"Over the past few years, Anne Case and Angus Deaton have unleashed upon the world a powerful meme that seems to link together America’s troublingly bad life expectancy outcomes with a number of salient social and political trends like the unexpected rise of Donald Trump.

Their “deaths of despair” narrative linking declining life expectancy to populist-right politics and to profound social and economic decay has proven to be extremely powerful. But their analysis suffers from fundamental statistical flaws that critics have been pointing out for years and that Case and Deaton just keep blustering through as if the objections don’t matter. Beyond that, they are operating within the confines of a construct — “despair” — that has little evidentiary basis. The rise in deaths of despair turns out to overwhelmingly be a rise in opioid overdoses. This increase is not happening in European countries that have not only been buffeted by the same broad economic trends as the United States, but are also seeing the rise of right-populist backlash politics.

The obvious explanation is that the US and Europe have very different laws governing pharmaceutical marketing.

That’s why the invention of supposedly-but-not-really safe time-release prescription opioids have wreaked havoc in the United States but not in Europe. Meanwhile, the same right-populist backlash occurs on both sides of the Atlantic because right-populist backlash politics is about the rising salience of conflict over post-material values like cosmopolitanism versus nationalism and has nothing to do with opioids or despair.

This is all actually pretty clear cut and has been said before, but critics must not be saying it clearly (or rudely) enough because the narrative just keeps trundling forward.

“Deaths of despair” 1.0

The first iteration of this narrative came in 2015 with the publication of Case and Deaton’s “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century.”

This piece is built around the observation that the death rate had been rising for white, non-elderly Americans, a change they said “was largely accounted for by increasing death rates from drug and alcohol poisonings, suicide, and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis.” They then aggregated deaths from those causes together under the banner of “deaths of despair” and argued that the increase in deaths of despair was evidence of a rise in despair, which they claimed was linked to broad social and economic trends.

You can see right here in this graph from their paper that the increase in overdoses (“poisonings” in the official death count) is dramatically larger than the increase in suicides and liver diseases.

They choose to interpret this as a sign of broad socio-cultural distress caused by declining economic fortunes:

Although the epidemic of pain, suicide, and drug overdoses preceded the financial crisis, ties to economic insecurity are possible. After the productivity slowdown in the early 1970s, and with widening income inequality, many of the baby-boom generation are the first to find, in midlife, that they will not be better off than were their parents. Growth in real median earnings has been slow for this group, especially those with only a high school education. However, the productivity slowdown is common to many rich countries, some of which have seen even slower growth in median earnings than the United States, yet none have had the same mortality experience. The United States has moved primarily to defined-contribution pension plans with associated stock market risk, whereas, in Europe, defined-benefit pensions are still the norm. Future financial insecurity may weigh more heavily on US workers, if they perceive stock market risk harder to manage than earnings risk, or if they have contributed inadequately to defined-contribution plans.

Note the extraordinary leaps of logic in this paragraph. They attribute the rising death rate among middle-aged white Americans to economic insecurity even though:

There was no similar increase in death rates in European countries, including those that had worse economic conditions.

The rise in deaths began before the economic problems.

Black and Hispanic Americans who lived through the same economic conditions didn’t experience the same mortality trends.

They acknowledge these catastrophic, fatal flaws in their own text, hand-waving them away with a reference to defined-benefit pensions. Nonetheless, both Paul Krugman and Ross Douthat seemed very impressed by the paper.

