"Regardless of where you might live around the world, if you live on less than $2 a day, you would be considered to be living in extreme poverty.

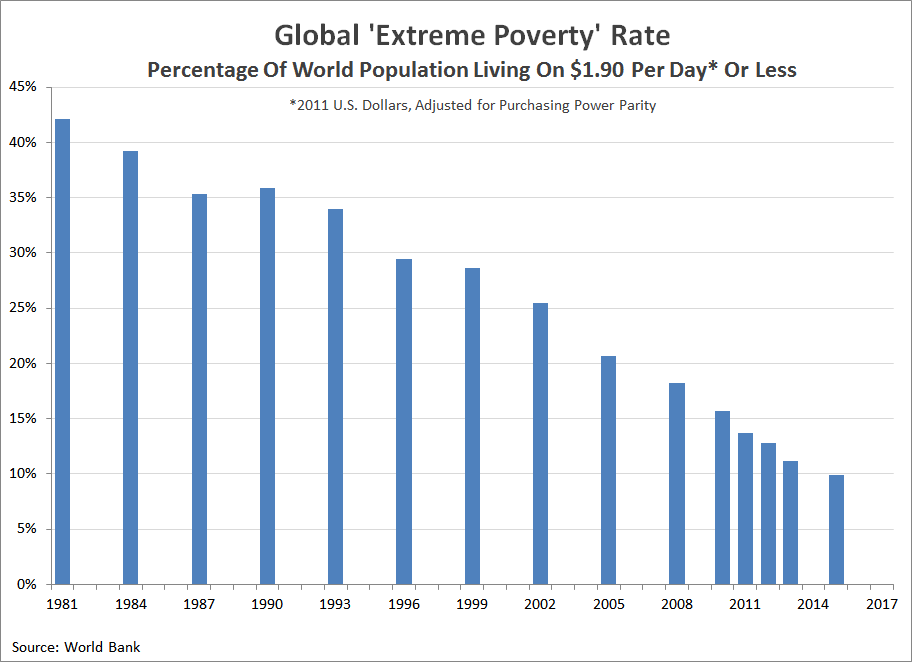

According to the World Bank, in 2015 about 736 million people around the world, or just under 10 percent of the world’s population, had incomes that put them below this international poverty line. Believe it or not, that is extraordinarily good news because poverty rates around the world have fallen dramatically since 1981 when 42 percent of the world’s population lived on an inflation-adjusted $1.90 or less per day.

World Bank economists studying a portion of this decline in the nine years from 2005 through 2013, when the extreme poverty rate was cut nearly in half from 21 percent to 11 percent, have discovered that much of this reduction in global poverty came about because of deregulation, as governments around the world have been reducing the regulatory burdens they impose on their citizens.

Using panel data for 189 economies from 2005 to 2013, this paper shows that business-friendly regulations are correlated with the poverty headcount at the country level. This association is significant using the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators on getting credit and contract enforcement. The findings suggest that the conduit for poverty reduction is business creation, as a source of new jobs and a manifestation of thriving entrepreneurship.Regulations can restrict the ability of individuals to find jobs or start businesses because politicians and bureaucrats often write them to benefit the interests of large, established interests, who would rather not have to compete for business in a free market.

This crony socialism benefits these special interests in two ways. First, by using the power of government to impose disproportionately large costs upon their smaller, less politically connected competition, they can keep their smaller competitors from being able to effectively challenge their interests.

Second, in the reduced competition environment that government regulation fosters, they can charge higher prices than they otherwise could, where they only need to provide the politicians and bureaucrats who write the rules a small cut of the action so they can fund their political campaigns to stay in power. Never mind the effect that has on the cost of living in the regimes where the regulations hold sway or the trust that people have in their political and economic institutions.

Historically in much of the world, the yoke of regulatory burden has contributed to the impoverishment of billions. Reducing that burden by lifting the heavy hand of government regulation has successfully diminished extreme poverty around the world in recent decades. It’s a lesson that everyone should learn."

"Every presidential candidate promises to “reduce income inequality” by raising tax rates on the rich and increasing transfer payments (including tax credits and in-kind benefits) for the middle class. Yet the widely-used flawed data from Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez exclude both taxes and transfers. Income measures that exclude taxes and transfers cannot tell us whether taxes or transfers are high or low, and cannot be directly affected by higher taxes on some or higher transfers to others (because such policies are ignored in the data).

A simple table adapted from the 2017 Consumer Expenditure Survey, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, may be sufficient to show how crucial it is to take account of taxes (including refundable tax credits), and also to adjust average income for the different number of people and workers per household.

Incomes are shown by fifths (“quintiles”), with the lowest 20% on the left and highest on the right.

The second row shows the “lower limit” of pretax income needed to counted be in each quintile.

The next two rows show mean (average) income before and after taxes.

The column at the far right shows a ratio of highest to lowest income, called the 80/20 ratio, which a common gauge of inequality. It shows that the highest 20% earned 16.5 times as much as the lowest 20% before taxes, but only 12.5 times as much after taxes.

But simply adjusting household income for taxes is not enough. Average incomes cannot be properly compared between the highest and lowest quintiles because there are three times as many people per consumer unit (household) in the highest 20% as there are in the lowest. And there are four times as many workers in the highest 20% as there are in the lowest.

By adjusting for different household size, we find the highest 20% earned only 6.5 times as much after-tax income per person as the lowest 20%.

But income is likely to be higher in households with two or more workers than it is in households with no workers or only one. So, that last row measures average after-tax income per worker in the highest and lowest quintiles (and those in between).

By further adjusting for the different number of earners, the highest 20% earned only 3 times per worker as much as the lowest 20%, after taxes.

Properly understood, the facts about U.S. after-tax income distribution and growth are insufficiently alarming to justify the political misuse of questionable pretax, pretransfer income statistics as a false argument for redistributing after-tax income."