"Using individual tax returns, Piketty and Saez (2003) concluded that the top one percent income share at least doubled since 1960. But these estimates are biased by tax base changes, missing income sources, and major social changes. Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2018) addressed some of these issues by targeting the distribution of total national income. They concluded that the top one percent share increased by two-thirds since 1960 and doubled since 1980. However, broadening income beyond that reported on tax returns requires specific assumptions to distribute these additional income sources. This paper shows the effects of adjusting for technical tax issues and the sensitivity to alternative assumptions for distributing missing income sources. Our results suggest that recent top income shares are significantly lower and that there has been relatively little change since 1960, though a modest increase since 1980. The most important reason our results differ from Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2018) is our allocation of underreported income according to detailed IRS audit studies rather than proportional to income reported on tax returns.

Our estimates show that despite a decrease in the top federal individual income tax rate from 91 to 39.6 percent between 1960 and 2015, base-broadening reforms and the decreased use of tax shelters caused effective tax rates of the top one percent to increase from 14 to 24 percent. Considering all taxes, effective tax rates of the top one percent increased while those of the bottom 90 percent fell, suggesting an increase in overall tax progressivity."

Saturday, March 30, 2019

Between 1960 and 2015, base-broadening reforms and the decreased use of tax shelters caused effective tax rates of the top one percent to increase from 14 to 24 percent

See Income Inequality in the United States: Using Tax Data to Measure Long-term Trends by Gerald Auten Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Treasury Department & David Splinter Joint Committee on Taxation, U.S. Congress.

Finishing high school, working full time, waiting until age 21 to get married, and not having children outside wedlock greatly reduces poverty

By Rev. Ben Johnson, senior editor at the Acton Institute.

"Can avoiding a handful of socially harmful activities virtually guarantee someone will not live in poverty? Social scientists in the United States said they have found the secret, and a new report from Canada has found it also applies across the northern border.

The “success sequence” began with Isabel V. Sawhill and Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution, who found that meeting a few criteria greatly reduced the likelihood of a family living in poverty: finish high school, work full time, wait until age 21 to get married, and do not have children outside wedlock. Rick Santorum became fond of repeating these conditions during the 2012 presidential primaries, and they passed into broader use.

The Fraser Institute applied these tests and concluded they hold just as true in Canada. The report “The Causes of Poverty,” which was released on Tuesday, found that less than one percent of Canadians who graduated high school, worked full time, and waited until age 21 for marriage live in poverty.

Specifically, their poverty rate is 0.9 percent.

The poverty rate in a home where at least one person works full time is just 1.7 percent.

The poverty level for all Canadian families is 3.5 percent, but 12 percent of single-parent households led by females live in poverty, as do 14 percent of homes where no one works full time.

“The evidence is clear,” said Christopher A. Sarlo, its author. “There are certain societal norms that, if followed, are key to avoiding long-term poverty.”

Sarlo actually undersells his research: He tested only for those currently living in need, not for those in long-term poverty (which would be lower yet).

Sarlo does not overstate his findings. He highlights the importance of avoiding addiction and a criminal record, which Sawhill and Haskins omitted. And he acknowledges that conditions outside people’s control, such as mental or physical disability and natural disasters, create negative life outcomes. Yet the success sequence predicts human flourishing.

The Success Sequence Succeeds Again

Since its conditions are still normative, few people must deal with the consequences. Only 1.4 percent of Americans in 2007did not meet a single one of these benchmarks. But they account for 76 percent of the poor and 17 percent of the lower middle class.

The new study is yet another confirmation that work and personal responsibility pay economic, as well as spiritual, dividends. W. Bradford Wilcox and Wendy Wang found in a 2017 AEI study that 97 percent of millennials who followed the sequence “are not poor by the time they reach their prime young adult years (ages 28-34).”

Charles Murray covered this ground copiously in his Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010.

Raj Chetty has established that the proportion of single parents in a neighborhood affects the life outcomes of their neighbors. “[T]here is a strong relationship between upward mobility and measures of family stability. Areas with lower fractions of single parents have much higher rates of upward mobility,” he wrote.

“Work Does All of the Work”

Nonetheless, the theory has its critics on the Left, who blame structural barriers for persistent poverty. The left-wing Vox website is also triggered by the sequence’s implied morality:

Describing full-time work as a “norm” is slightly bizarre, as plenty of people are out of work despite wanting a job.… Treating birth timing as a norm is also strange, as it implies that people have more control over when to have children than they often do.Matt Bruening of Jacobin magazine called the success sequence “a totally ad hoc set of rules that … allow conservatives to say personal failures are the cause of poverty in society.”

Bruening said that having a full-time job accounts for virtually all the difference. “[N]one of the rules provide meaningful poverty reduction after you have applied the full-time work rule,” he wrote. (Emphasis in original.)

Put another way, he wrote, “Work does all of the work.”

But if full-time employment is the one-step path to success, then the new Jacobins should embrace the success sequence.

Sarlo noted the difference marriage makes in his new study. In the U.S., more single mothers than married mothers are working outside the home. However, more than one-in-four single mothers—and nearly one-third of single mothers with children under six—are unemployed. In a single-parent home, that means zero earned income.

Single mothers earn $20,000 a year less than the U.S. median income, often because they must seek flexible work to tend to home emergencies. There is simply less time and energy to go around when all the responsibilities fall on two, rather than four, shoulders.