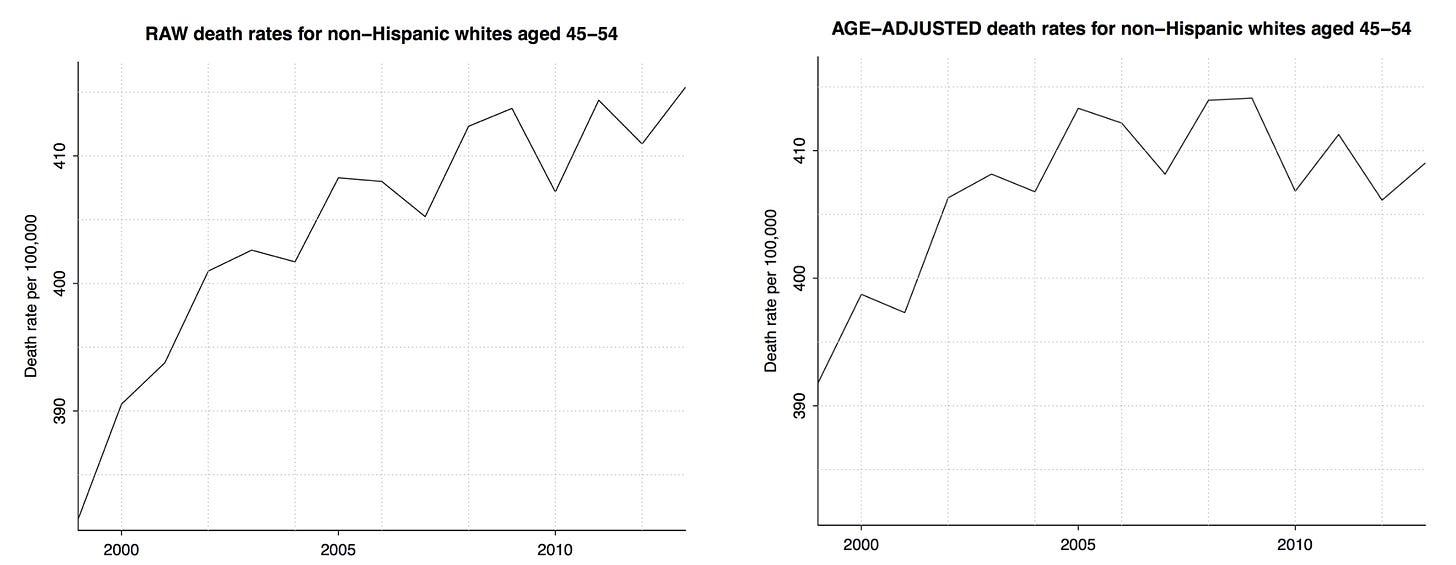

Meanwhile, Andrew Gelman noted on his blog that the statistical trend Case and Deaton were writing about is somewhat fake. Older people have higher death rates than younger people. And if you look at, say, the 45-54 age group during the time period that Case and Deaton are interested in, the average age of people inside that cohort rose during the 1999-2013 period. So if you use age-adjusted death rates rather than arbitrary binning, you get an increase that looks much less impressive.

Gelman concludes by saying “Let me emphasize that this is all in no way a ‘debunking’ of the Case and Deaton paper. Their main result is the comparison to other countries, and that holds up just fine.” Thus beginning the trend of people perhaps being too polite about this and letting a confused meme out into the world. After all, the fact that the increase in deaths was unique to the United States cuts against the thesis that it is tied to deep economic trends. And while the observation that the United States was experiencing a globally unique rise in opioid overdoses is true and important, there was and is no mystery as to why that happened here and not elsewhere.

Continuing waves of despair

In 2017, after Donald Trump’s election, Case and Deaton put forward a new version of the argument that didn’t address these concerns but did highlight that the “despair” is concentrated in non-college whites. Since non-college whites were also the key swing group in 2016, the idea that they were suffering from a massive wave of “despair” seemed politically relevant and revelatory.

But as Charles Lehman wrote in 2019, there was no evidence of a unitary plague of despair.

The trends in suicide and drug overdoses had different time series and different demographic patterns. What’s more, while the original Case-Deaton paper stopped its analysis in 2013, a time when the labor market was genuinely very bad, none of these trends have improved in the subsequent five years, even though the labor market got a lot better. I think it continues to be unclear why suicide rates have risen during this period, but numerically, the increase in drug overdose deaths was much larger. And while I wouldn’t say all the dynamics of the opioid epidemic are perfectly understood, the basic pattern of compounding supply shocks — first oxycontin, then fentanyl — is actually pretty clear. And looking at supply-side drug issues does a better job than “despair” of explaining both the cross-sectional (why just America) and time-series (why it kept getting worse) aspects of the puzzle.

