Blame Politicians, Not Producers, for High California Gasoline Prices

By Robert J. Michaels & Lawrence J. McQuillan. Robert J. Michaels is Professor Emeritus of Economics at California State University, Fullerton. Lawrence J. McQuillan is Senior Fellow at the Independent Institute.

"California’s gasoline market—throughout the entire supply chain—is competitive but also features isolated choke points, bottlenecks, and government interventions that result in a gasoline production and supply network that is slower, more rigid, and less adaptive and efficient than it otherwise could be. The overall effect is persistently higher prices at the pump and greater price volatility during periods of disruption. Those consequences stem from federal, state, and local policies by the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the California State Legislature, the California Air Resources Board, the California Environmental Protection Agency, California governors, local boards of supervisors, and local city councils and mayors, among others."

"Prices at different locations for crude oil will tend to move toward parity as arbitrage occurs (the “law of one price”). Transaction costs represent obstacles that keep prices from equalizing in the long run along with local events that disrupt markets temporarily. It is fair to say that the sources of crude oil used to refine California gasoline can be, and have been, located almost anywhere in the world, including California."

"California’s oil and gasoline industry is in some ways an isolated “fuel island” cut off from adjustment mechanisms that are available in other regions of the country. Market fundamentals and institutions explain California gasoline prices without resorting to conspiracy theories inconsistent with economic logic and the available data."

"The policy choices of officials drive retail gasoline prices higher by 30 percent to 70 percent or more in the Golden State, acting effectively as a regressive tax hitting hardest the state’s poorest residents"

"different refinery designs and operating procedures are best suited to process certain types of crude, most importantly “sweet” or “sour” crude, defined by low or high sulfur concentration, respectively."

"Gasoline spending per capita in 2021 was highest in sparsely populated Wyoming ($1,756) and lowest in urbanized New York ($754).[3] In 2009, California ranked 13th in per capita spending on gasoline, and by 2021 it had fallen to 21st ($1,338). The average increase in gasoline prices nationally from 2009 through 2021 was 30.7 percent, but California’s increased by 57.9 percent. The price of crude oil delivered to California also increased, but by a less extreme percentage."

"a recent report by investor website MarketWatch correctly claimed that Californians paid nearly 70 percent more per gallon than the rest of the country"