Critics such as Bruening should also follow Sarlo to his next unique contribution to the success sequence: After he weighed the data, Sarlo concluded that “the existing welfare system”—or as it is called in Canada, social assistance—“turns out to be the key enabler of poverty”:

In practice, a system that has no employment strategy for clients, has no requirements of them, and expects nothing from them, is simply unhelpful. It slowly traps some people, especially those with low self-esteem and little confidence, into a child-like state of dependency and permanent low income.Welfare policies that slowly break down the work ethic should trouble critics such as Bruening, et. al., who believe full-time work is the only prerequisite to prosperity. “[B]ad choices and bad luck are not destiny,” Sarlo wrote. But “[b]ad choices can be enabled by ineffective and counterproductive policy.”"

Friday, March 29, 2019

The Federal Minimum Wage Increase Hurt Many Low-Skilled Workers

By David Henderson.

"We find that increases in the minimum wage significantly reduced the employment of low-skilled workers. By the second year following the $7.25 minimum wage’s implementation, we estimate that targeted individuals’ employment rates had fallen by 6.6 percentage points (9%) more in bound states than in unbound states. The implied elasticity of our target group’s employment with respect to the minimum wage is −1, which is large within the context of the existing literature.We next estimate the effects of binding minimum wage increases on low-skilled workers’ incomes. The 2008 SIPP [Survey of Income and Program Participation] panel provides a unique opportunity to investigate such effects, as its individual-level panel extends for 3 years following the July 2009 increase in the federal minimum wage. We find that this period’s binding minimum wage increases reduced low-skilled individuals’ average monthly incomes. Relative to low-skilled workers in unbound states, targeted individuals’ average monthly incomes fell by $90 over the first year and by an additional $50 over the following 2 years. While surprising at first glance, we show that these estimates can be straightforwardly explained through our estimated effects on employment, the likelihood of working without pay, and subsequent lost wage growth associated with lost experience. We estimate, for example, that targeted workers experienced a 5 percentage point decline in their medium-run probability of reaching earnings greater than $1500 per month.This is from Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither, “The minimum wage and the Great Recession: Evidence of effects on the employment and income trajectories of low-skilled workers,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 170, February 2019. The article is gated.

Clemens and Wither explain in the piece the difference between “bound” and “unbound” states. Bound states are states that had a minimum wage that was below $6.55 an hour on January 2008. Unbound states were states for which that was not true. The idea is that the closer the state’s minimum wage was to $7.25 before the federal minimum was raised from $5.15 to $7.25, the less binding was the law."

Lyft and the 'Cheers' IPOs: How Overregulation Leaves Middle-Class Investors Behind

By John Berlau of CEI.

"When Starbucks went public in 1992, most people outside of the chain’s home base of Seattle hadn’t heard its name. Even fewer people had heard of Home Depot when it went public on NASDAQ in 1981 as a very small chain with only four stores, all operating in Georgia.

And whereas the size of Lyft’s IPO is $2.2 billion (with a total valuation of the company at $24 billion). Starbucks’ IPO was less than $50 million. But so was that of Cisco Systems in 1990. And that of Amazon in 1997. In fact, as I said in my testimony in 2017 at a hearing held by the House Financial Services Committee: “In the early 1990s, 80 percent of companies launching IPOs—including Starbucks and Cisco Systems—raised less than $50 million each from their offerings.

Entrepreneurs were able to get capital from the public to grow their firms, while average American shareholders could grow wealthy with the small and midsize companies in which they invested.”

But all this changed dramatically after the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, a law that quadrupled auditing costs for many public companies after being rammed through Congress in the wake of the failures of Enron and Worldcom. As a result, a few years after “Sarbox” was enacted, 80 percent of firms went public with IPOs greater than $50 million, while IPOs greater than $1 billion have become a normal occurrence. This means that ordinary investors—as opposed to venture capitalists, angels, and other wealthy “accredited investors” the government allows to purchase shares in private companies—are locked out of the early-stage growth of the small companies that could become tomorrow’s giants.

Having not learned its lesson, Congress then piled on with the Dodd-Frank so-called “Wall Street Reform” Act in 2010, which pummeled public companies with mandates such as tracking use of “conflict minerals” and the “pay ratio” of highest to lowest paid employees that added substantial costs to achieve social agendas and did virtually nothing to prevent investor fraud.

Lyft’s IPO filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) showed that these mandates can put a substantial burden even on a company as big as Lyft. Citing Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, Lyft warns potential shareholders in a list of “risk factors” in its filing: “Operating as a public company requires us to incur substantial costs and requires substantial management attention … As a public company, we will incur substantial legal, accounting and other expenses that we did not incur as a private company.”

If a firm as big as Lyft considers these mandates burdensome enough to be a “risk factor” to its success, imagine what smaller companies have to deal with. That’s why Congress—short of repealing much of Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank—should immediately take up bipartisan JOBS Act 3.0 legislation that passed last Congress overwhelmingly (even with the support of Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA), which she recently reiterated).

This includes the Fostering Innovation Act, which was made part of the Jobs and Investor Confidence Act, which extended for some midsize public companies the original JOBS Act’s exemption from the Sarbanes-Oxley “internal control” mandates. Then-Rep. (and now Senator) Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ), a co-sponsor of the legislation, said in 2017 that it “allows innovative companies to spend valuable resources on product research and development instead of costly and unnecessary external audits. This commonsense solution cuts red tape and allows companies to move life-saving innovations forward.”"

Thursday, March 28, 2019

If low-priced foreign steel endangers America’s “economic security,” evidence of our economic decline would now be overwhelming

From Don Boudreaux.

