"California’s gasoline market—throughout the entire supply chain—is

competitive but also features isolated choke points, bottlenecks, and

government interventions that result in a gasoline production and supply

network that is slower, more rigid, and less adaptive and efficient

than it otherwise could be. The overall effect is persistently higher

prices at the pump and greater price volatility during periods of

disruption. Those consequences stem from federal, state, and local

policies by the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,

the California State Legislature, the California Air Resources Board,

the California Environmental Protection Agency, California governors,

local boards of supervisors, and local city councils and mayors, among

others."

"Prices at different locations for crude oil will tend to move toward

parity as arbitrage occurs (the “law of one price”). Transaction costs

represent obstacles that keep prices from equalizing in the long run

along with local events that disrupt markets temporarily. It is fair to

say that the sources of crude oil used to refine California gasoline can

be, and have been, located almost anywhere in the world, including

California."

"California’s oil and gasoline industry is in some ways an isolated “fuel

island” cut off from adjustment mechanisms that are available in other

regions of the country. Market fundamentals and institutions explain

California gasoline prices without resorting to conspiracy theories

inconsistent with economic logic and the available data."

"The policy choices of officials drive retail gasoline prices higher by

30 percent to 70 percent or more in the Golden State, acting effectively

as a regressive tax hitting hardest the state’s poorest residents"

"different refinery designs and operating procedures are best suited to

process certain types of crude, most importantly “sweet” or “sour”

crude, defined by low or high sulfur concentration, respectively."

"Gasoline spending per capita in 2021 was highest in sparsely populated Wyoming ($1,756) and lowest in urbanized New York ($754).[3]

In 2009, California ranked 13th in per capita spending on gasoline, and

by 2021 it had fallen to 21st ($1,338). The average increase in

gasoline prices nationally from 2009 through 2021 was 30.7 percent, but

California’s increased by 57.9 percent. The price of crude oil delivered

to California also increased, but by a less extreme percentage."

"a recent report by investor website MarketWatch correctly claimed that

Californians paid nearly 70 percent more per gallon than the rest of the

country"

