"It stuns me that the United States educational establishment tried to teach reading by thinking of words as pictures (whole word) or by literally using pictures to decode words (cueing). These are anti-conceptual methods and the result has been such a disaster that phonics is now being taught in high school in a (laudable) attempt to remediate.

NYTimes: In the early to mid-2010s, when high schoolers today were in elementary school, many schools practiced — and still practice — “balanced literacy,” which focuses on fostering a love of books and storytelling. Instruction may include some phonics, but also other strategies, like prompting children to use context clues — such as pictures — to guess words, a technique that has been heavily criticized for turning children away from the letters themselves.

…For some Oakhaven students, filling in gaps means going back to the beginning.

In an intensive class focused on phonics, ninth graders [AT] recently learned about adjacent consonants that make one sound, as in “rabbit,” and silent vowels. Students were mostly enthusiastic, competing to spell “repel” and giggling through an example about “dandruff.” After years of frustration, breakthroughs can feel exciting — and empowering.

One student said her grades had improved, and she was thinking about reading “The Vampire Diaries” novels, an undertaking, she said, that she previously would not have considered.

See my previous posts on Direct Instruction for more."

Saturday, December 31, 2022

Phonics in High School!

How Venture Capital Made the Future

Sebastian Mallaby's The Power Law explores how venture capital and public policy helped shape modern technology

"The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future, by Sebastian Mallaby, Penguin Press, 496 pages, $30

"Liberation capital," as investor Arthur Rock called it, "was about much more than keeping a team together in the place where its members happened to own houses." In 1957, Rock took a gamble on the "traitorous eight"—a team of promising engineers at Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory—and counseled them to free themselves of their authoritarian boss by quitting en masse and striking out to form Fairchild Semiconductor.

Rock was an amalgamation of consigliere and connector. He helped the group secure funding, cementing his place in history as the father of modern venture capital, which offered an alternative to stuffy East Coast financial institutions that were leery of lending to tech ventures they perceived as risky.

In The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future, journalist Sebastian Mallaby draws on interviews with scores of high-profile venture capitalists (V.C.s)—and other sorts of reporting, including four years of sitting in on firms' meetings—to tell the story of Rock's new paradigm: a form of financing that centers on funding high-risk, high-reward companies in their early days. Mallaby, who similarly embedded himself in the world of hedge funds when writing his 2010 book More Money Than God, smartly details the well-placed V.C. interventions that produced technologies too many industry critics take for granted today.

While detractors frequently downplay how much public policy can help or hinder innovation, Mallaby never neglects the subject. A reduction in the maximum individual capital gains tax rates in the late 1970s and early '80s—from 35 percent for most of the '70s to 20 percent by 1982—left venture capitalists flush with cash and eager to invest. Without these preconditions, Apple and Atari might not have flourished; Leonard Bosack and Sandy Lerner's Cisco, which pioneered multiprotocol routers, might not have received enough investment; and advances in computing might not have taken off at the time and speed that they did. As Silicon Valley competed with larger, more established investing firms in Boston and Japan, its nimble spirit—a "bubbling cauldron of small firms, vigorous because of ferocious competition between them, formidable because they were capable of alliances and collaborations"—made it rich with creative ferment, especially when compared with the "self-contained, vertically integrated" cultures of its faraway competitors.

Three decades later, public policy was still shaping Silicon Valley. "While Wall Street recovered painfully from the crisis of 2008, its wings clipped by regulators aiming to forestall a repeat taxpayer bailout," Mallaby writes, "the West Coast variety of finance expanded energetically along three axes: into new industries, into new geographies, and along the life cycle of startups." Many politicians today threaten trustbusting crusades against Google and Amazon, or rumble about changing which types of speech are allowed on Facebook and YouTube. What legislators and regulators do now could shape V.C. appetites for years to come, altering which types of investments firms make or how many new entrants can emerge in the face of greater regulatory costs.

One of the book's strongest throughlines is that there's no one correct way to evaluate a company's promise or to foster its growth. On Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley, there are activist V.C.s such as the late Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital, who would aggressively intervene in the decisions made by leaders at his portfolio companies, and there are passive V.C.s like Peter Thiel, who have deliberately chosen to be more deferential to founders. There have also been safety-net V.C.s whose presence has allowed outside management to take the risk of coming aboard young ventures, knowing their V.C. network would help them land on their feet if all hell broke loose.