"Here’s a letter to the Wall Street Journal:

Editor:

United States Steel Corp. CEO David Burritt pleads for government to protect his industry by punitively taxing American buyers of foreign-made steel (Letters, March 26). But he overplays his hand by writing that “For decades, foreign countries and their steel companies have been flooding steel imports into the U.S. at the expense of … our national economic security.”

Surely if low-priced foreign steel endangers America’s “economic security,” evidence of our economic decline would now be overwhelming given that this perilous product has allegedly been “flooding” onto our shores for decades. Yet where is such evidence?

Unemployment in the past half century seldom has been as low as it is today. U.S. industrial production hit an all-time high in November. American exports reached an all-time high last year before Pres. Trump’s trade war took its predictable toll on them. U.S. industrial capacity is now at an all-time high, as is real GDP per capita. Ditto for household net worth, which in inflation-adjusted dollars is today 70 percent higher than it was in 2001, the year when China joined the WTO, and 300 percent higher than in 1975, the last year when America ran an annual trade surplus."

Basic food items in America have become almost eight times cheaper relative to unskilled labor over the last 100 years

By Marian L. Tupy of Cato. Excerpt:

"In fact, basic food items in America have become almost eight times cheaper relative to unskilled labor over the last 100 years.

This analysis of the cost of food in America over the last century begins with Retail Prices, 1913 to December 1919: Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, No. 270, which was published in 1921. On pages 176-183, we encounter nominal prices of 42 food items – ranging from a pound of sirloin steak to a dozen oranges – as registered in the city of Detroit in 1919. Those can be seen in the second column of the attached graphic.

Our second step was to express those nominal prices in terms of hours of human labor. Together with Gale Pooley, associate professor of business management, Brigham Young University-Hawaii, we took the index of hourly wages of unskilled laborers (i.e., workers at the bottom of the income ladder) between 1774 and 2016 from www.measuringworth.com and re-indexed it to 1919. That gave us a nominal wage rate of unskilled laborers amounting to $0.25 per hour in 1919. The nominal prices of food relative to nominal wages in 1919 can be seen in column 3.Our third step was to find the nominal prices of the same goods (including, of course, the same quantity of those goods) on www.walmart.com, which is where most unskilled laborers shop in 2019. Those findings can be seen in column 4. According to our calculations, the nominal wage rate of unskilled laborers amounts to about $12.70 per hour today. As such, the nominal prices of food relative to nominal wages in 2019 can be seen in column 5.

What did we find?

- The time price (i.e. nominal price divided by nominal hourly wage) of our basket of commodities fell from 47 hours of work to ten (see the Totals line in column five).

- The unweighted average time price fell by 79 percent (see the Totals line in column six).

- Put differently, for the same amount of work that allowed an unskilled laborer to purchase one basket of the 42 commodities in 1919, he or she could buy 7.6 baskets in 2019 (see the Totals line in column seven).

- The compounded rate of “affordability” of our basket of commodities rose at 2.05 percent per year (see the Totals line in column eight).

- Put differently, an unskilled laborer saw his or her purchasing power double every 34 years (see the Totals line in column nine).

Pay particular attention to column six and note that declining prices result in exponential, not linear, gains. Thus, a 75 percent decline in price allows a person to purchase four items; a 90 percent decline results in ten items; a 95 percent decline in 20 items; and a 96 percent decline in 25 items. A 1 percentage point change from 95 percent to 96 percent, in other words, enhances the gain by 25 percent.

Thus eggs, which declined by 96 percent in terms of time price between 1919 and 2019, allow the unskilled laborer today to purchase 24 times as many eggs as an unskilled laborer was able to purchase for the same amount of work a century ago. That’s a massive improvement – even if we ignore the likelihood that an unskilled laborer today performs work that is less physically strenuous and less dangerous than it was in 1919.

Far from being irredeemable, therefore, a market that’s allowed to function relatively freely and competitively has delivered and can continue to deliver enormous benefits to all people, especially those at the bottom of the income ladder.

Joseph Schumpeter, the famous economist who served as Austrian minister of finance in 1919, observed that the “capitalist engine is first and last an engine of mass production which unavoidably also means production for the masses … It is the cheap cloth, the cheap cotton and rayon fabric, boots, motorcars and so on that are the typical achievements of capitalist production, and not as a rule improvements that would mean much to the rich man. Queen Elizabeth owned silk stockings. The capitalist achievement does not typically consist in providing more silk stockings for queens but in bringing them within reach of factory girls.”

To those silk stockings we can now add food."

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Concentration at the local level may be decreasing

From John Cochrane.

"Is the US economy getting more concentrated or less? At the aggregate level, more. This is a widely noted fact, leading quickly to calls for more active government moves to break up big companies.

But at the local level, no. Diverging Trends in National and Local Concentration by Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, Pierre-Daniel Sarte, and Nicholas Trachter documents the trend.

They make a concentration measure that is basically the sum of squared market shares, so up means more concentrated and down means less concentrated. This is the average of many different industries and markets.

The average concentration of national markets has gone up. But the concentration of smaller and smaller markets has gone down. More businesses are dividing up county and zip code markets.

Industries differ. This graph does not get a prize for ease of distinguishing the lines, but the two red lines just below zero are manufacturing and wholesale trade, where the industries with really dramatic reductions in local concentration are retail trade, finance insurance and real estate, and services.

What's going on? The natural implication is that the town once had 3 local restaurants, two local banks, and 3 stores. Now it has a McDonalds, a Burger King, a Denny's and an Applebees; a branch of Chase, B of A, and Wells Fargo, and a Walmart, Target, Best Buy, and Costco. National brands replace local stores, increasing the number of local stores.