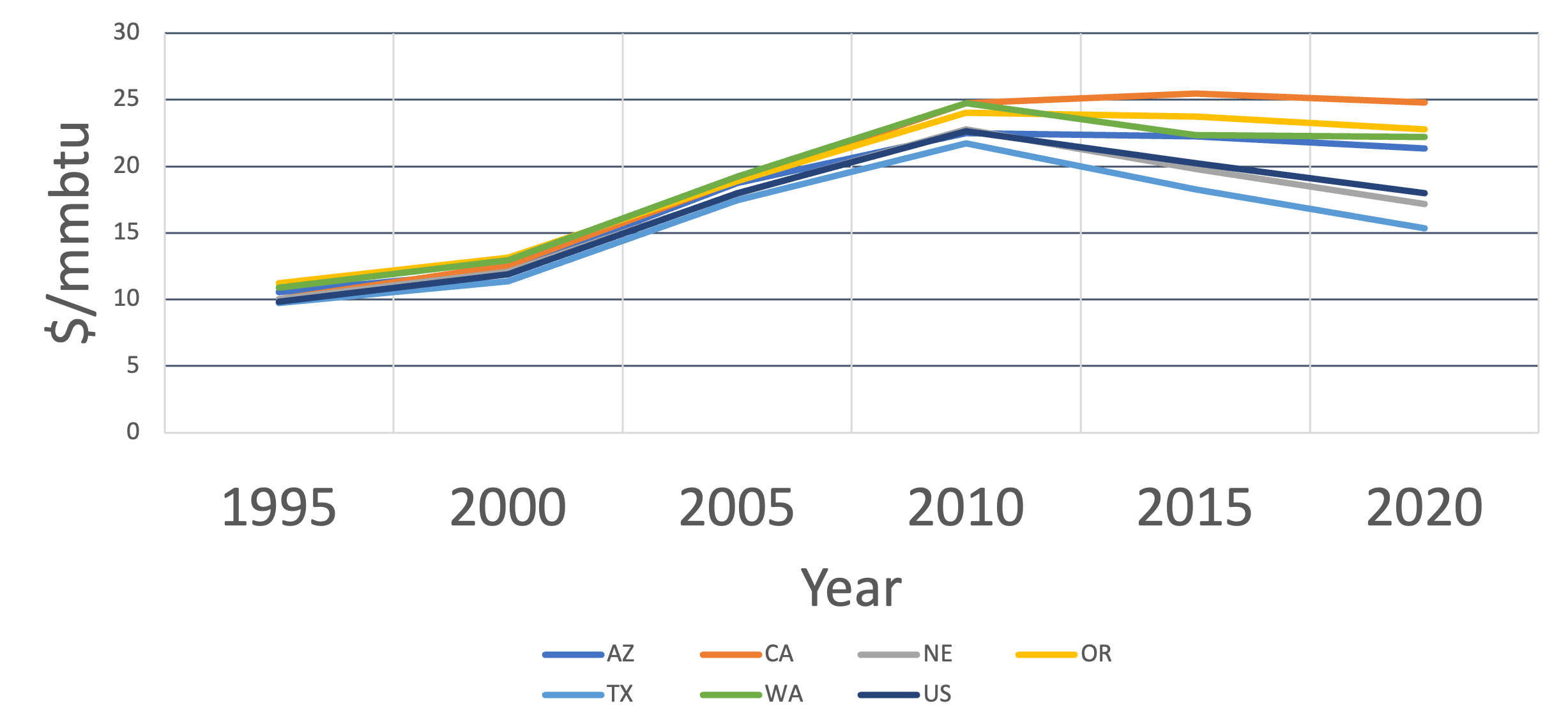

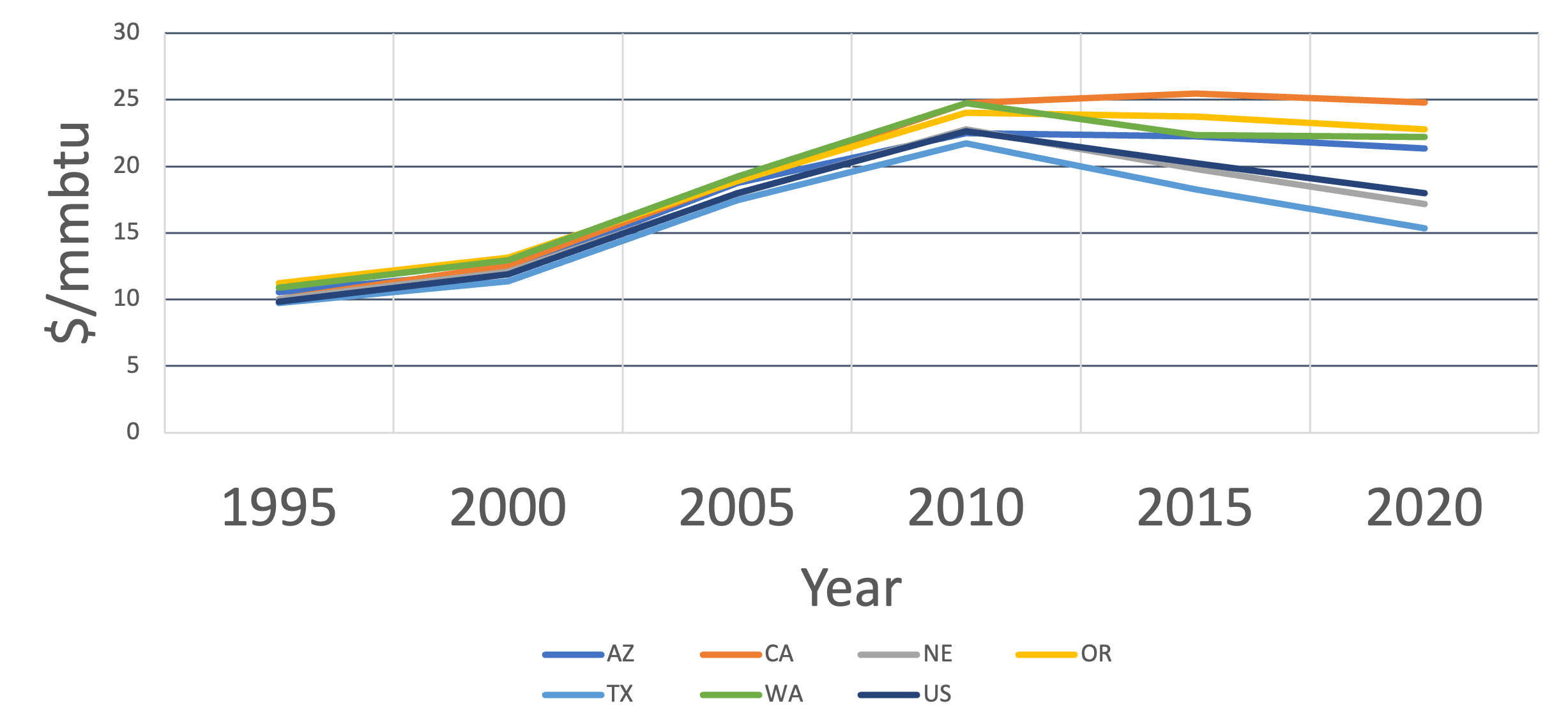

"only recently, around 2010, did California persistently become the highest-priced western state for gasoline."

Figure 1: The retail price of gasoline per MMBtu for selected U.S. states, 1995–2020.

Sources: U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information

Administration, State Energy Data System, State Profiles and Energy

Estimates, Motor Gasoline Price and Expenditure Estimates, Ranked by

State, 2021, table E20; U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information

Administration, Motor Gasoline Price and Expenditure Estimates

1970–2020, table F20; and U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information

Administration, Primary Energy, Electricity, and Total Energy Price and

Expenditure Estimates 1970–2021, table ET-1. "California became a high-price state for retail gasoline quite recently"

"To explain gasoline prices, we begin by examining the market process of

price convergence. Figure 2 shows prices for crude oil deliveries at

three important locations during a 10-year period."

Source: IndexMundi: Dated Brent, WTI, Dubai p

When transactions that exploit localized differences are reallocated,

prices become better indicators of relative scarcity and abundance over

wider areas. Changing prices facilitate adjustments to unexpected

events.

"The successful performance of crude oil markets that experience

surprise “shocks” is perhaps best illustrated by attempts to cartelize

oil markets by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Reaction to OPEC’s 1973 oil embargo was a textbook exercise in market

economics: The price for a barrel of oil quadrupled, and prices at the

pump roughly doubled. Non-member countries responded by producing larger

amounts of new oil, exploration activities burgeoned around the world,

and by the end of the decade OPEC’s influence on prices, if any, was

difficult to spot. OPEC infighting destroyed a united front going

forward. Over the longer term, producers innovated such new technologies

as directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking.

As time passed and technologies changed, new reactions to scarcity

became possible. Natural gas went from a local by-product of oil

extraction to an internationally traded commodity that moved globally on

ultra-cold liquefied natural gas tanker ships and increasingly competed

with oil.

The lesson: The data demonstrate that in

mature global markets such as crude oil, prices will tend to converge

over time and move together when events impact market participants.

Transaction costs represent “obstacles” that keep prices from equalizing

in the long run. Local events, such as refineries suddenly shutting

down due to unexpected maintenance, a fire, or a hurricane, can disrupt

markets temporarily—more so in California"

"Perhaps surprisingly to many people, California’s most important source

of crude oil in 2019 was California, 28.9 percent of the total processed

in the state. Alaska accounted for another 14.9 percent of the total.