That's what happened when Kleiner Perkins' John Doerr wanted to bring in an outside founder as a condition of investing in a promising company called Google. Doerr convinced Eric Schmidt, who at the time was running a software company named Novell, that he should take a chance on the search company, signaling to Schmidt that Kleiner Perkins would help him land in a comparably good position if Google failed to take off. And so the right manager made the right jump at the right time.

V.C.s have served as bubble enablers, fecklessly pumping cash into startups that are poorly managed or that peddle flawed products. They have been envoys to Wall Street and establishers of credibility. And they have been crazy gamblers like billionaire Masayoshi Son, whom Mallaby accuses of "barely pausing to sort gems from rubbish."

Although outsiders may not see it, V.C.s have strong incentives to mediate competition. Silicon Valley, in Mallaby's telling, is a land of cooperative as well as competitive pressures. In the late '90s, Max Levchin pitched Thiel on an encryption technology he was working on, and Thiel applied the tech to cash payments. They called the payment processor PayPal and named the company Confinity, but they struggled to raise money from top Silicon Valley firms, instead getting funding from the Finnish company Nokia. Competitor X.com, helmed by Elon Musk, secured five times as much Sequoia funding as Confinity, although Confinity's technical talent was arguably better than X.com's. "Pretty soon," Mallaby writes, "both sides understood that they could fight to the death or end the bloodshed by merging."

Back in the '80s, Thomas Perkins "presided, Solomon-like, over the dispute between two Kleiner Perkins portfolio companies," Mallaby recalls. Sometimes the future echoes the past, even in the land where all things must be creatively destroyed: "Twenty years later [Sequoia's Michael] Moritz was determined that cooperation should prevail. Sequoia would be better off owning a small share of a grand-slam company than a large share of a failure." Moritz thus had a clear incentive to facilitate the birth of PayPal after rounds of heated negotiations (and a power struggle between Thiel and Musk). PayPal's ongoing dominance is evidence that Moritz's instinct was correct. And the universe of technology companies that have sprung from, or been funded by, people involved in the early days of PayPal—Tesla, YouTube, Palantir, LinkedIn—has shaped our world in ways good, bad, and unexpected.

Some of today's biggest tech critics have long been thorns in venture capitalists' sides, nursing grudges and filing suits long before they set their sights on dismantling Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (which protects free speech on the internet), breaking up tech companies, or attacking the idea of a Twitter run by Elon Musk. Investor Ellen Pao, who last April wrote in The Washington Post that "Musk's appointment to Twitter's board shows that we need regulation of social-media platforms to prevent rich people from controlling our channels of communication," unsuccessfully sued Kleiner Perkins for alleged gender discrimination back in May 2012. Pao said she was denied a promotion because of her gender; supervisors claimed it was because of her performance. She lost the lawsuit in court. Since then, she has spent eight months as CEO of the message board platform Reddit (a Y Combinator company) and, more recently, has been a tech critic and a promoter of diversity and inclusion initiatives.

Mallaby treats Pao and other early critics fairly, detailing some evidence of bad practices in Silicon Valley. There were sexual come-ons, he reports, and some women were cut off from male V.C. networks. But he doesn't think there's airtight evidence that women were systematically denied promotions. It is interesting to see the same names calling for new tech regulations in The Washington Post a decade later.

Mallaby also notes that some V.C.s, such as Kleiner Perkins' Doerr, made deliberate efforts to bring more women into the Sand Hill investment scene, believing that "exclusion of women represented wasted talent" and that such talent ought to be profitably captured. But Doerr failed to appropriately manage the integration of more women into the firm, which some female V.C.s claim hindered their longer-term success at Kleiner. There's a lesson there for those who call for governments to mandate corporate diversity quotas. In the V.C. world, blunt-force initiatives didn't create the lasting change that was desired; it was incrementalism that brought a better situation for women in tech, creating incentives that spurred investors like Doerr to address festering problems.

The Power Law is a useful, thorough corrective to tech critics who don't recognize the delicate balance that allowed the tech boom of the last half-century to happen. As V.C.-backed companies struggle with profitability and possible layoffs loom, and as we face a broader sense that the tech party may be over, it's more important than ever to understand the components that made this period of flourishing possible."