However, that turns out not to be so obvious.

This graph shows what happens in the diverging industries (those in which national goes up, and local goes down) if you leave out the biggest company. Doing so, lowers the rise of national concentration, because we left out the single most concentrated firm. The lower line however, shows a positive effect. If we leave out the largest national firm, the local markets look more concentrated. If national brands had just replaced local businesses, then when we leave them out, we should see lots of smaller shares. The same thing happens if we leave out the second and third largest.

What's going on? Well, they look at what happens when Wal-Mart comes to town.

The lower line is the effect on concentration in the years before and after the top national firm enters a market. Concentration drops. If, when Wal-Mart came to town, all the exiting firms went under, concentration would rise. The upper line shows you concentration ignoring the largest enterprise. It's unchanged. Either the mom and pop stores do, in fact, stay in business; or new smaller firms enter along with Wal-Mart. The phenomenon is not just the replacement of all smaller businesses by a larger number of national chains.

The paper was presented at the San Francisco Fed "Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy" conference, where I am today. The discussions, by Huiyu Li and François Gourio, were excellent. As with all micro data there is a lot to quibble with. Is a zip code really a market? Much of the data are industry+zip codes with a single firm, both before and (slightly less often) after. Maybe Walmart and other stores drag in customers from other places? And of course, concentration is not the same thing as competition. The SF Fed will, in a week or so, post the conference, papers, and discussions."

Research finds US shale revolution is responsible for saving tens of thousands of lives every year

From Mark Perry.

"Here’s the abstract of the March 2019 NBER paper “Inexpensive Heating Reduces Winter Mortality“:

This paper examines how the price of home heating affects mortality in the US. Exposure to cold is one reason that mortality peaks in winter, and a higher heating price increases exposure to cold by reducing heating use. It also raises energy bills, which could affect health by decreasing other health-promoting spending. Our empirical approach combines spatial variation in the energy source used for home heating and temporal variation in the national prices of natural gas versus electricity. We find that a lower heating price reduces winter mortality, driven mostly by cardiovascular and respiratory causes.And here’s the conclusion (emphasis added):

This paper finds that winter mortality is lower when the price of heating is lower. To put the estimated elasticity of all-cause mortality with respect to the price of heating of 0.03 in context, the price of natural gas relative to electricity fell by 42% between 2005 to 2010. Our findings imply that this price decline caused a 1.6% decrease in the winter mortality rate for households using natural gas for heating. Given that 58% of American households use natural gas for heating, the drop in natural gas prices lowered the US winter mortality rate by 0.9%, or, equivalently, the annual mortality rate by 0.4%. This represents more than 11,000 deaths per year.Bottom Line: The American shale gas revolution illustrated above by the 57% increase in natural gas production in the US since 2006, which contributed to a 53% decrease in natural gas prices has helped to save tens of thousands of deaths every year. Likewise, any increase in average winter temperatures would similarly reduce winter mortality in the US and around the world. In contrast, how many lives would be lost if the Green New Deal was implemented and energy prices from inefficient windwills and solar panels dramatically increased?

This effect size is large enough that it should not be ignored when assessing the net health effects of shale production of natural gas. The findings also highlight the health benefits of other policies to reduce home energy costs, particularly for low-income households.

According to The Economist “Few businesspeople have done as much to change the world as George Mitchell,” the father of fracking who pioneered the economic extraction of shale gas. George Mitchell died in 2013, but if he were still alive I would nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize for changing the world and saving tens of thousands of lives from lower energy costs. The Father of Fracking has saved infinitely more lives that past Nobel Peace laureates like Jimmy Carter, Barack Obama and Al Gore."

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

Yellen Says She’s ‘Not a Fan of MMT’ as List of Detractors Grows

By Enda Curran of Bloomberg.

"Former Federal Reserve chief Janet Yellen said she’s not a fan of modern monetary theory, saying its proponents are “confused” about what can fuel inflation in the economy.

Yellen took issue with those promoting MMT who suggest “you don’t have to worry about interest-rate payments because the central bank can buy the debt,” she said at an Asian investors’ conference hosted by Credit Suisse in Hong Kong. “That’s a very wrong-minded theory because that’s how you get hyper-inflation.”

The former Fed chair said she was “not a fan” when asked about the decades-old theory, which has gained recent traction in the U.S. particularly amid a run-up in government debt. Yellen joins a list of well-known names such as billionaire investor Warren Buffett and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers who have said they’re opposed to the theory."

"Former Federal Reserve chief Janet Yellen said she’s not a fan of modern monetary theory, saying its proponents are “confused” about what can fuel inflation in the economy.

The former Fed chair said she was “not a fan” when asked about the decades-old theory, which has gained recent traction in the U.S. particularly amid a run-up in government debt. Yellen joins a list of well-known names such as billionaire investor Warren Buffett and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers who have said they’re opposed to the theory."

Is There a Green Rational Deal?

Congressional Democrats propose a fantastically expensive plan to fix precisely nothing.

By Holman W. Jenkins, Jr. Excerpts:

By Holman W. Jenkins, Jr. Excerpts:

"the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the accepted authority, has failed to improve upon a 40-year-old guesstimate that a doubling of atmospheric CO2 would lift global temperature somewhere between 2.7 and 8.1 degrees Fahrenheit.

The IPCC does not claim this wide and baggy range is even reliable, only that it comports with a variety of computer simulations."

