By Stuart Hayashi of Arc Digital. Excerpt:

"These pundits overlook two important considerations.

First, when foreign-born laborers get off from work for the day, do they not take the money they earned and exchange it for products they need? Foreign-born workers need food and other amenities, which they procure from businesses. As they serve a growing number of foreign-born customers, these businesses notice they are understaffed. The businesses’ drive to meet the foreign-born workers’ demand for their wares, in turn, raises these businesses’ demand for employees, bidding wages upward. Texas Tech University’s Benjamin Powell (1, 2) and the Cato Institute’s Alex Nowrasteh corroborate this interpretation.

A case study: despite Trump’s recent fretting over a caravan of 7,000 Honduran asylum-seekers, that is less than one-tenth as many people as the 125,000 Cuban refugees who arrived in Miami on rickety boats between April and October 1980. This mass migration expanded the city workforce’s overall size by 7 percent, with the size of the unskilled workforce growing by one-fifth. When economist David Card looked into the long-term consequences, he found no decrease in Miami’s employment levels or wages.

If real wages descended for the long term, workers would see no real gains. But they do. Mexicans came to the U.S. between 1941 and 1964 for agricultural jobs, and their children and grandchildren moved into more-skilled employment, some coming to own their own vineyards. This is comparable to how workers who toiled in Mattel’s toy factories in Taiwan in the 1970s ascended to First-World affluence within three decades.

Second, immigration skeptics characterize U.S. firms’ preference for hiring foreign-born workers as some initiative to cut costs. Yet most of the cost-cutting that has displaced traditional forms of native-born employment comes not from the hiring of foreign-born workers but from innovations in automation that produce more units of output with ever-smaller and ever-fewer inputs of labor and natural resources. Whatever the main factor in cutting costs, it is not as if domestic firms make no use of the money they save. They re-invest the cost savings into new operations, which benefits native-born workers through two paths: new operations are staffed by new hires, and, when the savings are invested in efficiency-improving technologies, native-born workers put in fewer hours of work than their parents did to produce and purchase the very same goods. Thus, as the U.S. industrialized between 1860 and 1890, its foreign-born population rose from 4.1 to 9.2 million, while its manufacturing workers experienced a 50 percent gain in real wages.

As Örn Bodvarsson and colleagues observe, this is a principle explained by a classical economist whom Thomas Jefferson praised as greater than Adam Smith: Jean-Baptiste Say. It is Say’s Law of Markets.

To have demand for a commodity is not merely to desire it, but to be both willing and able to exchange something for it. You only have demand for anything once you possess a supply of something that is of value to others — such as your capacity to perform jobs for others. Say articulates:

We do not in reality buy the objects we consume with money or circulating coin which we pay for them. We must in the first place have bought this money itself by the sale of productions of our own.

Your devotion of time at work is what you trade in exchange for products that other workers were hired to craft.

Because money is but a tool for facilitating the trade of one set of goods for another, all money gets traded away in the long run. This is one reason why firms re-invest the money saved from their cost-cutting. Hence, Say phrases his Law thusly:

As soon as [foreign-born workers] are provided with the means of producing [jobs being such means], they appropriate their productions to their wants; ...we [workers] offer (or supply) productive means, and demand in return the thing of which we feel the greatest want (emphases Say’s).

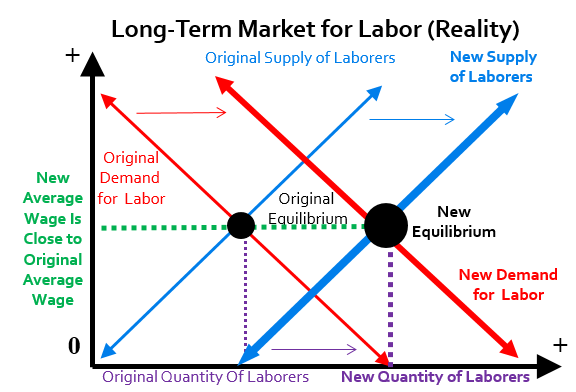

As every dollar earned will inevitably be spent, demand is ultimately the mirror image of supply. And the quantity by which foreign-born people increase the supply of productive labor is also an increase in demand for still more productive work, including the work of native-born citizens.

Regrettably, even the center-left’s ostensive “defenses” of immigration against conservatives decidedly snub Say’s Law. Writing in The Washington Post “Wonkblog,” Mike Konczal denies that immigrants adversely affect native-born citizens, but mostly because, Konczal maintains, the jobs for which unskilled immigrants compete are not the same jobs that native-born citizens covet.

Through similar reasoning, Sargon of Akkad proclaims that if most native-born citizens were farmers, a mass influx of immigrants would necessarily lower the average real income if those immigrants also became farmers. But that is not true — not if the immigrant farmers purchased the native-born farmers’ crops. Between 1820 and 1986, even as the ratio of farmworkers to workers in all other sectors dropped dramatically, the total number of people living and working on U.S. farms climbed from 2 million to 5 million. That was a net increase in the number of people competing in this sector, and yet the average U.S. farmworker had higher living standards in 1986 than in 1820 due to increased demand and also firms’ investments in efficiency-improving innovations."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.