.)

If so, if the social safety net creates a 100% marginal tax rate on work, and if abandoning income phaseouts will bankrupt the state, then we have a problem.

Work requirements are an imperfect method to try to replace the incentive to work that social programs eliminate. Our government does this sort of thing all over to transfer income but contain the disincentives: Subsidize gas, and then regulate against its use for example.

It is inefficient, as you can tell from the brouhaha. It's much more efficient to get people to work by saying "if you earn a dollar, you can keep it," rather than "if you earn a dollar we'll take it away from you but we're going to force you to work." As the WSJ details here and often, the rules are complex, and people and governments game them. Just who should work? Progressives will quickly find a sick single mother taking care of elderly parents and commuting to some horrible fast food job who falls through the cracks, and they are right. Rules and bureaucracies are very rough substitutes for market incentives. More importantly, if you're working for money, you find the best job you can, you work hard, you look for better opportunities. If you're working to satisfy a bureaucratic work requirement in the face of a 100% tax rate, you find the easiest job you can, you don't care about the money and thereby the social productivity of the work, and you do as little as possible.

So I'm not defending work requirements as a perfect offset to a 100% marginal tax rate. But they are there for a reason, as a very rough offset to some of the huge disincentives that means-tested programs pose. The point today is that we should start to understand and debate work requirements in this framework. If you're going to remove market incentives, you need some replacement.

By the way, supposedly socialist Europe, after its experience with "the dole" in the early 1990s, is much more heard-hearted about these sorts of incentives than we are. Progressives who think we should both emulate nordic countries and also expand our safety net should go look at nordic countries.

Is there a better way? I've long played with the idea of limiting help by time rather than by income. That's how unemployment insurance works. We understand that replacing people's paycheck forever if they lose their job has bad incentive effects. Unemployment is understood as a temporary misfortune, and understanding the incentives, you get unemployment checks for a limited amount of time. Could not many other programs aimed at misfortune also be limited by time -- but then allow you to keep each extra dollar of earnings? Perhaps even unemployment should be a fixed amount of time, and you can keep receiving it for the full (normally) 26 weeks even if you get a job.

The trouble with that, of course, is that some people will not get their acts together in the required time, and then you have to be heartless. But is it not just as heartless to say to a person who had been on food stamps, earned income tax credit, social security disability and housing voucher, "well, congrats on getting a job, and a good one, that pays $60,000 per year. Now we're taking away all your benefits. Enjoy the $1?"

Also, the safety net does include a detailed bureaucracy to determine who is needy. Disability, unemployment, and so forth look hard at these issues. Replicating that with a different set of rules for each program seems mighty wasteful.

Another wild idea: Good economists all understand that consumption, not income, is the right measure of well being. That's why consumption taxes are a good idea, and we should measure consumption diversity not income diversity. (I don't use the word "inequality" anymore as it prejudices the right answer.) One advantage of a consumption tax is that it would be easier to condition benefits on consumption rather than income. If you work and save the results, you can keep your benefits.

One last point, which maybe should be the first point. It is a bit scandalous that income phase outs in social programs take away benefits based on market income, but not social program income. If you have food stamps and earn an extra $10,000 of income, you can lose your foods stamps. If you get housing worth $10,000, you don't lose anything. Ditto in the entire social program system. This is an immense distortion towards putting effort into obtaining more social programs rather than working. Phasing out based on consumption, including cash and non cash benefits, would make a lot more sense. But one could phase out benefits based on which other benefits you receive too. Disincentives come from the social program and tax system overall, and any hope of continuing disincentives and saving money must take a similar integrated system approach.

The argument also is over how much money the programs cost. That leads to "how could you be so heartless" vs. "but the country will go broke," also going nowhere. A focus on incentives offers the way out. Fix the incentives, and we end up helping people who need it a lot better, we end up with a lot fewer people who need help, and spend a lot less money. Win win win.