Friday, December 30, 2022

Climate Fact Check 2022 Report Debunks Mainstream Media’s Tall Tales

"Climate Fact Check 2022, a report issued this week by CEI and several other nonprofit groups, debunks claims made in the mainstream media this year about the disastrous impacts of climate change. Major weather events blamed on climate change by the Associated Press, New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, BBC, and other outlets include: floods in Pakistan, Hurricane Ian, droughts in Europe and China, African famine, Yellowstone River floods, low water levels at Lake Mead, and lack of snow for World Cup skiing.

To take perhaps the most egregious example of climate hype in the past year: “In this World Cup season, climate change is winning,” blared a Washington Post headline in November. Shorter winters were blamed for it being cold enough to hold only one of eight races as of mid-November.

Here’s the Climate Fact Check:

First, winter doesn’t begin until December 21. Next, when World Cup skiing started in the 1960s, the season began in January. Now it begins in October, which is early-to mid-autumn. If the competition began in the winter everything would likely be okay because wintertime snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere has been increasing since the 1960s.

Seth Borenstein in an AP story summed up the estimated costs of damages due to climate change in 2022 at $268 billion. Climate Fact Check 2022 simply notes that:

The Associated Press, a long-time major newswire service, now accepts donations specifically to fund its climate coverage. In 2022, in fact, the Associated Press admitted to receiving $8 million in donations to cover

climate. The money came from very large foundations which have been pushing climate alarmism for decades, including the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Quadrivium, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation.As Steve Milloy, principal author of the report, told Fox News: “It’s hard to claim it’s news when you’re being paid to report only one side of the climate discourse.”

Climate Fact Check 2022 was produced by CEI, the Heartland Institute, the Energy and Environment Legal Institute, the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow, and the International Climate Science Coalition."

The Biden Administration has enacted policies that will add more than $4.8 trillion to budget deficits between 2021 and 2031

See 22 Top Fiscal Charts of 2022 from The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Excerpt:

"Since January 2021, the Biden Administration has enacted policies through legislation and executive actions that will add more than $4.8 trillion to budget deficits between 2021 and 2031. The $4.8 trillion is the net result of roughly $4.6 trillion of new spending, about $500 billion of tax cuts and tax breaks, and $700 billion of additional interest costs that are partially offset by $400 billion of spending cuts and $600 billion of revenue increases."

If economists cannot predict the macroeconomy, then governments cannot successfully intervene and manipulate

See Economists Can’t Forecast by Chris Edwards of Cato.

"Contrary to the confident‐sounding claims of experts in the media, economists cannot accurately predict the macroeconomy. Economists have an awful record at forecasting inflation, interest rates, gross domestic product, and other macro variables. Below I excerpt from a Wall Street Journal column summarizing the failed record of forecasting 2022’s inflation, interest rates, and stock market.

This is important for public policy because if economists cannot predict the macroeconomy, then governments cannot successfully intervene and manipulate. The administration thought that its $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan passed in March 2021 would aid the economy, but it proved to be hugely damaging by helping to spur high inflation.

Businesses and stock market investors often make mistakes, but they can change direction quickly as conditions change. The government, by contrast, is a rigid institution led by people who rarely admit mistakes. So when politicians move economic resources around, the resources usually get stuck in low‐value uses for years on end, as discussed in this study on government failure.

The Wall Street Journal reports that while economists projected corporate profits accurately this year, they were far off in projecting the stock market, inflation, and interest rates:

The average forecast last December for this month’s interest rate was just 0.5%, according to Consensus Economics. The Fed this month raised rates to a range of 4.25% to 4.5%. Miss a change of this importance and there is little hope of getting anything else right.

Few even called the direction of stocks correctly. JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup were all bullish, expecting the S&P 500 to hit 5100, 5050 and 4900 respectively. Bank of America‘s strategists were rightly bearish, for the right reason, predicting a rates shock. But their 4600 target was a drop of just 3% from when they published their prediction. The S&P 500 closed on Friday at 3844.82, down 19% for the year so far.

Underlying all these errors, and those from pretty much everyone else, was the mistaken belief that inflation would quickly go away. Covid‐related supply‐chain problems would fade away, they thought, and falling inflation would allow the Fed to raise rates gently, sparing asset prices. Instead, inflation spread to virtually all categories of goods and services, worsened by the energy‐ and food‐price spikes that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

If they cannot successfully manipulate the economy, then what should governments do? Economist Adam Smith advised them to adopt the “simple system of natural liberty.” By refraining from intervening:

the sovereign is completely discharged from a duty, in the attempting to perform which he must always be exposed to innumerable delusions, and for the proper performance of which no human wisdom or knowledge could ever be sufficient; the duty of superintending the industry of private people, and of directing it towards the employments most suitable to the interest of the society.