"If the world adopts the widely prescribed goal of holding temperature increase to 3.6 degrees above the preindustrial average, it might require forestalling 300 billion tons of future emissions—or perhaps 900 billion tons.

We might spend $2 trillion a year and avoid 6.3 degrees of additional warming—or maybe only 0.9 degrees."

"Government scientists, without being especially upfront about it, combined extreme worst-case assumptions both for future emissions and for how much warming might result from a given amount of emissions.

They came up with a shocking forecast of a U.S. temperature increase of 11 degrees Fahrenheit by 2090. Even so, their estimate of the annual damage to the U.S. economy was a manageable $500 billion, or about 0.8% of national income assuming a meager 1.6% annual growth rate between now and then."

As Costs Skyrocket, More U.S. Cities Stop Recycling

With China no longer accepting used plastic and paper, communities are facing steep collection bills, forcing them to end their programs or burn or bury more waste.

By Michael Corkery of The NY Times. Excerpts:

By Michael Corkery of The NY Times. Excerpts:

"Philadelphia is now burning about half of its 1.5 million residents’ recycling material in an incinerator that converts waste to energy. In Memphis, the international airport still has recycling bins around the terminals, but every collected can, bottle and newspaper is sent to a landfill. And last month, officials in the central Florida city of Deltona faced the reality that, despite their best efforts to recycle, their curbside program was not working and suspended it.Those are just three of the hundreds of towns and cities across the country that have canceled recycling programs, limited the types of material they accepted or agreed to huge price increases.""China, which until January 2018 had been a big buyer of recyclable material collected in the United States. That stopped when Chinese officials determined that too much trash was mixed in with recyclable materials like cardboard and certain plastics.""recycling companies are . . . charging cities more, in some cases four times what they charged last year.""many waste companies had historically viewed recycling as a “loss leader,” offering the service largely to win over a municipality’s garbage business.""While there remains a viable market in the United States for scrap like soda bottles and cardboard, it is not large enough to soak up all of the plastics and paper that Americans try to recycle. The recycling companies say they cannot depend on selling used plastic and paper at prices that cover their processing costs"

Monday, March 25, 2019

How Are Those Steel Tariffs Working?

WSJ editorial. Excerpt:

• Trade deficit. “We need and we will get lower trade deficits, and we will stop exporting jobs and start exporting more products instead,” Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said last March after the President announced his steel tariffs. We disagree with the President’s preoccupation with trade deficits, which are affected more by capital flows and currency values than trade policy.

But it’s worth pointing out that the trade deficit in steel increased last year by $1 billion as exports (measured in dollars) fell 7% and imports rose 1%. Imports ton for ton fell more than exports did. But the average price of steel per ton increased more for imports than exports, perhaps due to shifts in currency values and product deliveries—e.g., businesses importing more expensive specialized steel grades.

Retaliatory tariffs by Canada and Mexico contributed to a $650 million drop in American steel exports. At the same time imports increased from Mexico and Canada, which are deeply integrated into U.S. supply chains. In many cases manufacturers paid the tariff and passed on the cost to customers.

Mr. Trump’s tariffs had a de minimis impact on Chinese imports, which were already subject to 28 dumping duties. They principally reduced imports from Turkey, Russia and South Korea, which turned around and shipped more steel to other countries.

For example, U.S. imports from Turkey fell by 930,000 tons last year. But Turkey exported 330,000 more tons to Canada and 780,000 more tons to Italy. European steel makers have complained that a flood of imports is driving down prices. But lower prices have made European manufacturers more competitive. Some U.S.-based manufacturers like Harley-Davidson have also moved production overseas to dodge retaliatory tariffs and take advantage of lower steel prices.

• Jobs. While domestic steel production rose 5% last year, the tariffs had little impact on employment in the industry. Steel makers added 2,200 jobs in 2017, but just 200 in the last year. One reason is that steel makers ramped up production at highly-efficient minimills with electric-arc furnaces that employ few workers."

Banishing Profit Is Bad for Your Health

The Medicare for All proposal from House Democrats follows New York state’s bad example

By Bill Hammond. He is director of health policy at the Empire Center. Excerpts:

By Bill Hammond. He is director of health policy at the Empire Center. Excerpts:

"The Empire State’s hospital industry has been 100% nonprofit or government-owned for more than a decade. It’s a byproduct of longstanding, unusually restrictive ownership laws that squeeze for-profit general hospitals. The last one in the state closed its doors in 2008.

A report last year from the Albany-based Empire Center shows the unhappy results. The state health-care industry’s financial condition is chronically weak, with the second-worst operating margins and highest debt loads in the country. And there’s no evidence that expunging profit has reduced costs. New York’s per capita hospital spending is 18% higher than the national average.

The overall quality of New York’s hospitals, even factoring in Manhattan’s flagship institutions, is poor. Their average score on the federal government’s Hospital Compare report card was 2.18 stars out of five—last out of 50 states. Their collective safety grades from the Leapfrog Group and Consumer Reports magazine have also been dismal.

The state’s nonprofit hospitals also fall short on accessibility for the uninsured. On average they devoted 1.9% of revenues to charity care in 2015, a third less than privately owned hospitals nationwide.

Finally, New York’s antiprofit policy doesn’t even prevent people from getting rich. Seven-figure salaries are common among the state’s hospital executives. If banning profit is an effective way to improve health-care, there’s no evidence to be found in New York.