There is no clean answer. A main lesson of economics is that there is always a tradeoff between help and disincentives, between insurance and moral hazard. We can make this tradeoff a lot more efficient than it is, but we can't totally eliminate the tradeoff.

The bottom line remains, this discussion would be a lot more productive discussion if we talked about the constraint posed by incentives, rather than the usual moral mudslinging."

Friday, May 26, 2023

Let’s get this huge ‘hidden tax’ of regulation out into the open

"Smack dab in the middle of contentious debt limit negotiations, the House Budget Committee held another in its series of hearings on American economic growth, this one titled “Removing the Burdens of Government Overreach.” I had the opportunity to testify and make CEI’s case for sweeping regulatory liberalization. The following is a lightly edited version of what I had to say.

—–

When it comes to headline news, federal spending gets all the attention. That’s unfortunate, because the “hidden tax” of regulation is equally important. The Code of Federal Regulations is 188,000 pages and counting.

Regulations affect nearly every aspect of our lives, from the houses we live in to the food we eat to what we do at work. Recent proposed White House changes in an already opaque rulemaking process threaten to make regulation even less transparent.

For example, Members of the Committee may be unaware that there has been no formal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Report to Congress on regulatory costs and benefits since 2020, covering fiscal year 2019.

Only a relative handful of regulations receive rigorous analysis. Independent agencies, ascendant in President Joe Biden’s “whole-of-government” progressive pursuits like “climate crisis,” “equity” and “competition policy,” get little OMB scrutiny. Nor do the thousands of guidance documents, memoranda, circulars, notices and other decrees we refer to as regulatory dark matter.

The bottom line is that the federal government does not have any justification for its claims of net-benefits for the entire regulatory enterprise, especially since unmeasured categories of intervention such as antitrust propel cost as well.

At Biden’s direction, OMB is reformatting central regulatory review procedures through a rewrite of so-called “Circular A-4” guidance on regulatory analysis. This is problematic given the progressive transformations and federal consolidations underway in the United States.

When government steers cross-sectorally as it does today while the market merely rows—especially in the wake of the Inflation Reduction Act and other recent control-oriented spending bills—it creates compounding costs of intervention even if no specific notice-and-comment rules get issued.

Comprehensive regulatory reform is important. Congress, as the Republican Study Committee’s “GEAR” (Government Efficiency, Accountability, and Reform) task force correctly noted, has vastly over-delegated lawmaking to agencies. While Congress tends to pass from a few dozen to a couple hundred laws each year, agencies issue over 3,000 rules. So it’s a good thing that the REINS Act to require congressional approval of certain hefty rules appears in the debt limit deal proposed by the House GOP.

Fortunately, there is an appetite in the 118th Congress for reforms, and we do periodically see bipartisan appeals for transparency and better disclosure of regulatory burdens. Some might not realize that the 118th Congress’s Regulatory Accountability Act, the Guidance Out of Darkness Act, a Regulatory Improvement Commission and even regulatory budgeting boast bipartisan pedigrees. I discuss these and more in my written testimony.

Speaking of regulatory budgeting, Representative Bob Good’s “Article I Regulatory Budget Act” would make Washington’s presence in the economy more explicit by capping what agencies individually and collectively compel the private sector to spend on compliance.

More thorough cost analysis and more transparency are bipartisan winners. A generation ago, the Unfunded Mandates Act, the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, and shockingly enough, the Congressional Review Act—the very CRA that generates so much consternation now—passed with overwhelming bipartisan support with Nevada’s Harry Reid among those leading the charge.

Unfunded mandates reform was once so popular it was dubbed “S. 1” in the Senate. If, as I suspect is likely, a rise in mandates on lower-level governments and small business materializes, reform may again garner bipartisan appeal. It certainly enjoys constituent appeal.

That said, mere regulatory reform won’t suffice if Congress continues enacting legislation like that of recent years. A series of transformations are fusing the spending and regulatory state into a colossus, much of it pushed by the federal government’s extraordinary procurement and contracting power.

