by Guy Rolnik at Pro Market blog.

"Looking at both intangible investments and political activities to explain the 20 percent rise in Tobin’s q in

the U.S. since 1970, a new working paper by James Bessen from Boston

University concludes that activity associated with increased federal

regulation is the most important explanatory factor, especially after

2000. In fact, spending on R&D and other intangibles has fallen,

relative to conventional assets, since 2000.

Noting that operating margins for these

firms have also risen since 1990 by over 2 percent in aggregate,

Bessen’s study also found that variables associated with regulation and

corporate campaign contributions account for about half of this

increase.

When expressing the political rent

seeking effect in dollar terms, the paper states that it corresponds to

an increase in the value of non-financial public corporations of about

$2 trillion, and that this amounts to an annual transfer from consumers

to firms of about $200 billion. Several tests performed by Bessen also

suggest that the link between industry regulation and corporate profits

is indeed causal, flowing from regulation to profits.

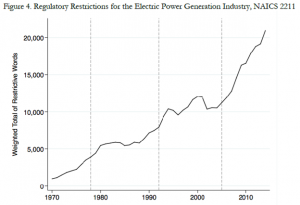

The RegData technique provides deep

insight into the complexity of regulation. For example, last January,

the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, which hosts the RegData

project, published “The McLaughlin-Sherouse List: The 10 Most-Regulated Industries of 2014,”which

was led by petroleum and coal products manufacturing (25,482

restrictive words), electrical power generation, transmission and

distribution (20,959 restrictive words), and motor vehicle manufacturing

(16,757 restrictive words). Bessen used RegData

to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between regulation,

rent seeking and the balance of power between corporations and

consumers.

Bessen’s paper corresponds with a 2015 presentation by Jason Furman and Peter Orszag,

in which they explored the potential role of rents in the rise in

inequality, and in allowing firms to achieve super-normal returns. After

comparing the distribution of returns on equity across S&P 500

firms between 1996 and 2014, they found a distinct possibility of “an

increased prevalence of super-normal returns over time” (which the

distribution skewed to the high-end over time, since the firm at the

high-end of the distribution earn more super-normal returns). After

reviewing Census Bureau data on market consolidation showing that in

three quarters of the industry covered by the census, the 50 largest

firms have experienced a rise in revenue share, the two concluded that

“consolidation may be contributing to the changing distribution of

capital returns and the increased share of firms with apparently

super-normal returns.”

Bessen’s path to his current academic post, a lecturer at the Boston University School of Law, was unusual.

Bessen studied economics at Harvard.

Later he became a software engineer and developed the first commercially

successful “what-you-see-is-what-you-get” (WYSIWYG) PC publishing

program. In 1993 he sold the company he founded, Bestinfo. He returned

to academia, working with Nobel Laureate Eric Maskin on a paper about

software patents. In 2002 he became a visiting scholar at MIT’s Sloan

School of Management, and in 2004 he joined Boston University.

James Bessen: My main research

focus is technology. I have a technology background. I ran a software

company and it’s what I have been studying for about 15 to 20 years.

This is my second piece on political economy. The first was that Foreign

Affairs piece.

As I was looking at what was happening in

technology policy across many different areas, I saw the same thing

happening, whether you are talking about trade secret law, patents,

non-compete agreements for employees, or government procurement policy.

It just seems that policy is working against startups in way not seen in

the past. It seemed to be in favor of the incumbent firms. That

observation led me to the Foreign Affairs piece.

GR: Did it come from your academic work, or was it something that you picked up when you were still in industry?

JB: It came more from the academic

work. A lot of my work was in the area of patents. When I was in

industry, I was in the software business. Just after I sold my company,

they started issuing software patents in large numbers. Immediately,

people in the software industry were upset by this.

They felt that, “Here’s a very innovative

industry. Why do you want to introduce patents and lawyers into

something that’s working very well without them?” To this day, most

software developers are opposed to patents on software, or at least most

patents on software.

I started a line of research that looked

at that controversy. What happened was, it turned out that it was the

well-established hardware companies, and then later on, the large

software companies, were in favor of these patents, but most software

developers were not.

Even as recently as four or five years ago, start-up firms generally didn’t get patents in software.

These patents benefit large hardware and

software companies, sometimes at the expense of startups. But because

this change created large numbers of software patents with poorly

defined property boundaries, patent litigation started to increase

sharply. Many of these lawsuits were filed by patent trolls who used

lawsuits to extract settlement payments from startups.