Not content to destroy the profit system for health-care providers, sponsors of the House Medicare for All bill would also blow up the patent system for prescription drugs. If a manufacturer won’t agree to an “appropriate” price for its product, federal officials could abrogate the patent and assign another company to make the drug. The original patent holder would receive “reasonable” compensation for its losses, but only after the government discounts costs as it sees fit. Knowing that patents could be overridden at anytime, the private sector would have far less incentive to invest billions to find medical breakthroughs, slowing progress against disease and disability."

Sunday, March 24, 2019

The War on Poverty Remains a Stalemate

Education gaps between socioeconomic classes haven’t narrowed in the past half-century

By Eric A. Hanushek and Paul E. Peterson. Excerpt:

By Eric A. Hanushek and Paul E. Peterson. Excerpt:

"Since 1980 the federal government has spent almost $500 billion (in 2017 dollars) on compensatory education and another $250 billion on Head Start programs for low-income preschoolers. Forty-five states, acting under court orders, threats or settlements, have directed money specifically to their neediest districts. How much have these efforts helped?

To find out, we tracked achievement gaps between those born into families with the highest and lowest levels of education and household resources. We looked at both the gap between the top and bottom tenths of the socioeconomic distribution (the 90-10 gap) and the top and bottom quarters (the 75-25 gap).

Our finding, published by EducationNext, is that the gaps have not narrowed over the past 50 years, despite all the money spent on that objective. In 1971, shortly after the launch of the War on Poverty, 14-year-olds in the bottom decile trailed those in the top decile by three to four years worth of school. For those who were born in 2001 and turned 14 in 2015, the gap was still three to four years. Similarly, the 75-25 gap has remained wide—between 2½ and three years.

We examined 98 separate assessments of student achievement in math, reading and science, administered to adolescents born between 1954 and 2001 by the U.S. government and trustworthy international agencies. The surveys also collected information on parents’ educational attainment and the material possessions in the home, thereby supplying information needed to ascertain the students’ socioeconomic backgrounds. Surprisingly, we were the first to use this valuable storehouse of information to examine the success of the war on poverty.

The persistence of the 90-10 and 75-25 gaps is not caused by changes in schools’ ethnic composition. It is true that the white share of the school-age population has fallen, from 75% to 54%, but the gaps are as sustained for white students as they are for the school-age population as a whole. The black-white test-score gap did narrow, but that progress halted during the past quarter-century.

It wouldn’t be so bad if a rising tide were lifting all boats—that is, if haves and have-nots alike were reaching new levels of accomplishment, despite persistent gaps. But the past quarter-century has seen no gains in overall student performance at 17. Gains observed at 14 dissipate by the time students reach the last year of high school and are expected to enter the workforce or college."

The Trouble With Taxing Wealth

Elizabeth Warren’s proposed tax on net worth seems like a nearly surgical strike at inequality, but it may not be efficient

By Greg Ip. Excerpt:

By Greg Ip. Excerpt:

"Denmark abolished its wealth tax, borne by the wealthiest 2% of families, between 1989 and 1997. In the subsequent eight years, the wealthiest families’ net worth rose 30%, according to a study by Katrine Jakobsen and three co-authors distributed last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The authors attribute most of this to increased saving.

Alan Auerbach, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, thinks this shows a U.S. wealth tax would reduce wealth and saving by enough to hurt investment and economic growth. This might be offset if the U.S. turns to foreign savings to finance an investment. This, however, means foreigners would take a bigger share of U.S. income."

Saturday, March 23, 2019

Normalizing Trade Relations With China Was the Right Thing To Do

By Daniel Griswold of Cato. Excerpt:

"Congress passed PNTR to smooth China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), but the country probably would have joined the WTO either way. And Congress would likely have continued renewing normal trade relations with China each year, as it had since 1980, granting it the same access to the U.S. market as almost all our other trading partners. The key difference would have been that the United States would not have benefited from the Protocol of Accession that China had signed, in which it made significant commitments to reduce tariffs and to further open its economy to imports and investment. Other WTO members would have gained that additional market access, while U.S. producers would have faced higher, discriminatory barriers.

Rejecting PNTR would also have meant that the U.S. could not use the WTO dispute settlement mechanism to challenge Chinese trade practices. A recent analysis by the Cato Institute documents 22 cases brought by the United States against China since it joined the WTO in 2001. "In all 22 completed cases, with one exception where a complaint was not pursued, China's response was to take some action to move toward greater market access," Cato concluded, adding that "there are no cases where China simply ignored rulings against it."

By approving PNTR, the U.S. Congress opened the door for U.S. producers to dramatically expand the value of American-branded goods and services sold in China. Under China's accession agreement, its average duty applied to products the U.S. exports to China has dropped from 25 percent before its entry to 7 percent. It has also liberalized its rules on services trade and foreign direct investment.

As a result, U.S. exports of goods and services to China have grown exponentially, according to Commerce Department figures. From 2001 through 2017, before the Trump administration launched its current trade war against China, annual U.S. exports grew from $24.5 billion to $187.5 billion, an almost eightfold increase. Sales by U.S. majority-owned affiliates in China soared more than tenfold from 2001 to 2016, from $32.6 billion to $345.3 billion; profits from those operations grew more than fourteenfold, from $1.8 billion to $26.0 billion. Between exports and affiliate sales, U.S. companies now sell half a trillion dollars of goods and services a year in China.

To show the supposed failure of past trade policy, Lighthizer held up a chart at the Ways and Means hearing showing that the U.S. bilateral goods deficit with China has grown since 2001. But almost all economists agree that bilateral deficits are virtually meaningless; they certainly are not a scorecard on the benefits of a trade relationship. At any rate, a major reason why our deficit with China has grown is that goods we used to import directly from other East Asian nations, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, are now routed through China for final assembly before being shipped to the United States. If we take into account only the value added in China, the bilateral deficit shrinks by more than one third.