More on failed macro forecasting here, here, here, and here."

Thursday, December 29, 2022

Does reducing lead exposure limit crime?

"These results seem a bit underwhelming, and furthermore there seems to be publication bias, this is all from a recent meta-study on lead and crime. Here goes:

Does lead pollution increase crime? We perform the first meta-analysis of the effect of lead on crime by pooling 529 estimates from 24 studies. We find evidence of publication bias across a range of tests. This publication bias means that the effect of lead is overstated in the literature. We perform over 1 million meta-regression specifications, controlling for this bias, and conditioning on observable between-study heterogeneity. When we restrict our analysis to only high-quality studies that address endogeneity the estimated mean effect size is close to zero. When we use the full sample, the mean effect size is a partial correlation coefficient of 0.11, over ten times larger than the high-quality sample. We calculate a plausible elasticity range of 0.22-0.02 for the full sample and 0.03-0.00 for the high-quality sample. Back-ofenvelope calculations suggest that the fall in lead over recent decades is responsible for between 36%-0% of the fall in homicide in the US. Our results suggest lead does not explain the majority of the large fall in crime observed in some countries, and additional explanations are needed."

Jeffrey Rogers Hummel on Slavery

"Chattel slavery involves the ownership by one person of another. This entry focusses on the operation of that labor system in the United States. Although chattel slavery dates back to the dawn of civilization, in the area that became the United States it first emerged after the importation of Africans to the Virginia colony in 1619. Prior to the American Revolution, all British colonies in the New World legally or informally sanctioned the practice. Nearly every colony counted enslaved Africans among its population. Only during and after the Revolution did the northern states abolish the institution or begin to implement gradual emancipation. But slavery was more economically entrenched in the southern states and became more so over time. By the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, slaves constituted one-third of the total slave-state population of 12.3 million.

Slavery has captured the attention of economists since at least the eighteenth century. Two basic questions have remained intertwined throughout the history of economic thought regarding this ancient institution. First, was slavery profitable? And second, was slavery efficient? Was it profitable to individual slaveholders, in the sense of offering a reasonable prospect of monetary return (or some other material reward) comparable to what they could earn from other enterprises? Efficiency refers to overall economic gains. Did the exploitation of slave labor allocate and use resources in ways that fostered aggregate wealth and welfare, regardless of how unfairly it distributed wealth? Did it produce goods and services as abundant and valuable as alternative labor arrangements could have? Often economists and historians have reached identical answers to both questions, concluding that either slavery was both unprofitable and inefficient or both profitable and efficient.

These are the opening paragraphs of Jeffrey Rogers Hummel, “U.S. Slavery and Economic Thought,” in David R. Henderson, ed. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. It’s the latest addition to the on-line encyclopedia. It’s very long but well worth reading.

Another excerpt:

Strictly speaking, economists usually and most broadly employ the term “efficiency” as a measure of welfare rather than of output. Thus, while economic historians now agree that antebellum slavery marginally increased the output of cotton and other products, it still could have diminished total welfare. In measuring efficiency, economists have no precise unit to compare the subjective gains and losses from involuntary transfers. But because most coercive transfers in the Old South were from poor slaves to rich slaveholders, to assume unrealistically that such transfers were a wash in which slaveholder gains equaled slave losses is to bias the analysis in favor of slavery. Thus, if welfare losses still exceed gains, even with this bias present, one can be certain that slavery was inefficient. Hummel, in his dissertation, “Deadweight Loss and the American Civil War” (2001, updated 2012), integrated previous work into a systematic challenge to slavery’s efficiency.[9] He identified three sources of deadweight loss: output inefficiency, classical inefficiency, and enforcement inefficiency.