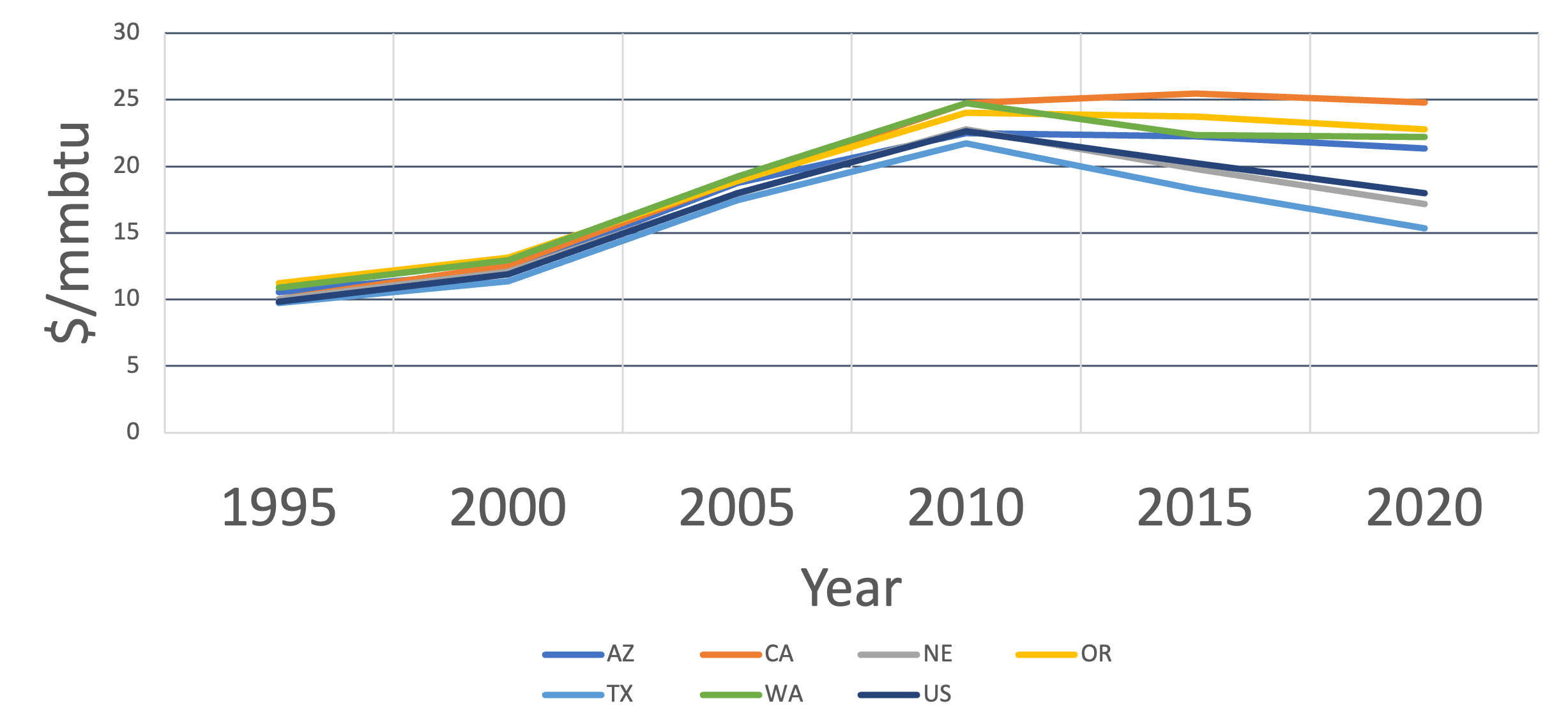

"only recently, around 2010, did California persistently become the highest-priced western state for gasoline."

Figure 1: The retail price of gasoline per MMBtu for selected U.S. states, 1995–2020.Sources: U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, State Energy Data System, State Profiles and Energy Estimates, Motor Gasoline Price and Expenditure Estimates, Ranked by State, 2021, table E20; U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Motor Gasoline Price and Expenditure Estimates 1970–2020, table F20; and U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Primary Energy, Electricity, and Total Energy Price and Expenditure Estimates 1970–2021, table ET-1."California became a high-price state for retail gasoline quite recently"

"To explain gasoline prices, we begin by examining the market process of price convergence. Figure 2 shows prices for crude oil deliveries at three important locations during a 10-year period."

Source: IndexMundi: Dated Brent, WTI, Dubai p

When transactions that exploit localized differences are reallocated, prices become better indicators of relative scarcity and abundance over wider areas. Changing prices facilitate adjustments to unexpected events.

"The successful performance of crude oil markets that experience surprise “shocks” is perhaps best illustrated by attempts to cartelize oil markets by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Reaction to OPEC’s 1973 oil embargo was a textbook exercise in market economics: The price for a barrel of oil quadrupled, and prices at the pump roughly doubled. Non-member countries responded by producing larger amounts of new oil, exploration activities burgeoned around the world, and by the end of the decade OPEC’s influence on prices, if any, was difficult to spot. OPEC infighting destroyed a united front going forward. Over the longer term, producers innovated such new technologies as directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking. As time passed and technologies changed, new reactions to scarcity became possible. Natural gas went from a local by-product of oil extraction to an internationally traded commodity that moved globally on ultra-cold liquefied natural gas tanker ships and increasingly competed with oil.