When Lighthizer flashed his graph, he should have been asked why the deficit with China has kept climbing under the Trump administration's new get-tough policy. The merchandise trade deficit with China in 2018 was a record $419 billion, a full 20 percent higher than the 2016 deficit before the administration came into office. Far from "fixing" the deficit with China, the administration's policies have been accompanied by a rise in imports from China and a fall in U.S. exports.

The administration is not responsible for the growing deficit, but the fact that it has grown despite the duties levied on $250 billion of imports from China buttresses the argument that deficits are the result of underlying macroeconomic forces and are not easily changed by adjusting tariffs.

Lighthizer raised another familiar piece of evidence when he invoked the loss of manufacturing jobs. "In 2000, the year before China joined the WTO, there were 17.3 million manufacturing jobs in the United States," he told the committee. "By 2016, 5 million of those jobs were lost." He acknowledged that not all those jobs were lost because of China, but he left open just how many.

The truth is that more than 80 percent of those jobs disappeared not because of trade with China, or trade with any country, but because of automation and productivity gains. Even the much-cited "China Shock" study by economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson estimated that China trade was responsible for just under 1 million net manufacturing jobs lost during that period.

Many of those jobs probably would have been lost anyway, regardless of whether China got PNTR status or joined the WTO, thanks to expiring global quotas on the textile and apparel trade and to China's ongoing growth as an export platform. And the direct connection between imports and manufacturing jobs is shaky. In the past two years, a thriving U.S. manufacturing sector has actually added a net 458,000 jobs, all while imports from China and the rest of the world continued to rise.

The fact that China has failed to evolve into a free-market democracy since 2000 is not a failure of trade liberalization or the WTO. The WTO was not created to transform the political and economic systems of its members. It was created to advance the more modest goals of establishing and enforcing basic rules for global trade while facilitating agreements to reduce trade barriers worldwide. And it has done that. Far from being a mistake, that 2000 vote brought China under the discipline of more WTO rules and further opened the growing Chinese market to U.S. goods and services. Far from being a mistake, the vote in 2000 on China PNTR was one of the finer moments of bipartisan postwar trade policy."

Brazil's Trade War Is a Warning to America

Brasilia’s sad experience should teach Washington that protectionism does not lead to prosperity.

By Donald Boudreaux & Hane Crevelari. Donald J. Boudreaux is a senior fellow with the Mercatus Center and a professor of economics at George Mason University. Hane Crevelari , a native of Brazil, is a Mercatus MA fellow.

Excerpt:

By Donald Boudreaux & Hane Crevelari. Donald J. Boudreaux is a senior fellow with the Mercatus Center and a professor of economics at George Mason University. Hane Crevelari , a native of Brazil, is a Mercatus MA fellow.

Excerpt:

"In terms of international trade, Brazil has an average applied tariff rate of 8.59 percent on imports, much higher than the world average of 2.59 percent . Its highest bound tariff rates are on agricultural and industrial products. Those rates sit at about 55 and 35 percent , and they stifle economic competition and prompt producers to raise prices accordingly. Brazilian consumers shelled out the equivalent of an extra (and unnecessary) $35.13 billion in 2015.

Protectionist measures, such as tariffs and quotas, partially explain why buying an iPhone X in Brazil costs more than flying from Rio de Janeiro to Miami, purchasing the phone there, and then flying back to Brazil.

Protectionism also negatively affects many producers, both domestic and foreign. The Brazilian government frequently adjusts tariff rates “to protect domestic industry from import competition and to manage prices and supply,” creating an environment for producers that is both bureaucratic and unpredictable.

First, foreign companies are either scared away or forced to manufacture locally to overcome trade barriers (and despite what protectionists say, forcing companies to manufacture locally does not necessarily lead to long-run job creation).

Second, less foreign competition suppresses domestic innovation, which in turn lowers the incentives for leading domestic firms to take their products abroad. As Brazilian firms become less competitive in the global market, they become more dependent for their survival on protectionist measures. In fact, a reduction in Brazil’s trade barriers “ would increase its integration into the world economy” by expanding production and jobs in the manufacturing sector, increasing economic efficiency, lowering prices, and boosting international competitiveness, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

It’s likely no coincidence that Norway—with a mere 2.5 percent of Brazil’s population—had roughly the same number of exporting companies (just under twenty thousand) in 2013. Norway’s market is mostly open, with “more than 95 percent of industrial tariff lines [being] currently duty free,” according to the United States Trade Representative. Norway’s average applied tariff rate is only 3.4 percent .

Reversing protectionist policies is politically difficult, however, and Bolsonaro is already facing pressure from special-interest groups that do not want to lose the special status they’ve enjoyed under previous governments.

One recent example is the Brazilian dairy industry. Since 2001, Brazilian consumers have faced 14.8 percent and 3.9 percent tariffs on European and New Zealand milk. Citing a lack of evidence to support the tariff, the Ministry of the Economy took steps to extinguish it. But local milk producers balked, and the president succumbed to the pressure.

In order to reimplement the tariffs without violating World Trade Organization rules, Brazilian officials had to find a loophole. They first considered raising the South American trade bloc Mercosur’s Common External Tariff from 28 percent to 42.8 percent to maintain Brazil’s previous tariff levels. However, negotiating higher tariffs with the bloc’s other members has proved difficult. Now, Brazil is considering reimposing the tariffs as a form of retaliation against the EU’s latest duties on steel, which is permitted under WTO rules."

