The best thing about the past is that things changed more rapidly

"Life has changed a lot over the last 60 years, and not every single change has been for the better. This periodically results in some version of this meme going viral:

The argument is essentially that the material living standards of the typical American family have gotten worse since the post-WWII era. This is completely wrong.

A contemporary American family not only has access to all kinds of technology that would have delighted and amazed people from 60 years ago (luggage with wheels, microwaves, surround sound, ciabatta), but we also consume much more housing, cars, and college education.

It’s bad to lie to people about this, both on general principle and because it obscures some plausible accounts of the ways in which some things have gotten worse. Most of all, though, the nostalgic orientation sows confusion about something fundamental: the pace of economic growth really was much faster in the 1950s and 1960s. Americans are richer today than they were two generations ago, but we are growing richer at a slower pace. That’s not ideal.

There is something to the fact that this poorer-but-faster-growing period is remembered fondly, but the right takeaway isn’t nostalgia for the past — it’s impatience with the current slow pace of growth.

People were poor in 1960

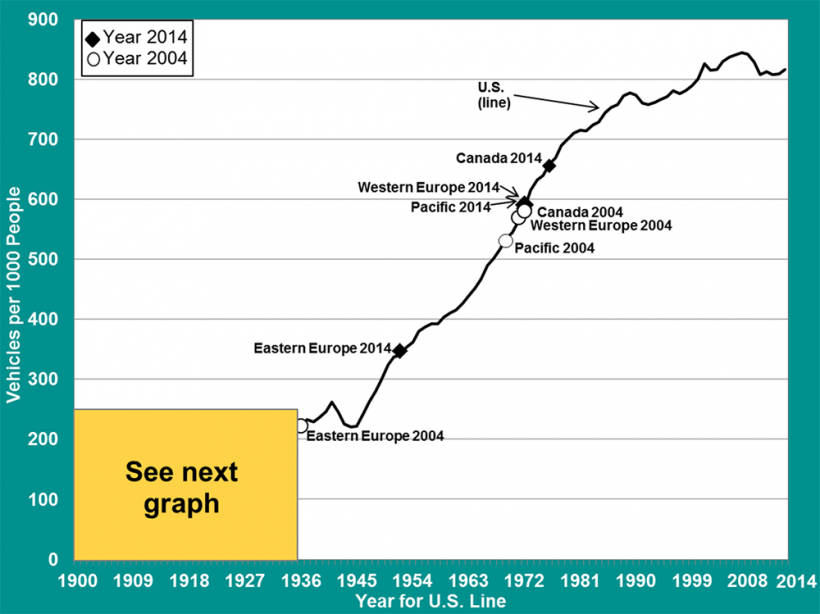

In 1960, there were roughly 400 vehicles per 1,000 Americans, about half of today’s car ownership rate. In other words, a family in 1960 could afford a car on one income, but today they would have two cars.

The average new house built in 1960 was about 25% smaller than a contemporary house, and much worse provisioned in terms of amenities like dishwashers, clothes dryers, and fireplaces.

Of course those were new houses. Many people in 1960 lived in older buildings that often lacked amenities that are now ubiquitous — you can read about cold water flats in New York that had no hot water.

And lots of people were living in rural poverty in extremely old structures.Overall, running water was about as common in 1950 as home air conditioning is today. Dishwashers and washing machines were rare luxuries.

Broadly speaking, if you think about how American life has changed, the striking thing isn’t how much people used to be able to afford on one income, it’s how much easier it is today to get by with just one adult in a household. If you hear about a single mom who owns a car, your first thought isn’t “wow, she must have won the lottery.” Doing laundry and folding clothing with modern appliances is annoying, but objectively much less time-consuming than it was in the poorer past.

Americans have become better-educated

The college point is more subtle because college really was cheaper in the past.

And there were two aspects to this.

One is that colleges themselves spent less money per student. The administrative staffs were smaller. There was no IT team maintaining the campus-wide WiFi network. I think reasonable people can disagree about the merits of some of the “extras” that are included in a contemporary college education bundle, but there clearly is more stuff. Not all of it has obvious educational value. All the IT expenditures, for example, almost certainly have very little impact in terms of improving students’ education, but it’s also inconceivable that a college campus would just refuse to create and maintain on-campus internet access. Nobody would want to attend or teach at a school like that.

The other is that college has become less subsidized over time. Medicaid didn’t exist until the mid-1960s and it covered very few people in the early days. Over time, it has become a bigger and bigger item on state budgets, and they’ve compensated in part by reducing higher education subsidies. The federal government has stepped in to fill part of the gap with the student loan program, but that’s a less generous subsidy.

And given the availability of less expensive higher education, it’s really striking how much less educated overall the population was at that time.

This is relevant for two reasons. One is that the social calculus that student loans were a “good enough” form of subsidy to continue expanding access to higher education was correct. You don’t need to love the student loan system, but it is true that qualified students are generally able to attend college in the United States regardless of ability to pay and that for those who graduate from reputable institutions, it’s worth their while.

But the other thing is that it’s much cheaper to subsidize college education when you don’t have so many people going to college! Back in 1960, only 45% of high school completers attended college versus about 60% today. That itself understates the change because the high school completion rate has risen by about 10 percentage points since then. If you eliminated one-third of the college students, that would free up lots of extra subsidies for the remainder. But I’m not sure that would be a change for the better.

At any rate, it’s definitely not the case that the typical family 60 years ago was sending their kids to college on one income, because most kids didn’t go to college.

Some things have changed for the worse

None of this is to say that life has gotten better in all respects. The technology for manufacturing and distributing opioids has improved dramatically, for example, which is a kind of progress — but it’s bad.

