By Peter C. Earle & Thomas Savidge. They are both Research Fellows at the American Institute for Economic Research. Excerpts:

"While the BEA publishes

a measurement titled “Value Added by Private Industries (VAPI),” it

does not get nearly as much attention as it deserves. The most recent

data show that VAPI contributes

to just under 89 percent of all economic growth. Despite this, GDP is

still the more prominent metric, in part because the BEA treats

government spending as a value added to the economy."

"VAPI includes private outputs that are purchased by government (i.e. a

defense contractor) while GDPP (Gross Domestic Private Product) treats those purchases as part of

“Government Consumption and Gross Investment.”"

"A cursory glance at the BEA’s description of government assumes

that all levels of government “contribute to the nation’s economy when

they provide services to the public and when they invest in capital.

They also provide social benefits, such as Social Security and Medicare,

to households.”

The description also notes that the government gets its revenue

taxes, transfers, and fines, as well as rent and royalties. It fails to

mention, however, that government receipts come at a cost. That cost,

what economists call opportunity cost, is the next-highest valued use of that money.

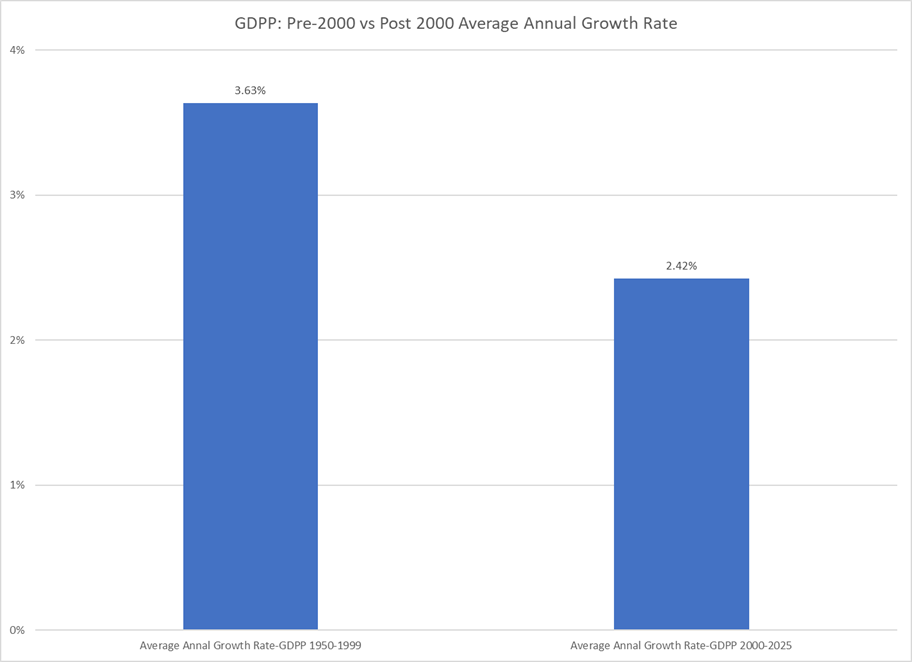

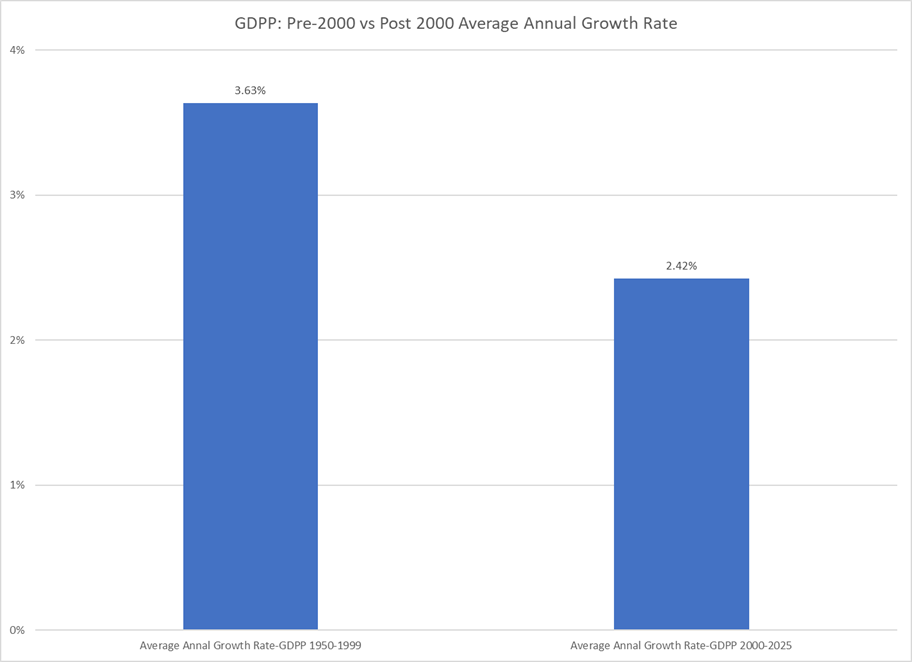

We can see this effect reflected in the BEA’s own data. When

examining the growth of government and the private sector both before

and after 2000 in our analysis published

last year, government growth (both federal as well as state and local)

outpaced that of the private sector. Below is an updated analysis of

last year’s findings. Note that the same still holds true: Government

outpaces the growth of the private sector, especially state and local

governments.

Source: United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of

Commerce. Table 1.1.6 Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars,

Authors’ Calculations.

Source: United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of

Commerce. Table 1.1.6 Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars,

Authors’ Calculations.

Furthermore, we find that the private sector has grown 33 percent slower

per year since the start of the new millennium. It is also important to

remember that transfer payments, such as Social Security or

unemployment insurance, are excluded from GDP estimates of government

spending because those transfers are counted toward private spending.

Furthermore, we find that the private sector has grown 33 percent slower

per year since the start of the new millennium. It is also important to

remember that transfer payments, such as Social Security or

unemployment insurance, are excluded from GDP estimates of government

spending because those transfers are counted toward private spending.

Source: United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of

Commerce. Table 1.1.6 Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars,

Authors’ Calculations.

A recent review

of the academic literature on government stimulus in the economy finds

that government stimulus makes, at best, modest, short-term

contributions to economic activity. In the long-term, however, the

review finds that government stimulus effects “often diminish or turn

negative due to reduced private investment and consumption, emphasizing

the role of anticipatory effects and private-sector responses.”

Economists, both past and present, have argued that calculating

government contributions to the economy is more complicated than

official GDP calculations claim. Economist Patrick Newman notes Nobel Prize-Winning Economist Simon Kuznets’s own objections

that government was treated as “an ultimate consumer” on par with

private consumers regardless of whether private citizens valued

government consumption and investment. Newman takes Kuznets’s concerns

further and argues that such positive treatment of government in

economic growth calculations opened the door to the flawed views of

Modern Monetary Theory.

Alternatively, economists Vincent Geloso and Chandler S. Reilly examine

government consumption and investment minus defense spending, called

“Defense-Adjusted National Accounts”. The result is a much lower level

of GDP, but the clear lesson “that wars do not improve living standards.” These challenges to the status quo

of economic growth calculations help, in the words of Geloso and

Reilly, “bridge the gap between official economic data and the

perceptions of the American public.”"