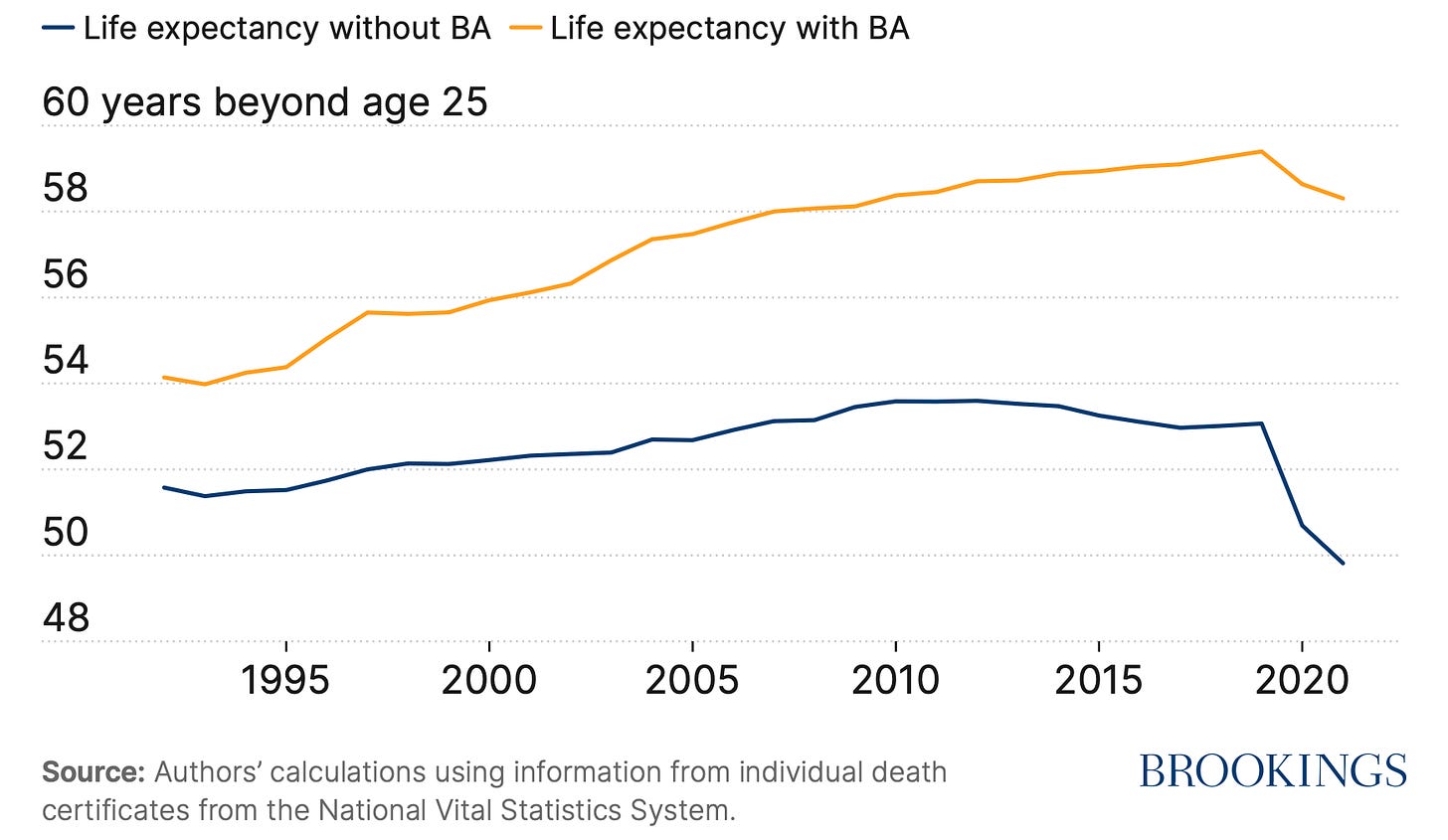

This year they have a new paper that drops the whites-only angle to focus exclusively on the degree divide and features this headline chart:

The extent to which they pull a switcheroo on race here strikes me as bizarre since previously the specificity of the non-Hispanic white piece of this was supposedly playing an important role in the analysis. But including people of all races makes the 2020-2021 drop look much more dramatic because the increase in homicides that occurred over those two years involved mostly Black and Hispanic victims.