We also have a certain amount of what I think we should probably see as problems of affluence. I read a funny study recently that looked at Swedish lottery winners. It showed that when single men win the lottery, they are more likely to get married. But when married women win the lottery, their odds of a short-term (but not long-term) divorce rise. Somewhat along these lines, I think because people in general are richer and because women in particular have dramatically higher earnings potential than they did 60 years ago, you see more single parents than we used to. This is downstream of material prosperity — mothers are less economically dependent than they used to be — but I think it’s probably not ideal for kids’ social and emotional development.

We have less malnutrition and a lower incidence of people being underweight than we used to, which is good, but we now have a large and growing obesity problem that I think is mostly a consequence of more food availability. People sometimes argue that healthy eating is more expensive, but this really doesn’t check out. Material abundance in the realm of food just turns out to have downsides.

There are also some specific areas where public policy has made things worse. The average home size has gotten larger because we’re richer. But we’ve also taken a lot of regulatory steps to ban what used to be the lowest end of the housing market. As a result, people who in 1960 might have lived in a rooming house or an SRO now tend to end up in a homeless shelter or on the street. This doesn’t directly impact the average person, but it has the indirect consequence of creating the temptation to use mass transit systems and other public facilities as de facto shelters, which thereby degrades the experience for everyone.

But mostly I think it’s important to be clear that if what you’re regretting is the demise of 1950s family dynamics, you are regretting the consequences of prosperity. If you want to have a two-parent, one-income family in a 1950s-sized house with one car and not send your kids to college, you can almost certainly afford that. Indeed, the stay-at-home mom will spare you the costs of childcare, summer camp, and other things that genuinely have gotten more expensive as a result of rising wages. And you’d even be able to take advantage of modern advances like Netflix, out-of-season fruit, and affordable domestic airfare. That’s just not the life most people choose.

The future ain’t what it used to be

As I mentioned at the top, where I think there’s some legitimate grounds for nostalgia is that while Americans in the 1950s and 1960s were much poorer than in the 2010s or 2020s, the rate of economic growth was faster. Fast growth meant a broad sense of social mobility—not just a shuffling of people in the class hierarchy but a very large share of the population growing up to be dramatically richer than their parents.

But American growth took a big blow during the energy crises of the 1970s, which was probably unavoidable. What happened after that, though, was a series of self-inflicted wounds.

The rapid growth of “the good old days” meant that, in a literal sense, things were changing a lot with tons of new stuff getting built — because that’s what happens when a society experiences rapid economic growth. New technology is deployed, physically, in space. The built environment alters as physical capital is accumulated. And if a bunch of people build a bunch of stuff in a bunch of different places over an extended period of time, there are basically two options:

All the planning and execution can be done by flawless superheroes who never make an error of judgment, never experience blind spots, and are impervious to corruption.

Some of the stuff that gets built turns out to be a bad idea.

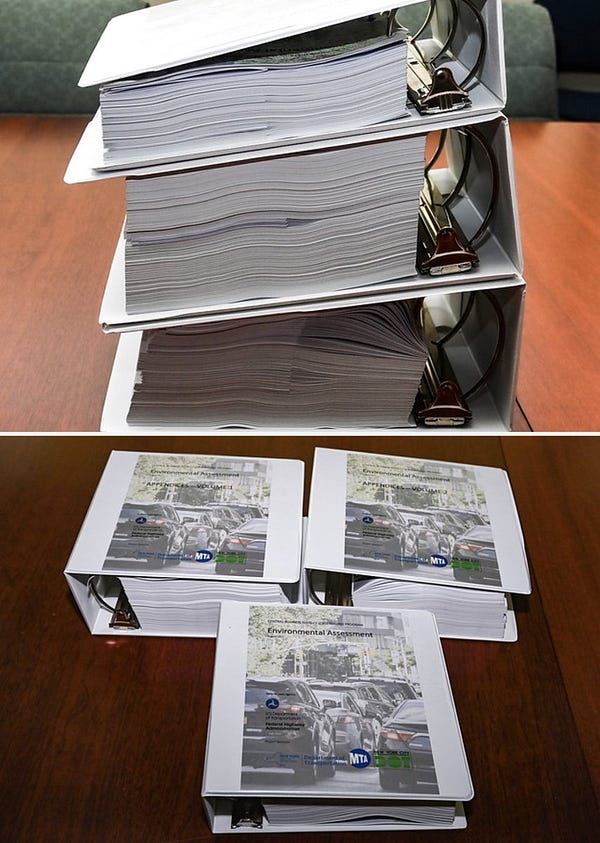

Since the United States of America is populated by human beings, we got (2) rather than (1). But the social reaction to this wasn’t just to write laws like the Clean Air Act that require people to take pollution externalities into account when they burn stuff. We also implemented things like NEPA review, where the premise is basically that any deviation from the status quo is inherently suspect and therefore something like a congestion pricing plan for Manhattan should require a three-year, 4000-page environmental review.

Congestion pricing in NYC is the perfect case study of what’s wrong with NEPA. This is the 4,007-page environmental assessment that took 3 years to produce even though the state legislature approved congestion pricing in 2019. Thread (1/13)But this is very much not unique to NEPA. The premise of historic preservation policies in the United States is that old stuff is per se better. The land use regime in essentially every jurisdiction puts a thumb on the scales against adding more buildings on the premise that building more stuff is bad.

Living standards still inch forward under this regime, but it’s concentrated in computer and media, things that can be achieved almost entirely through the diffusion of information. There was a time a few years back when we had an explosive diffusion of ramen shops, and you can now get a pretty good bowl of tonkatsu in all kinds of places. Right now something similar is happening with Nashville hot chicken and Detroit-style pizza. But we could have much more rapid change if we wanted to, and that would let us recapture some of what was legitimately great about this earlier era in our history. But that requires letting go of nostalgia and embracing dynamism.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.