Overdoing regulation will derail our post-pandemic march into an era of renewed prosperity. When it comes to healthy and prolonged economic expansion, you don’t need to tell the grass to grow, but you do have to take the rocks off of it."

Have the middle class and thriving towns across America been hollowed out for decades as good‐paying jobs moved overseas and factories at home closed down?

See It’s World Trade Week…and (Apparently) the Start of the “Silly Season” in Washington by Scott Lincicome and Alfredo Carrillo Obregon of Cato.

"It’s a well‐known fact in the nation’s capital that politicians’ rhetoric gets progressively detached from reality as a November election approaches. During a race’s final few months, inconvenient things like “facts” and “logic” tend to get thrown out the window as candidates get desperate for votes.

On trade, at least, it seems President Biden has kicked off the 2024 “silly season” more than a year early.

In particular, Biden’s recent proclamation announcing World Trade Week 2023 (and implicitly justifying his tariff‐ and subsidy‐heavy “worker‐centric” trade policy) stated that, “For decades, the middle class and thriving towns across America were hollowed out as good‐paying jobs moved overseas and factories at home closed down.” Were this claim in the middle of an early‐autumn stump speech—from Biden or former President Trump—we may have given it a pass. But since the claim comes in the middle of a World Trade Week proclamation from the sitting president of the United States, we feel compelled to correct the record.

First, the only “hollowing out” of the American middle class over the last few decades has been due to U.S. households moving up the income ladder, not down. For example, Census Bureau data show that between 1990 and 2019—the era of “peak globalization”—the share of middle‐ and low‐income U.S. households (adjusted for inflation) have both declined, while the share of U.S. households annually earning $100,000 has increased (see Figure 1). Research on individuals’ wages shows much of the same thing.

Wage and income gains have been solid for lower‐income Americans over this same period. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, finds a 55 percent increase in the inflation‐adjusted incomes of U.S. households in the bottom 20 percent. These improvements would be even larger after accounting for taxes and transfers. (As noted in the introduction of the new Cato Institute book, Empowering the New American Worker, household income gains are likely not owed to a substantial increase in two‐earner families since 1990.) According to the most recent calculations from economist Michael Strain, moreover, inflation‐adjusted wages increased between 1990 and 2022 by 50, 48, 38, and 39 percent at the 10th, 20th, 30th, and 50th (median) percentiles, respectively (see Figure 2).

Second, while it is undeniably true that the United States has fewer manufacturing workers today than in the 1970s or 1980s and that most jobs (even male‐dominated, blue‐collar ones) are in services, American industrial jobs have not all been “shipped overseas.” As explained in a 2022 Cato paper, globalization undoubtedly eliminated some U.S. manufacturing jobs, especially labor‐intensive, low‐wage industries like textiles/apparel and furniture, but the main, long‐term drivers of U.S. manufacturing job‐losses are productivity gains and a shift in U.S. consumption from goods to services. Thus, countries around the world—including ones with large and persistent trade surpluses and active industrial and labor policies—have experienced their own, if not larger, declines in manufacturing jobs, and recent increases in U.S. manufacturing jobs have been accompanied by stagnating U.S. manufacturing productivity.

Furthermore, as explained in Empowering, there are still manufacturing jobs available in the United States—for those who want and can qualify for them:

Contrary to the conventional wisdom…, the current U.S. manufacturing job situation is not due to a lack of demand for these workers (caused by globalization or automation, for example): in the first quarter of 2022, there were around 850,000 unfilled manufacturing job openings, and new research from Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute estimates that this figure could hit 2.1 million by 2030.

A year later, even after a significant cooling of the U.S. manufacturing sector, job openings there are historically elevated.