Ongoing production declines and regulatory limits on exploration and

drilling have reduced domestic oil’s importance in California such that

by 2022 foreign sources dominated, especially Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, and

Iraq."

"Mexico’s history of oil field nationalization since the 1930s and its

problematic political relationship with the United States have combined

to reduce its actual and potential exports to the United States and

California. Canada sends substantial amounts of crude oil to the Midwest

and Northeast, but limited pipeline capacity leaves it with only a

small fraction of California’s market."

"California’s relatively small pipeline networks and storage capacities

limit the state’s use of regional throughput for gasoline and blending

components to less than 7 percent of total capacity. Since general

agreement apparently exists that politics and economics are combining to

shrink California’s oil consumption, there is little prospect on the

horizon that pipeline capacity will be expanded in California.

California refiners can send gasoline out of the state but have

virtually no import capability. The state refines most of Nevada’s, and

nearly half of Arizona’s, transport fuels.

Those constraints create scenarios wherein supply and demand can

become tight. Little spare capacity further limits California’s ability

to adjust to unforeseen events, and dependence on maritime shipping

makes adjustments even slower and more expensive. Sudden changes, such

as a refinery accident, can impose costs in California that would be

mitigated by slack capacity and pipeline arbitrage in less constrained

areas.

California’s ability to adjust is constrained by the law. In many

regions of the United States, a refinery accident leads to temporary

shortages and short-term price spikes. The shortfalls are relieved by

local action, such as more outside deliveries through pipelines. But in

California, where deliveries come by ship, the federal Jones Act

(enacted in 1920) requires that transportation between U.S. ports be

made on U.S.-flagged ships built in the United States and crewed largely

by American sailors. Spare tanker ship capacity is limited, and the

entry of additional shippers often is uneconomical.[13]

The Jones Act hampers seaborne tanker shipments to California,

increasing delays and reliance on trains and capacity-constrained

pipelines.

Long-term supply issues might be minor given the world market. But local

factors might cause significant short-run price spikes and supply

shortages, which are less likely in less constrained parts of the

country. California environmental regulations that require a special

fuel blend mean that its refiners and retailers cannot simply purchase

gasoline from other states, even if pipeline capacity was sufficiently

in place.

The supply-demand balance in California determines the choices of

producers and consumers, which are made under pervasive uncertainty. The

details of those choices are critical because they determine the

benefits that originate in markets and the distribution of those

benefits. Transactions may be short- or long-term, may be seasonally

variable, and can cover flows that are secure or not (“firm” or

“interruptible”). They apply to different possible mixes of crude inputs

and finished product outputs whose values depend on market prices, to

name only a few dimensions.

Many factors also impact the market structures of refining and

retailing, and their relationships. Gasoline sales involve a complex

volumetric interdependence between oil production, refining, and retail

gasoline distribution. Crude oil and refined products are costly and

dangerous to store, and the underlying chemistry of boiling and

evaporation limits the rates at which various products can be produced.

Most important, the high costs of interruptions require that the entire

process operate continuously. Minimizing long-term cost may entail

storing crude rather than refining it immediately, or not releasing from

storage a currently salable product because future operating costs

might be higher if it were sold today. Inventories and “buffer” supplies

are costly to maintain, but cost may be even higher if the operator

must make rapid adjustments.

Continuous operation requires a dependable incoming stream of crude

oil, in terms of both deliveries and the pricing of those deliveries.

The refiner’s limited and costly storage capacity requires that the

refiner have dependable outlets and prices for gasoline, which is most

efficiently produced in a continuous stream. Recognizing the realities

of the fuel production process helps to explain seeming anomalies that

many observers have viewed as evidence of monopoly.

Volumetric interdependence motivates large refiners, also known as

“majors,” to mitigate the risk of unsold output by vertically

integrating “backward” into exploration and production of crude oil that

they will use as scheduled. To solve their own inventory and continuity

problems, refiners also contract with “independent” specialist

producers like Apache and Devon for additional crude oil supplies or to

reduce the costs of maintaining inventories.