The lesson: The data demonstrate that in mature global markets such as crude oil, prices will tend to converge over time and move together when events impact market participants. Transaction costs represent “obstacles” that keep prices from equalizing in the long run. Local events, such as refineries suddenly shutting down due to unexpected maintenance, a fire, or a hurricane, can disrupt markets temporarily—more so in California"

"Perhaps surprisingly to many people, California’s most important source of crude oil in 2019 was California, 28.9 percent of the total processed in the state. Alaska accounted for another 14.9 percent of the total. Ongoing production declines and regulatory limits on exploration and drilling have reduced domestic oil’s importance in California such that by 2022 foreign sources dominated, especially Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, and Iraq."

"Mexico’s history of oil field nationalization since the 1930s and its problematic political relationship with the United States have combined to reduce its actual and potential exports to the United States and California. Canada sends substantial amounts of crude oil to the Midwest and Northeast, but limited pipeline capacity leaves it with only a small fraction of California’s market."

"California’s relatively small pipeline networks and storage capacities limit the state’s use of regional throughput for gasoline and blending components to less than 7 percent of total capacity. Since general agreement apparently exists that politics and economics are combining to shrink California’s oil consumption, there is little prospect on the horizon that pipeline capacity will be expanded in California. California refiners can send gasoline out of the state but have virtually no import capability. The state refines most of Nevada’s, and nearly half of Arizona’s, transport fuels.

Those constraints create scenarios wherein supply and demand can become tight. Little spare capacity further limits California’s ability to adjust to unforeseen events, and dependence on maritime shipping makes adjustments even slower and more expensive. Sudden changes, such as a refinery accident, can impose costs in California that would be mitigated by slack capacity and pipeline arbitrage in less constrained areas.

California’s ability to adjust is constrained by the law. In many regions of the United States, a refinery accident leads to temporary shortages and short-term price spikes. The shortfalls are relieved by local action, such as more outside deliveries through pipelines. But in California, where deliveries come by ship, the federal Jones Act (enacted in 1920) requires that transportation between U.S. ports be made on U.S.-flagged ships built in the United States and crewed largely by American sailors. Spare tanker ship capacity is limited, and the entry of additional shippers often is uneconomical.[13] The Jones Act hampers seaborne tanker shipments to California, increasing delays and reliance on trains and capacity-constrained pipelines.

Long-term supply issues might be minor given the world market. But local factors might cause significant short-run price spikes and supply shortages, which are less likely in less constrained parts of the country. California environmental regulations that require a special fuel blend mean that its refiners and retailers cannot simply purchase gasoline from other states, even if pipeline capacity was sufficiently in place.

The supply-demand balance in California determines the choices of producers and consumers, which are made under pervasive uncertainty. The details of those choices are critical because they determine the benefits that originate in markets and the distribution of those benefits. Transactions may be short- or long-term, may be seasonally variable, and can cover flows that are secure or not (“firm” or “interruptible”). They apply to different possible mixes of crude inputs and finished product outputs whose values depend on market prices, to name only a few dimensions.

Many factors also impact the market structures of refining and retailing, and their relationships. Gasoline sales involve a complex volumetric interdependence between oil production, refining, and retail gasoline distribution. Crude oil and refined products are costly and dangerous to store, and the underlying chemistry of boiling and evaporation limits the rates at which various products can be produced. Most important, the high costs of interruptions require that the entire process operate continuously. Minimizing long-term cost may entail storing crude rather than refining it immediately, or not releasing from storage a currently salable product because future operating costs might be higher if it were sold today. Inventories and “buffer” supplies are costly to maintain, but cost may be even higher if the operator must make rapid adjustments.

Continuous operation requires a dependable incoming stream of crude oil, in terms of both deliveries and the pricing of those deliveries. The refiner’s limited and costly storage capacity requires that the refiner have dependable outlets and prices for gasoline, which is most efficiently produced in a continuous stream. Recognizing the realities of the fuel production process helps to explain seeming anomalies that many observers have viewed as evidence of monopoly.