More broadly, “despair” is no longer nearly as significant to the story. Since Case and Deaton are now concerned with long-term divergence, non-despair deaths now become very significant. Death rates for cancer and cardiovascular disease are falling for both groups, but they are falling faster for people with BAs. Death rates for respiratory diseases and “despair” (i.e., drug overdoses) are rising for both groups, but rising more slowly for people with BAs. Then we have the 2020-specific divergence, which we know pretty clearly is driven by Covid (there’s an education gap in remote work) and murder. For me, the facts that the once-central despair theme is now gone and the once-central race theme is also now gone call into question what we’re even doing here.

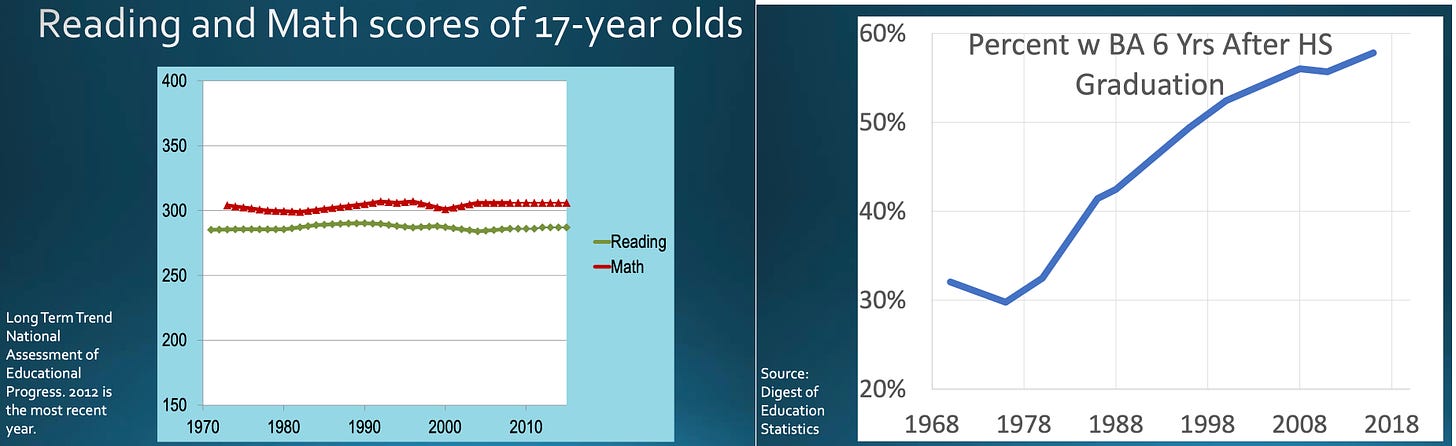

But whatever we’re talking about, as Caroline Hoxby notes in her comments, it seems to be mostly a selection effect. People without a BA are a smaller, more negatively selected group than they used to be — a group increasingly composed of low-conscientiousness people.

You sometimes see this mistake in the opposite direction. I remember a time when Twitter was going nuts over the finding that college graduates’ average WORDSUM score has fallen since the 1970s. But that doesn’t mean there’s a fixed pool of college grads and they are getting dumber; it means that a larger share of people are going to college. It is harder work, statistically, but what you really want to do is ask questions like “how are people in the top third of the education distribution doing vs people in the middle vs people in the bottom.” And as it turns out, Paul Novosad, Charlie Rafkin, and Sam Asher did just that last year in research Case and Deaton brushed aside.