One common solution balances the costs and benefits for oil producers

and gasoline retailers by binding them into long-term relationships with

franchise contracts that can be terminated only by mutual agreement.

The refiner sets its price in the face of market conditions (including

competition from other refiners) but cannot specify the price that a

retailer legally can charge. Under a voluntarily entered contract with

the refiner, the retailer is said to be “captive,” and, absent special

arrangements, it can deal only with that refiner. The franchise

contract, however, typically rewards efforts by gas stations to sell

goods such as tires and minor repairs as allowed by the station’s parent

brand, which itself has a reputation to protect by maintaining customer

loyalty."

As "Vehicles became more technologically complex and heavily regulated for

pollution and safety in ways that benefited auto dealerships over corner

gasoline stations, leaving retail stations with low-margin residual

business (fixing flat tires, for example) and reducing their incentives

to make gasoline-related sales efforts to win motorist loyalty."

"customers had become less loyal to established brands and increasingly

sought low prices while retail margins on gasoline fell. The “service

station” that once sold both gasoline and repairs is giving way to

enterprises (“pumpers”) working to maximize income from low-price

gasoline sales and downplaying services. Yet another consequence has

been the rise of the “convenience store,” which is typically not

operated by the fuel supplier and offers low-price gasoline to draw

people into the store, where higher-margin merchandise is sold."

"California is in many ways a “fuel island,” cut off from adjustment

mechanisms that are available in other regions of the country. Supply

shocks cause greater and longer-lasting price spikes in California

because of the state’s unfortunate reliance on capacity-constrained

pipelines and ships to move crude oil and gasoline. California’s strict

environmental fuel standards make it impossible for

gasoline refined elsewhere to be simply transported to California when

prices rise. Contractual arrangements, such as franchise agreements and

vertically integrated production and distribution structures, are not

evidence of monopolistic behavior. Rather, they provide efficiency

benefits to producers and consumers, especially as technology and

regulations have changed."

Source: California Energy Commission, “Estimated Gasoline Price

Breakdown and Margins,” July 17, 2023.

The average retail price per gallon of branded gasoline in

California on July 17, 2023, was $4.721, about $1.20 (or 34 percent)

more than the national average of $3.53 on the same date.[15]

In recent months, California’s average gasoline prices have been about

$1.20 to $1.50 above the national average per gallon. The difference was

much larger during the summer and fall of 2022, during the peak of then

record-breaking prices."

"During normal times, the average retail price for a gallon of

gasoline in California is 30 percent to 40 percent higher than the

national average. But the difference can spike temporarily to 70 percent

or more during periods of significant disruption in the supply chain

(for example, on September 27, 2023, the price difference was 54 percent

or $2.06 per gallon due to several supply shocks).

Comparing California’s percentage breakdown in Figure 6 with the national average breakdown[20]

shows that California’s price differential of $1.20 is driven by three

components: about 32 cents more per gallon explained by a higher state

excise tax (26 percent of the difference), 42 cents more per gallon

attributable to higher refinery costs (35 percent of the difference),

and 51 cents more per gallon resulting from greater environmental

regulatory costs plus other state and local taxes and fees, such as

sales taxes (42 percent of the difference). As economic theory predicts,

the crude oil price differential was just 2 cents per gallon,

supporting the law of one price. In other words, higher taxes, stricter

environmental regulations, and unique fuel island effects explain the

higher gasoline prices in California compared with prices experienced

elsewhere. The share attributable to fuel island effects surges

typically during periods of sizable disruption, such as a significant

break in the supply chain."

"Greed, however, cannot be the explanation because both buyers and

sellers invariably are self-interested. No plausible reasons can be

found for believing that producers, refiners, and retailers somehow

became greedier overnight in the summer of 2022, and then became less

greedy overnight, allowing prices to fall later in the year. Instead,

the fundamentals of supply and demand changed during that summer and

fall within California’s unique institutional regime, which explains the

behavior of gasoline prices.