Friday, March 22, 2019

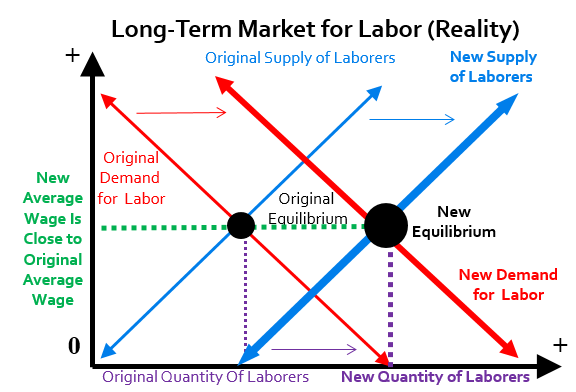

Immigrants Don’t Depress Wages

Those who cite classical economics to discredit “open borders” forget Say’s Law and half of Supply-and-Demand

By Stuart Hayashi of Arc Digital. Excerpt:

By Stuart Hayashi of Arc Digital. Excerpt:

"These pundits overlook two important considerations.

First, when foreign-born laborers get off from work for the day, do they not take the money they earned and exchange it for products they need? Foreign-born workers need food and other amenities, which they procure from businesses. As they serve a growing number of foreign-born customers, these businesses notice they are understaffed. The businesses’ drive to meet the foreign-born workers’ demand for their wares, in turn, raises these businesses’ demand for employees, bidding wages upward. Texas Tech University’s Benjamin Powell (1, 2) and the Cato Institute’s Alex Nowrasteh corroborate this interpretation.

A case study: despite Trump’s recent fretting over a caravan of 7,000 Honduran asylum-seekers, that is less than one-tenth as many people as the 125,000 Cuban refugees who arrived in Miami on rickety boats between April and October 1980. This mass migration expanded the city workforce’s overall size by 7 percent, with the size of the unskilled workforce growing by one-fifth. When economist David Card looked into the long-term consequences, he found no decrease in Miami’s employment levels or wages.

If real wages descended for the long term, workers would see no real gains. But they do. Mexicans came to the U.S. between 1941 and 1964 for agricultural jobs, and their children and grandchildren moved into more-skilled employment, some coming to own their own vineyards. This is comparable to how workers who toiled in Mattel’s toy factories in Taiwan in the 1970s ascended to First-World affluence within three decades.

Second, immigration skeptics characterize U.S. firms’ preference for hiring foreign-born workers as some initiative to cut costs. Yet most of the cost-cutting that has displaced traditional forms of native-born employment comes not from the hiring of foreign-born workers but from innovations in automation that produce more units of output with ever-smaller and ever-fewer inputs of labor and natural resources. Whatever the main factor in cutting costs, it is not as if domestic firms make no use of the money they save. They re-invest the cost savings into new operations, which benefits native-born workers through two paths: new operations are staffed by new hires, and, when the savings are invested in efficiency-improving technologies, native-born workers put in fewer hours of work than their parents did to produce and purchase the very same goods. Thus, as the U.S. industrialized between 1860 and 1890, its foreign-born population rose from 4.1 to 9.2 million, while its manufacturing workers experienced a 50 percent gain in real wages.

As Örn Bodvarsson and colleagues observe, this is a principle explained by a classical economist whom Thomas Jefferson praised as greater than Adam Smith: Jean-Baptiste Say. It is Say’s Law of Markets.

To have demand for a commodity is not merely to desire it, but to be both willing and able to exchange something for it. You only have demand for anything once you possess a supply of something that is of value to others — such as your capacity to perform jobs for others. Say articulates:

We do not in reality buy the objects we consume with money or circulating coin which we pay for them. We must in the first place have bought this money itself by the sale of productions of our own.

Your devotion of time at work is what you trade in exchange for products that other workers were hired to craft.

Because money is but a tool for facilitating the trade of one set of goods for another, all money gets traded away in the long run. This is one reason why firms re-invest the money saved from their cost-cutting. Hence, Say phrases his Law thusly:

As soon as [foreign-born workers] are provided with the means of producing [jobs being such means], they appropriate their productions to their wants; ...we [workers] offer (or supply) productive means, and demand in return the thing of which we feel the greatest want (emphases Say’s).

As every dollar earned will inevitably be spent, demand is ultimately the mirror image of supply. And the quantity by which foreign-born people increase the supply of productive labor is also an increase in demand for still more productive work, including the work of native-born citizens.

Regrettably, even the center-left’s ostensive “defenses” of immigration against conservatives decidedly snub Say’s Law. Writing in The Washington Post “Wonkblog,” Mike Konczal denies that immigrants adversely affect native-born citizens, but mostly because, Konczal maintains, the jobs for which unskilled immigrants compete are not the same jobs that native-born citizens covet.

Through similar reasoning, Sargon of Akkad proclaims that if most native-born citizens were farmers, a mass influx of immigrants would necessarily lower the average real income if those immigrants also became farmers. But that is not true — not if the immigrant farmers purchased the native-born farmers’ crops. Between 1820 and 1986, even as the ratio of farmworkers to workers in all other sectors dropped dramatically, the total number of people living and working on U.S. farms climbed from 2 million to 5 million. That was a net increase in the number of people competing in this sector, and yet the average U.S. farmworker had higher living standards in 1986 than in 1820 due to increased demand and also firms’ investments in efficiency-improving innovations."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)