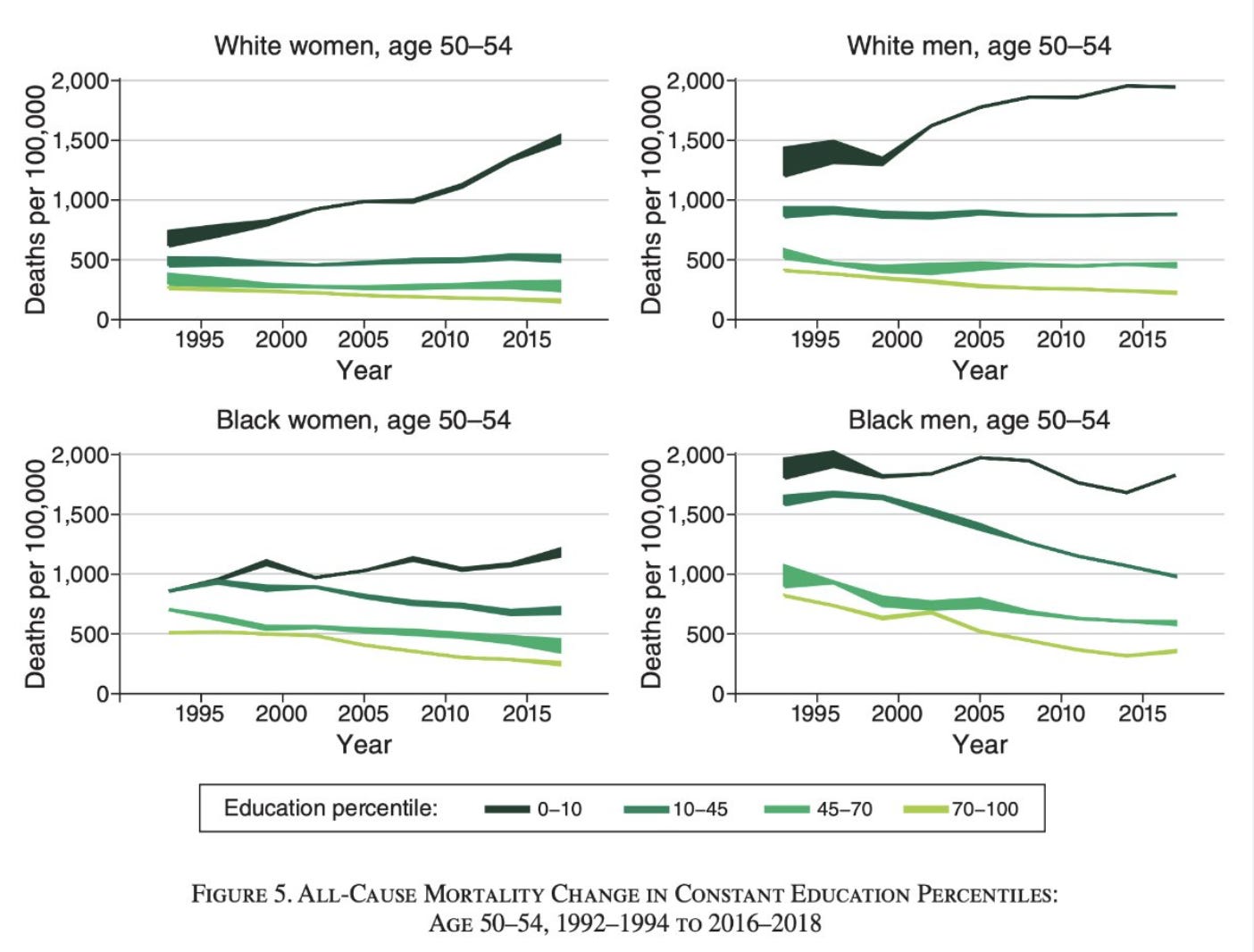

The bottom tenth is doing badly

Dylan Matthews wrote this up for Vox last week, but suffice it to say that when you account for compositional changes, you get a very different story. Instead of an educated elite pulling ahead of the working class majority, you see the bottom ten percent falling behind the rest of society. In the case of white people, that means the outcomes for the worst-off are getting worse, while the outcomes for everyone else stayed flat. For African-Americans, it’s more like the worst-off stayed flat and the rest saw improvements. This data ends before the Covid/murder death wave of 2020-2021, which may change things somewhat, but fortunately those trends are now reversing so this long-term trend is more important.

Matthews writes that “Case and Deaton in their latest piece describe this as confirmation that the ‘qualitative’ takeaway from their research is correct. I’m not sure I’d be that generous.”