Volumetric interdependence motivates large refiners, also known as “majors,” to mitigate the risk of unsold output by vertically integrating “backward” into exploration and production of crude oil that they will use as scheduled. To solve their own inventory and continuity problems, refiners also contract with “independent” specialist producers like Apache and Devon for additional crude oil supplies or to reduce the costs of maintaining inventories.

One common solution balances the costs and benefits for oil producers and gasoline retailers by binding them into long-term relationships with franchise contracts that can be terminated only by mutual agreement. The refiner sets its price in the face of market conditions (including competition from other refiners) but cannot specify the price that a retailer legally can charge. Under a voluntarily entered contract with the refiner, the retailer is said to be “captive,” and, absent special arrangements, it can deal only with that refiner. The franchise contract, however, typically rewards efforts by gas stations to sell goods such as tires and minor repairs as allowed by the station’s parent brand, which itself has a reputation to protect by maintaining customer loyalty."

As "Vehicles became more technologically complex and heavily regulated for pollution and safety in ways that benefited auto dealerships over corner gasoline stations, leaving retail stations with low-margin residual business (fixing flat tires, for example) and reducing their incentives to make gasoline-related sales efforts to win motorist loyalty."

"customers had become less loyal to established brands and increasingly sought low prices while retail margins on gasoline fell. The “service station” that once sold both gasoline and repairs is giving way to enterprises (“pumpers”) working to maximize income from low-price gasoline sales and downplaying services. Yet another consequence has been the rise of the “convenience store,” which is typically not operated by the fuel supplier and offers low-price gasoline to draw people into the store, where higher-margin merchandise is sold."

"California is in many ways a “fuel island,” cut off from adjustment mechanisms that are available in other regions of the country. Supply shocks cause greater and longer-lasting price spikes in California because of the state’s unfortunate reliance on capacity-constrained pipelines and ships to move crude oil and gasoline. California’s strict environmental fuel standards make it impossible for gasoline refined elsewhere to be simply transported to California when prices rise. Contractual arrangements, such as franchise agreements and vertically integrated production and distribution structures, are not evidence of monopolistic behavior. Rather, they provide efficiency benefits to producers and consumers, especially as technology and regulations have changed."

Source: California Energy Commission, “Estimated Gasoline Price Breakdown and Margins,” July 17, 2023.

The average retail price per gallon of branded gasoline in California on July 17, 2023, was $4.721, about $1.20 (or 34 percent) more than the national average of $3.53 on the same date.[15] In recent months, California’s average gasoline prices have been about $1.20 to $1.50 above the national average per gallon. The difference was much larger during the summer and fall of 2022, during the peak of then record-breaking prices."

"During normal times, the average retail price for a gallon of gasoline in California is 30 percent to 40 percent higher than the national average. But the difference can spike temporarily to 70 percent or more during periods of significant disruption in the supply chain (for example, on September 27, 2023, the price difference was 54 percent or $2.06 per gallon due to several supply shocks).

Comparing California’s percentage breakdown in Figure 6 with the national average breakdown[20] shows that California’s price differential of $1.20 is driven by three components: about 32 cents more per gallon explained by a higher state excise tax (26 percent of the difference), 42 cents more per gallon attributable to higher refinery costs (35 percent of the difference), and 51 cents more per gallon resulting from greater environmental regulatory costs plus other state and local taxes and fees, such as sales taxes (42 percent of the difference). As economic theory predicts, the crude oil price differential was just 2 cents per gallon, supporting the law of one price. In other words, higher taxes, stricter environmental regulations, and unique fuel island effects explain the higher gasoline prices in California compared with prices experienced elsewhere. The share attributable to fuel island effects surges typically during periods of sizable disruption, such as a significant break in the supply chain."

"Greed, however, cannot be the explanation because both buyers and sellers invariably are self-interested. No plausible reasons can be found for believing that producers, refiners, and retailers somehow became greedier overnight in the summer of 2022, and then became less greedy overnight, allowing prices to fall later in the year. Instead, the fundamentals of supply and demand changed during that summer and fall within California’s unique institutional regime, which explains the behavior of gasoline prices.