As we did more empirical research on what

was going on with patents and patent trolls, and it became a

legislative issue, it was very striking.

We did a lot of work on patent trolls

that was entered into the debate as firms were pushing for legislative

reform on patents. The lobbying that went on was so striking. It was

huge. It was an education for me.

Where I’d been thinking in very academic

terms, there is this brutal policy landscape and conflict that goes on.

That has a whole lot to do with how this policy has evolved in the

beginning and how it is evolving today.

GR: When you say it was an

educating experience for you, do you mean that you realized that

regulation and patents work for the big incumbents?

JB: Right. Not only do they work for them, but that the political process was centered around them.

I’ll give you a little backstory. There

was a lot of discontent that started bubbling up in the late 2000s, a

huge increase in lawsuits.

Lots of small companies were sued both in

tech fields and even outside of tech. A lot of retailers, a lot of

travel or hotel industry people, who all of a sudden are upset about

patents because they’re getting sued over this whole range of patents

that should never have been issued, but it becomes a legal strategy to

extract money out of them.

In 2011 a new patent law passed, the

Leahy-Smith America Invents Act. This patent law was essentially

negotiated between a small number of large pharma companies and a small

number of large tech companies.

This law has some good things about it,

but there was a huge amount of lobbying, a huge amount of money that

poured into this, and they came up with something that was very tame.

Because it didn’t address the problems,

all of a sudden you have a whole lot of small businesses in every state

in the country who are now upset about getting sued for patent

infringement over these very ridiculous claims.

What you saw from 2013 is this much

broader grassroots activity pushing for patent reform by a lot of

start-ups, by a lot of small companies, throughout the country.

It’s been pretty much blocked by

pharmaceutical companies, patent trial lawyers and some well-established

interests. This was my original education on how things are playing

out. It’s happening in other policy areas.

GR: What brought you to this recent paper?

JB: I’ve been reading some of the papers of Jason Furman and Peter Orszag.

GR: Do you mean the paper about the “super firms”?

These investments don’t show up in normal

accounting, in the normal balance sheet, as assets, and this has been a

well-known problem for some time. When I started out I had the

expectation that I was going to find that there were some political rent

seeking aspects to the rise in profits and the rise in corporate

valuations, but that it was probably more an issue of unmeasured

technology investments.

What I found was that I was wrong in my

prior opinion, especially for the last decade, it’s been more a story

about political rent, especially concentrated in regulated industries.

GR: How long was the period you’ve been looking at?

JB: The total period I looked at was from 1970 to 2014, but when I say, “The last decade,” I really mean from 2000 on. 2000—that

was when the tech bubble burst, the Internet bubble, and firms had been

spending a lot on technology. They cut back some of that spending.

Since then, you’ve seen a relative decrease in technology spending, but

regulation and campaign spending have gone up.

GR: Why do you think that lobbying expenditure is a good measure of rent seeking?

JB: I don’t think lobbying

expenditure itself is a very good measure. One of the things that comes

out of this paper is the suggestion that lobbying expenditure and

campaign spending are tip-of-the-iceberg measures.

What it finds is that the regulation index is the strongest factor.

GR: The RegData index.

JB: The RegData, yeah. That is

picking up. My interpretation is that when you see an industry with a

very high RegData index, a very high level of complexity or restrictive

words in the regulation, that reflects a lot of industry rent seeking

activity. But the nature of that activity is very varied and involves a

lot of different things.

It includes lobbying and campaign expenditure, but those two things are probably a small part of it.

GR: Is this a more of a Stiglerian phenomenon, or more of a tollbooth phenomenon?

JB: It’s very much a Stiglerian

type phenomenon. The tollbooth idea implies that regulators want to

extract rents from companies, and so you would expect highly regulated

industries to have decreased rents.

The Stiglerian idea is that regulation

comes about because of cooperation between regulators and industry, and

so you would see greater rents. That’s what we see. It may not be a

simple story of industry activity capturing individual regulators.

There may be a much more complex story.

It may be, for instance, that regulatory complexity helps established

firms extract rents and complexity serves as a barrier to entry to new

startups; these barriers can increase rents and corporate valuations.

GR: So the important empirical

evidence is derived from RegData correlating with the rents that are

manifested by the Tobin outcomes?