I agree with him and, again, want to be a little less polite. Novosad, Rafkin, and Asher have provided a compelling analysis of a very concentrated problem of worsening health outcomes for the worst-off Americans. Case and Deaton, by contrast, have delivered a very misleading portrait of worsening health outcomes for the majority of Americans that (because they mistakenly think it’s a majority) they attribute to broad economic forces that exist internationally but which for some reason only cause “despair” in the United States. And then it gets worse, because as Matthews argues (citing Raj Chetty’s Opportunity Insights Project data), the growing disparities are located in specific parts of the country:

While it’s true that rich people in America live significantly longer than poor people, that’s much less true in New York City. It’s not true in California as a whole. Heavily urban areas with high education levels see a modest relationship between income and death rates. More-rural, less-educated areas, by contrast, see a very strong relationship between the two.

Areas with smaller mortality gaps tend to be places, the researchers find, with lower rates of smoking and higher rates of exercise, which makes sense when you consider that the variation in death rates between cities is driven not by factors like car crashes or suicide but conditions like heart disease and cancer, which are themselves driven in part by lifestyle conditions. Local unemployment rates and other indicators of the health of the local labor market did not seem to be associated with longevity, nor did income inequality. These aren’t firmly causal findings, to be clear, but they might be suggestive of potential causes to investigate.

Conveniently, there’s a new piece out in the Washington Post by Lauren Weber, Dan Diamond, and Dan Keating that I think explains this geographic variation very well: Places that adopt nanny state policies to improve public health get better public health.

They look at state border effects around the shores of Lake Erie, where you can find Ashtabula County, Ohio right next to Erie County, Pennsylvania and Chautauqua County, New York. These are similar places that are subjected to very different state policy regimes. The authors note that Ohio, though under firm Republican control, has a somewhat moderate governor who has pushed the legislature for stricter seat belt laws and higher tobacco taxes, but the legislature doesn’t agree with him. Not surprisingly, Ohio has higher rates of smoking-related deaths and worse automobile safety. People are obviously within their rights to disagree about this stuff, but it’s fairly straightforward.

If you decide to implement paternalistic health policies, you get better health outcomes; if you don’t, you don’t.

Leaving despair behind

Life expectancy is a complicated statistical construct. And lots of different trends influence death rates. There turns out to not be a simple one sentence explanation for why American death rates have risen in recent years or diverged in certain populations, and it can be annoying to keep track of the distinction between rates and levels and who exactly we are comparing to whom.

Over the past two years we’ve seen a divergence in Covid death rates due to different levels of vaccine uptake. That will show up as more deaths in red states than in blue ones, but also within states, you will see more deaths of Republicans than of Democrats. Because Republicans and Democrats have different demographic characteristics, a person who’s not paying attention to what’s happening could end up characterizing this as a wave of deaths hitting white, rural, non-college people for mysterious quasi-spiritual reasons. But because we have all seen with our eyes the debates across society over whether you should take Covid vaccines, we should be aware that this is actually about Covid vaccines.

And so on down the list:

The increase in opioid deaths is about prescription drug policy and the rise of fentanyl.

The divergence in traditional public health outcomes is about the divergence in state public health policies.

The surge (and subsequent decline) of murders is about post-Floyd depolicing and people deciding that was a bad idea.

Knowing these analytic facts, of course, does not fully answer questions about public policy. The science of vaccines is a lot clearer than the social science of how to get people to take them without generating counterproductive backlash. We would have fewer suicides if there weren’t so many people with guns in the house, but the politics of achieving that is very challenging. On the other hand, while raising alcohol taxes seemed politically inconceivable a couple of years ago, with interest rates rising we need to do something about the budget deficit so maybe this goes back on the table.

The point is that we face a set of discrete public health challenges that we need to think about both as policy matters and in terms of politics and public opinion. But there is no “despair” construct driving any of this, and the linkage to big picture political trends is simply that Republicans are more hostile to regulation. Case and Deaton, meanwhile, have sent us on the equivalent of a years-long wild goose chase away from well-known ideas like “smoking is unhealthy” or “it would be good to find a way to get fewer people to use heroin.”"

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.