Third, President Biden ignores, as we explained in a 2022 paper, the tens of millions of American jobs in services and in manufacturing that are today dependent on trade and globalization:

[A] 2020 report found that trade—imports and exports—directly or indirectly supported approximately 40.6 million jobs in both goods‐producing industries (agriculture, construction, manufacturing, etc.) or services‐producing industries (wholesale/retail trade, transportation, professional services, etc.). Imports alone support an estimated 17.3 million American jobs in transportation, logistics, wholesale and retail trade, and other services industries, which comprise more than 10 percent of total employment in the sector. And almost half of all dollars spent on imported goods go to American workers rather than to the foreigners producing the goods. Thus, new research finds that, while only 6 percent of U.S. firms in manufacturing and services are goods traders, these firms account for half of economy‐wide employment today and supported 60 percent of all new net jobs created after 2008, primarily through the establishment of new businesses. [See Figure 3.]

Meanwhile, foreign direct investment supported approximately 8 million jobs in 2019. By contrast, these same American workers are harmed by protectionism: higher input costs, for example, typically mean reduced wages or unemployment in the consuming company or industry at issue.

Surely, not every American worker has come out ahead since the United States became more integrated into the global economy, but—even leaving aside the important consumption benefits that globalization has provided all Americans (even ones who lost jobs from import competition)—the narrative of broad, trade‐driven declines in middle class jobs and lifestyles is simply false. As the Financial Times’ Martin Wolf put it in April (citing the latest academic research), “contrary to the widespread view, it is untrue that liberal trade is a dominant or even significant cause of the woes of the working classes of western societies.” Indeed.

Finally, similar conclusions may be drawn regarding American communities—including ones once dependent on manufacturing. For example, a 2018 Brookings Institution report found that 115 of the 185 countries that had a disproportionate share (20 percent or more) of manufacturing jobs in 1970 had successfully transitioned away from manufacturing by 2016. Of the remaining 70 “older industrial cities”, 40 had exhibited “strong” or “emerging” (above‐average) economic performance over the same period. Thus, by 2016 almost 85 percent of American communities once dependent on manufacturing—and thus potentially “hollowed out” by new import competition—had moved or were moving beyond their industrial past. That a handful of U.S. “mill towns” hadn’t adjusted in more than four decades reveals other (and deeper) problems than simply exposure to the modern global economy. For example:

Anecdotal evidence supports these conclusions. Former textile town Greenville, South Carolina is (along with its next door neighbor Spartanburg) today a bustling metro area with a diverse economy—including several multinational manufacturers. Just up the interstate, Hickory, North Carolina—a former textile and furniture hub that was the poster‐child for the persistent ravages of the so‐called “China Shock”—has just been named by U.S. News and World Report as the “best affordable place to live in the United States” for 2023–24. (Speaking of the China Shock, the authors of those influential studies have since acknowledged that, once you consider the substantial consumer gains from China trade, just 82 of 722 U.S. commuting zones, representing 6.3 percent of the U.S. population, would experience net welfare losses. Other scholars, of course, challenge the China Shock approach and conclusions more broadly.)

For Hickory, the USNWR highlights that manufacturing continues to account for most of the area’s jobs, yet “the industry is [now] diversified, with plastics, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals playing a bigger role.” Moreover, Google and Apple have established data centers in the area, and service‐sector businesses are growing. Recognizing the area’s potential, Appalachian State University will open a Hickory‐based campus this August.

Coming in second on the same USNWR list is former steel town Youngstown, Ohio, which is “in the midst of a cultural and economic renaissance” driven mainly by service‐sector businesses.

So much for being “hollowed out.”

None of this means, of course, that certain American communities and workers don’t face real challenges in today’s globalized world. But alleging that trade caused these ills not only ignores the gains that the vast majority of Americans have experienced since the United States opened to the world decades ago, but also distracts from—as Empowering details—“the panoply of federal, state, and local policies that distort markets and thereby raise the cost of health care, childcare, housing, and other necessities; lower workers’ total compensation; inhibit their employment, personal improvement, and mobility; and deny them the lives and careers that they actually want (as opposed to the ones DC policymakers think they should want).”

Blaming trade for these and other policies’ failures might make for a good campaign soundbite, but that doesn’t make it any less silly — especially during World Trade Week."