"I get this a lot: Why do you care so much about trying to accelerate productivity and economic growth? Are you some sort of neoliberal, “Make the line go up,” “What’s good for Wall Street is good for America” obsessive sicko? If you were a regular New York Times reader, you would know all about the “productivity and pay gap,” the long-term delinkage between worker output per hour and worker compensation. Productivity and economic growth don’t matter, redistribution does. I thought you worked at a think tank. Maybe you need to think harder, dude!

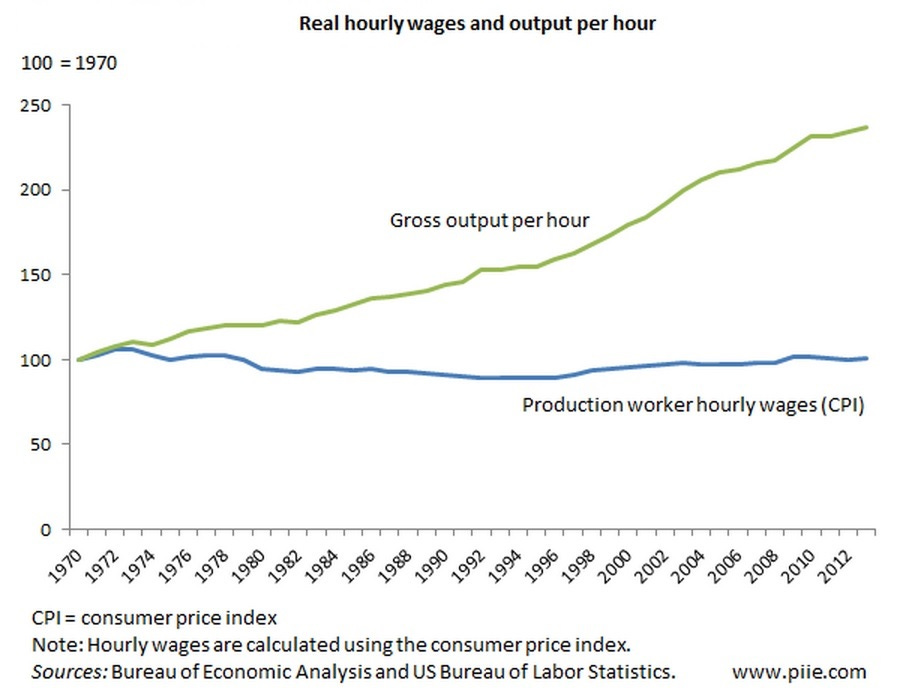

Well, something like that, I guess. Anyway, the popular notion that productivity no longer drives compensation — productivity growth may have been slow since the 1970s, but inflation-adjusted pay has been stagnant — is reflected in various versions of this chart:

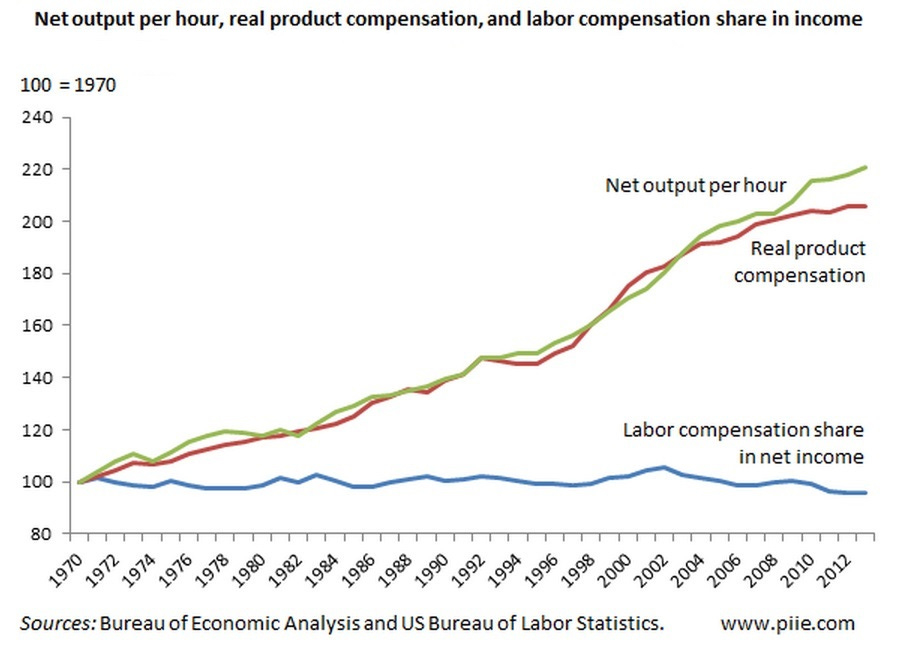

Mind the (productivity-pay) gap! But that chart sends a misleading message. And voracious news consumers who’ve seen it, or something like it, may have been confused by my recent 5QQ interview with AEI economist Michael Strain. He advocated “lighter taxes on business investment” because that would “lead to higher worker productivity,’ which in turn ‘would lead to higher wages for workers.” It’s the sort of policy recommendation that emerges from an understanding of this chart:

Robert Lawrence of the Peterson Institute created both of the above charts a few years back, and he contends the second chart better reflects the tight productivity-compensation relationship. Why the difference between the two charts? Lawrence made several modifications to the first one: (a) adjusted for an overly narrow definition of workers; (b) added in benefits to wages, (c) used an inflation measure that better accounts for what workers actually purchase; and (d) used a more relevant productivity measure.

