"Just how much do ill-constructed regulations cost the US economy? That’s one of the great economic unknowns.

In this context I found a very interesting tidbit from Mary O’Grady’s coverage of President Milei’s reforms in Argentina.

Argentina’s deregulation czar, Federico Sturzenegger…[has] discovered a rough rule of thumb: Where deregulation happens, prices decline in the range of 30%. He has seen it in textiles, logistics and some agricultural products.

Notoriously, removing rent controls in Buenos Aires has lowered rents by about the same amount. The supply expansion overwhelmed the actual price control.

A price decline of 30% tells us that the economic benefit of deregulation is at least 30% of current income. Real GDP is price times quantity, so even if the quantity of the deregulated good does not change, a 30% decline in prices gives people that much more real income to spend on other things. And it’s a lower bound. If rents, textiles, and logistics decline in price by 30%, rent-paying businesses, clothes makers, and everyone who sends something anywhere by truck can expand their businesses.

Even 30% is a lot. That’s a decade of 3% extra growth. That’s the difference between the US and most of Europe. That’s orders of magnitude more than most conventional economists will allow as the cost of regulation.

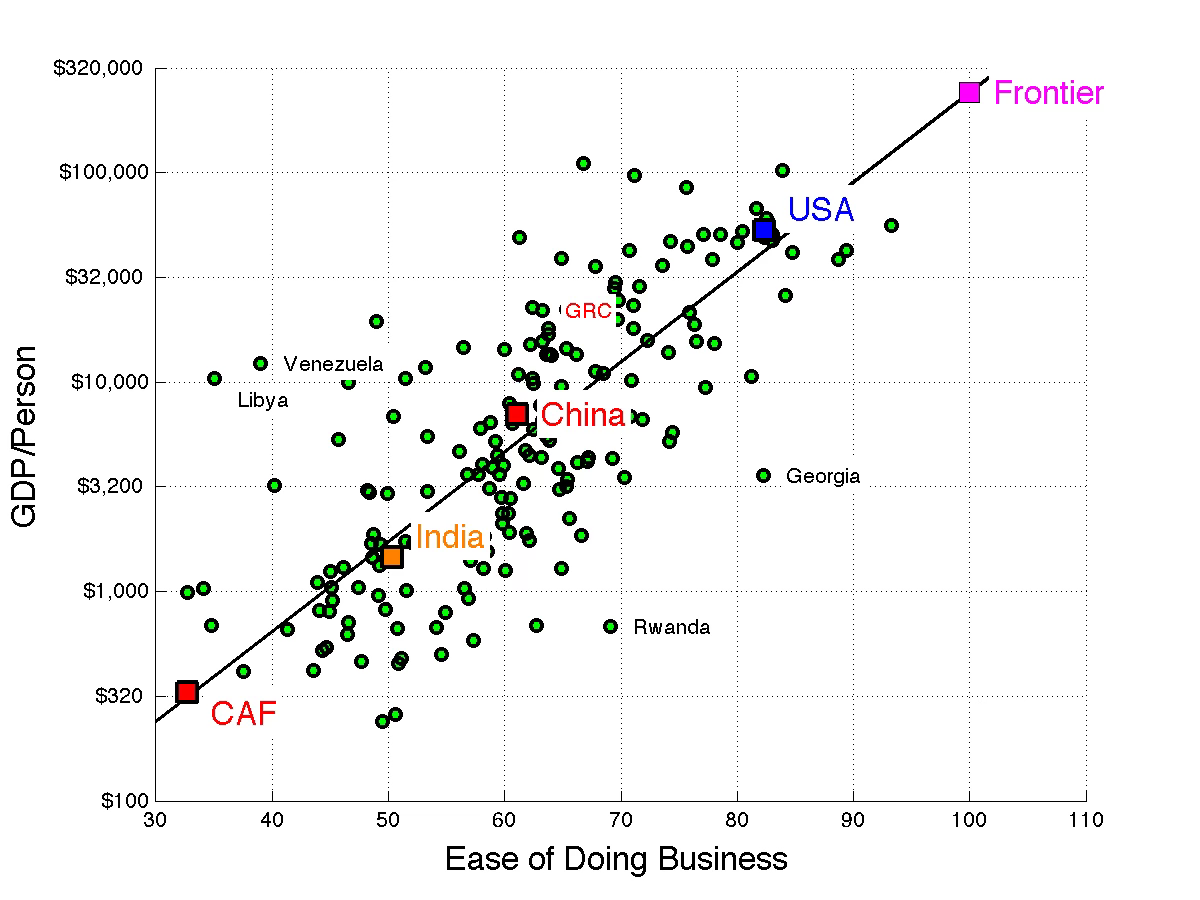

A while ago I wrote about regulation and growth, including this graph

This shows the correlation between the level of GDP per capita and the World Bank’s (then) ease of doing business measure. 100 is the best observed policy in each category, so is achievable. Not even the US is perfect. The regression line shows an eye-popping possibility for even the US to improve just by fixing the remaining impediments to business. I was pilloried, of course, for the suggestion.

O’Grady also relates

Price differentials between the international and domestic market are one measurement he uses to prioritize his agenda because wide variations often signal barriers to competition.

The US is already comparatively less regulated than other countries, so this approach is not as easy for us. Well, perhaps we should look at inexpensive Chinese imports, and instead of just screaming the usual “subsidy, unfair, overcapacity, currency manipulation, dog ate my homework” sorts of excuses, realize some of that reflects our regulatory roadblocks to getting anything done. (Some of those regulations are worth it, of course. But not all.) We can certainly look across states. California houses are expensive entirely due to regulation.

Why do economists not pay a lot more attention to smarter regulation? (I like to avoid “deregulation,” as regulation is not about pouring more in or less. It’s about a very hard job of writing smart rather than counterproductive regulations.) Well, like the famous drunk looking for his car keys under the lamp-post, not across the street where he dropped them, economists naturally focus on what we can measure. It’s very hard to measure the economic damage of regulations. It’s hard to see all the businesses products and services that might be there if regulation had not stifled them.

Many studies of regulation count up the number of regulations, or the paperwork time devoted to filling out forms. That’s a good start, but it’s obviously a scratch on the surface, a tip of the iceberg of economic damage. That we even bother with such measures lets you know how hard the real issue is. For example, housing construction is severely limited in California. That leads to sky-high prices, people who can’t take good jobs, and businesses who can’t find nearby workers. The cost of filling out the forms is considerable, but tiny compared to the economic damage.

Obviously, un my view if the DOGE can get off the ground its possibilities are a lot more than economists usually imagine."

Tuesday, December 17, 2024

The cost of regulation

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.