Selective data frequently are cited to substantiate allegations of greed

and “windfall profits” by producers. Gasoline, however, can be

relatively abundant or relatively scarce. The relevant question is

whether oil and gasoline sellers persistently are more profitable than

those in comparably risky businesses. It is not enough to present data

on high prices or profits without showing that they resulted from

activities beyond ordinary competition. If price fixing exists, it is

subject to state and federal antitrust laws, and hefty profits await

those who spot it and succeed in court. As we have seen, global markets

tend to converge around a single price, and the recent U.S. experience

is part of it. Prices around the world were comparably high in the

summer and fall of 2022, and they moved in parallel, but the record

fails to show evidence of monopoly."

"On September 30, 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom directed the California Air

Resources Board to make an early transition to mandatory use of

lower-cost winter blend gasoline.[23]

On the same day, Newsom noted that crude oil had fallen from roughly

$100 per barrel at the end of August to about $85 per barrel during the

following 30 days, while gasoline prices had risen from $5.06 per gallon

to $6.29. He said, “We’re not going to stand by while greedy oil

companies fleece Californians. Instead, I’m calling for a windfall tax

to ensure excess oil profits go back to help millions of Californians

who are getting ripped off.”

Few if any reasons exist for believing that a windfall profits tax would

do anything more than effect minor transfers of wealth among

Californians. In 1980, the U.S. Congress and President Jimmy Carter

enacted the Crude Oil Windfall Profit Tax Act. According to Ajay K.

Mehrotra, a professor of law and history at Northwestern University, for

a variety of reasons, “[m]ost economists declared it a colossal

failure.” He went on to conclude that such excess and windfall profits

taxes “rarely deliver on their promise of greater enduring tax equity.”"

"The CEC [California Energy Commission ] and other state agencies have failed to unearth data that

would support a valid conclusion of monopoly or price fixing. Responding

to an earlier inquiry in 2019 on the causes of price increases, a CEC

report noted,

[it] does not have any evidence that gasoline retailers fixed prices or engaged in false advertising."

"As an example of the factors that must be accounted for to substantiate a

charge of profiteering, consider the summer of 2022. Retail gasoline

prices were high, but sales volumes were lower than expected.

Nevertheless, station profitability during the summer driving season was

roughly 70 to 90 percent higher than in the past three summer driving

seasons. It was among the most profitable periods on record, as the

growth in margins outweighed the decline in volumes.

"Consistent use of competitive bidding among private companies, without

union-labor and prevailing-wage mandates, to fix and build roads and

bridges could lower overall costs, allowing excise taxes or

mileage-based user fees to be reduced over time. It costs California

$44,831 to maintain each lane-mile of state roadway—the fourth-highest

rate in the nation, which may explain why California’s gasoline excise

taxes are so high, compared with those of other states."

"California leads the nation in the prohibition of new gas stations and new fuel pumps at existing gas stations"

"A consequence of fewer gas stations is that many consumers must drive

farther to fuel their vehicles, which not only consumes more gasoline,

but it can also force consumers to use gas stations in more dangerous

areas."

"Oil drilling in California has also been curtailed, and new prohibitions

have been enacted recently, ostensibly to combat climate change and

advance “environmental justice.” As early as 1969, California stopped

issuing new permits for offshore oil drilling in state waters.[40]

In 2021, Los Angeles County supervisors voted unanimously to prohibit

new drilling and phase out existing oil and natural gas wells in

unincorporated areas of the county."

"California’s summer seasonal fuel blend, intended to reduce unhealthy

ozone and smog levels, especially in the Los Angeles area, is more

expensive for refiners to produce than the winter fuel blend.[37]

The seasonal fuel blends plus California’s “reformulated gasoline”

requirement (which is designed to burn cleaner) create a “fuel island”

effect in California, since refiners and retailers cannot simply buy

gasoline from other states in a pinch to meet demand."