JB: Right. I’m seeing a large correlation, and that seems to be accounting for a very substantial part of the increase in rents.

It could be that we’re seeing a spurious

correlation and that perhaps it’s high-profit industries that are

attracting regulation.

At the turn of the 20th century, trusts

were these high rent, high monopoly industries that were getting

attacked by regulators because they were making high profits.

I did this causal analysis and found that

the causality really does flow the other way: when you see an increase

in regulation, profits follow.

GR: Another surprising finding of

yours is that you feel that most of the rents are derived from complex

regulations, and not from market power driven by concentration.

JB: I don’t think these things are

necessarily in opposition. The problem is that my data doesn’t speak to

it. I do use the share of the top four firms in an industry and find

that it does not have much explanatory power. But that’s only one

measurement of market power.

There may be many other sorts and it may

be that the relevant sorts of market power aren’t picked up by a simple

index like that. It may be that, for instance, when you think about the

electric utility industry, the relative market power is not the national

market but the local market, so you’re not going to pick it up there.

When you think about the pharmaceutical

industry, you may be talking about a highly differentiated product

market, so it’s not the number of pharmaceutical firms in general. It

may be the ones that are particularly involved in producing Statins, or

cancer drugs or other treatments.

There are these niche markets that they compete in and they may very well work as monopolies.

GR: Some of the industries

that you do mention that have rising regulatory complexity are also

quite concentrated or have high HHI values, like telecom, mobile, cable,

big pharma, and of course airlines, railways, and so on.

JB: That’s right. The study raises

more questions than it answers. These are some of the interesting

questions. What it speaks to is that we really don’t have our arms

around what’s going on in all these industries. We can speculate.

It’s this notion that we can look at

these concentration ratios, and they’re indicative for some industries,

but in other industries it’s not picking it up. It’s just not the best

measure.

GR: How is it that the financial sector does not appear among the five industries that you mentioned?

JB: Good question. It’s because the way that balance sheets are constructed and…

GR: Because of the Tobin’s measure, you can’t use Tobin

for financial companies. Since RegData is the base of your empirics, can

you say something about the way it works?

JB: It’s a very clever approach

they’ve got. They’re continuing to refine it. Previous measures have

just looked at the gross number of words in regulations. The developers

of RegData do two things. One is they look at restrictive words, words

like “shall,” or “must,” to rank the restrictiveness of each section of

the Federal Code. They also look at key words that relate to a

particular industry, using a sophisticated textual analysis, and that’s

where we get the real action in this case. They’re able to go and do an

annual measure, for most industries, that tells us the regulatory

complexity. It’s fascinating to look at some of these.

You see something like major legislation

gets passed—and then the regulatory complexity goes up. You see some

cases where there’s deregulation occasionally and the complexity goes

down for a period of time, but the overall trends are up.

GR: Would it be correct to say that, in a way, what

you’re saying is that this paper adds to the literature that proves that

George Stigler was right, and it’s happening in a big way in the last

15 years?

JB: Yes. The surprise here is the

magnitude of things. That’s what caught me and surprised me. I’m seeing a

very strong effect and an economically large effect. That makes me

stop, think and say “This is important stuff.” It’s Stigler being right

in a big way.

GR: In your HBR paper you say that basically lobbyists

and lobbyism are only the tip of the iceberg. Can you describe what you

think goes beneath the surface level in this?

JB: First of all, it’s not only

U.S. activity. It’s global. Second, lobbying is largely directed at

getting legislation and regulatory decisions, but there’s a lot of what

we would call rent seeking activity.

If you look at the electrical industry or

cable television, there are rates that get set. There are these complex

rules, and firms have to meet with regulators on an on-going basis.

That’s not lobbying, per se.

They may challenge those rates and those

rules in court. They need to be monitoring them. They may change their

offerings, their products, to take advantage of changes in regulation.

That was part of the story with the Cable Act of 1992 where they made

these changes.

This is the point that Richard Posner

made back in 1975. Using the example of airline regulations, he saw that

rent seeking involves actually changing the nature of their products

and services. You’ve also got activities like clinical drug trials which

are huge investments that pharmaceutical firms make with the aim of

getting regulatory approval.

All of these sorts of things are termed

as rent seeking activitis—activities where the firm invests in getting a

political outcome that increases their rent."