Stagnant pay?

Key to the productivity-pay gap claim is the notion that since the early 1970s, real wages have gone pretty much nowhere. Maybe just a tiny 5 percent gain since the Nixon administration. Sure looks like stagnation, or a pretty close facsimile.

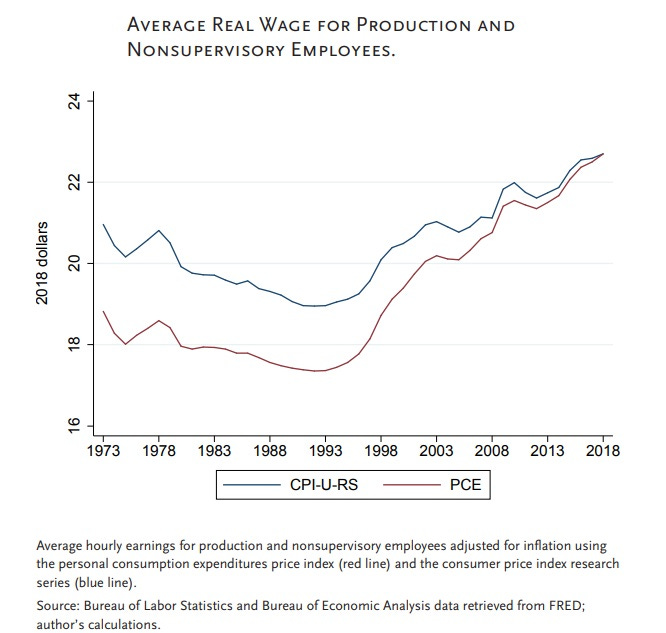

But using that 5 percent number to encapsulate some five decades of American economic history is problematic. Since the 1990 business cycle peak, wages are up 20 percent in real terms. And if you use the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index rather than the Consumer Price Index as the inflation measure — it’s the one preferred by the Federal Reserve and Congressional Budget Office — you find a 32 percent increase in average worker wages and about the same for the bottom fifth of workers. Fun fact: Broader after-tax income measures show middle-class living standards up by 42 percent since 1979 and 70 percent for the bottom fifth. (For more on all of this, I highly recommend Strain’s 2019 book The American Dream Is Not Dead, from which the below chart is taken.)

Productivity growth never stopped mattering for wage growth

In “Productivity and Pay: Is the link broken?” Harvard University’s Anna Stansbury and Lawrence Summers find higher productivity growth is associated with higher average and median compensation growth. They use the median wage and the average wage of production and non-supervisory employees, as well as the average wage of all workers. In order to smooth out the up and downs of the business cycle, they calculate the three-year moving average of the change in inflation-adjusted compensation and labor productivity. Their findings (bold by me):

We find substantial evidence of linkage between productivity and compensation: over 1973-2016, one percentage point higher productivity growth has been associated with 0.7 to 1 percentage points higher median and average compensation growth and with 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points higher production/nonsupervisory compensation growth. … Our results suggest that productivity growth still matters substantially for middle income Americans.

Moreover, boosting productivity growth is at least as good for workers as reducing inequality. Stansbury and Summers note that if inequality had stayed at 1973 levels, the median worker’s pay would have been around 33 percent higher in 2016. But if productivity growth had been as fast over 1973–2016 as it was over 1949–1973 — about twice as high — median and mean compensation would have been around 41 percent higher. (Recall that the supposed “golden age” for American workers in the immediate postwar decades was also a time of rapid productivity growth.) S&S:

These point estimates suggest that that the potential effect of raising productivity growth on the average American’s pay may be as great as the effect of policies to reverse trends in income inequality. Conversely they suggest that a continued productivity slowdown should be a major concern for those hoping for increases in real compensation for middle income workers.

Productivity growth still matters for take-home pay

Likewise, the slowdown in productivity growth also provides a large part of the explanation of slow wage growth in the late 2010s — that, even though unemployment was even lower than what it was in the fast–wage growth era of the 1990s. The problem: Productivity growth has been rising only a quarter as fast as back then.

As economist Jason Furman wrote for Vox in 2019, it’s no mystery as to why wage growth was so fast in the late 1990s, but less so in the years leading up to the pandemic. Furman points out that productivity growth back then rose at a spectacular 3 percent annually versus just 0.7 percent annually more recently. Furman: “That’s part of the explanation for slow wage growth: Based on the productivity numbers alone, one would predict that average wages would be growing about 2.3 percent more slowly than they did in the late 1990s.”

And let me highlight this from Furman (bold by me): “Greater productivity growth holds the potential of being the most powerful source of sustained wage growth across the income spectrum.” (I like that so much, I might start using it instead of the famous Paul Krugman quote, “Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.”)

Thinking that productivity doesn’t matter or is a mere secondary or tertiary factor is why I use the word “pernicious” in the headline. Misunderstanding the continued value of productivity growing means misunderstanding the foundation of modern prosperity.

To (almost) conclude: Faster productivity growth is superimportant for faster rising living standards. And the sort of scientific discovery, technological invention, and commercial innovation that boosts take-home pay will also accomplish a lot of other pretty important things: increased opportunity, less poverty, healthier lives, a more stable climate, a multi-planetary civilization. I hope that’s one lesson we’ve all drawn from the rapid mRNA vaccine development over the past two years."

Saturday, February 12, 2022

The productivity-pay 'gap': a pernicious economic myth

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.