Selective data frequently are cited to substantiate allegations of greed and “windfall profits” by producers. Gasoline, however, can be relatively abundant or relatively scarce. The relevant question is whether oil and gasoline sellers persistently are more profitable than those in comparably risky businesses. It is not enough to present data on high prices or profits without showing that they resulted from activities beyond ordinary competition. If price fixing exists, it is subject to state and federal antitrust laws, and hefty profits await those who spot it and succeed in court. As we have seen, global markets tend to converge around a single price, and the recent U.S. experience is part of it. Prices around the world were comparably high in the summer and fall of 2022, and they moved in parallel, but the record fails to show evidence of monopoly."

"On September 30, 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom directed the California Air Resources Board to make an early transition to mandatory use of lower-cost winter blend gasoline.[23] On the same day, Newsom noted that crude oil had fallen from roughly $100 per barrel at the end of August to about $85 per barrel during the following 30 days, while gasoline prices had risen from $5.06 per gallon to $6.29. He said, “We’re not going to stand by while greedy oil companies fleece Californians. Instead, I’m calling for a windfall tax to ensure excess oil profits go back to help millions of Californians who are getting ripped off.”

Few if any reasons exist for believing that a windfall profits tax would do anything more than effect minor transfers of wealth among Californians. In 1980, the U.S. Congress and President Jimmy Carter enacted the Crude Oil Windfall Profit Tax Act. According to Ajay K. Mehrotra, a professor of law and history at Northwestern University, for a variety of reasons, “[m]ost economists declared it a colossal failure.” He went on to conclude that such excess and windfall profits taxes “rarely deliver on their promise of greater enduring tax equity.”"

"The CEC [California Energy Commission ] and other state agencies have failed to unearth data that would support a valid conclusion of monopoly or price fixing. Responding to an earlier inquiry in 2019 on the causes of price increases, a CEC report noted,

[it] does not have any evidence that gasoline retailers fixed prices or engaged in false advertising."

"As an example of the factors that must be accounted for to substantiate a charge of profiteering, consider the summer of 2022. Retail gasoline prices were high, but sales volumes were lower than expected. Nevertheless, station profitability during the summer driving season was roughly 70 to 90 percent higher than in the past three summer driving seasons. It was among the most profitable periods on record, as the growth in margins outweighed the decline in volumes.

"Consistent use of competitive bidding among private companies, without union-labor and prevailing-wage mandates, to fix and build roads and bridges could lower overall costs, allowing excise taxes or mileage-based user fees to be reduced over time. It costs California $44,831 to maintain each lane-mile of state roadway—the fourth-highest rate in the nation, which may explain why California’s gasoline excise taxes are so high, compared with those of other states."

"California leads the nation in the prohibition of new gas stations and new fuel pumps at existing gas stations"

"A consequence of fewer gas stations is that many consumers must drive farther to fuel their vehicles, which not only consumes more gasoline, but it can also force consumers to use gas stations in more dangerous areas."

"Oil drilling in California has also been curtailed, and new prohibitions have been enacted recently, ostensibly to combat climate change and advance “environmental justice.” As early as 1969, California stopped issuing new permits for offshore oil drilling in state waters.[40] In 2021, Los Angeles County supervisors voted unanimously to prohibit new drilling and phase out existing oil and natural gas wells in unincorporated areas of the county."

"California’s summer seasonal fuel blend, intended to reduce unhealthy ozone and smog levels, especially in the Los Angeles area, is more expensive for refiners to produce than the winter fuel blend.[37] The seasonal fuel blends plus California’s “reformulated gasoline” requirement (which is designed to burn cleaner) create a “fuel island” effect in California, since refiners and retailers cannot simply buy gasoline from other states in a pinch to meet demand."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.