And an excerpt on the New History of Capitalism:

By the twenty-first century the slavery debates among economists had become quiescent. One major subsequent contribution is Olmstead and Rhode’s “Biological Innovation and Productivity Growth in the Antebellum Cotton Economy” (2008). They found that average daily cotton-picking rates quadrupled between 1801 and 1862, mainly due to new cotton varieties. But among historians, those describing their own work as part of a “New History of Capitalism” now claim that slavery was the primary source of overall U.S. economic growth in the antebellum period. Two of their major works are Beckert’s Empire of Cotton (2014) and Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told(2014). [15] While embracing the finding that slavery was productive, these historians otherwise largely ignore all previous work of economists. Yet the idea that slavery was essential for cotton production, which drove national growth, is belied by the fact that just five years after the Civil War’s end the physical amount of cotton produced was approaching its prewar peak, mainly because of increased acreage devoted to cotton cultivation, despite the fall in southern real income.

Baptist went so far as to ignore Olmstead and Rhode’s explanation for the increase in cotton-picking rates, attributing it instead to a whipping regime of calibrated torture, steadily increasing over sixty years. Horrendous as torture is, the claim that it could account for productivity continually increasing for more than half a century is implausible on its face. Ignorance of national income accounting and Baptist’s double counting led him to attribute almost half of U.S. economic activity in 1836 to cotton production. Although cotton was the largest U.S. export, it never exceeded 5 percent of GDP. Olmstead and Rhode (2018) offers a comprehensive and scathing critique of the New History of Capitalism’s works on slavery.[16]"

Wednesday, December 28, 2022

Canada’s health-care wait times hit record high of 27.4 weeks

By Mackenzie Moir & Bacchus Barua of The Fraser Institute.

"Although the worst of the pandemic is now in the rearview mirror, Canada’s health-care system continues to struggle with poor resource and staff availability, health-care worker burnout, and chronic hospital overcapacity. And Canadians now also face the longest wait times for elective surgery on record.

According to the Fraser Institute’s latest annual survey of physicians, patients could expect a median wait of 27.4 weeks between referral to a specialist by a general practitioner and receipt of treatment in 2022, the fourth consecutive year wait times have increased. This year’s median wait is almost three times longer than the 9.3-week wait recorded in the first national survey in 1993, and 6.7 weeks longer than deemed “reasonable” by physicians.

The survey covers all 10 provinces across 12 core medical specialties and measures waits for “elective” surgeries, which are scheduled (in contrast to emergency surgeries) but are still medically necessary. If patients wait too long for some elective procedures, they may experience deteriorating health, permanent disability and sometimes death.

Of course, wait times vary considerably depending on the province and specialty. Prince Edward Island reported the longest wait time this year (64.7 weeks) while Ontario reported the shortest (20.3 weeks). We also see significant variation between specialties. For example, patients across the country face the longest waits for neurosurgery (58.9 weeks) and plastic surgery (58.1 weeks) while wait times for radiation (3.9 weeks) and medical oncology (4.4 weeks) were the shortest.

To be clear, this isn’t a COVID problem. While the pandemic and associated surgical postponements may help partially explain why wait times have increased over the past three years, waits for elective surgeries were remarkably long before the first recorded case of COVID-19 in Canada—in 2019, Canadians faced a median wait of 20.9 weeks for elective care.

The pandemic has also affected the research environment, with the national survey response rate this year coming in at 7.1 per cent. Although 850 specialists still responded to the survey, this year’s response rate is lower than in years preceding the pandemic. That said, these findings align with data from decades of domestic research and international surveys that reveal Canada’s poor access to timely care. For example, in 2020 the Commonwealth Fund (CWF) found that Canada ranked at the bottom (11th of 11) for both timely specialist appointments (under four weeks) and elective surgeries (within four months). A similar study from the CWF found similar results in 2016, long before the pandemic.

Given these lackluster results and Canada’s continued and outsized reliance on the performance and generosity of our health-care workers, policy solutions are long overdue.

For years, the research has revealed familiar findings. Other countries with similar or lower spending on health care (as a share of their economies), which outperform Canada, employ markedly different approaches to universal health care. Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland all either partner with the private sector for the financing and delivery of universal care, or rely on the private sector as an pressure valve when the public system is overburdened. They tend to also incentivize the responsible use of resources by expecting patients to share the cost treatment (with exemptions for vulnerable populations), and fund hospitals based on activity (instead of Canada’s “global budgets”). Of course, these countries also faced their own challenges during COVID. But the difference is they entered the pandemic with more resources and shorter wait times and will, therefore, likely emerge in a better position, too.

If Canadians want to see their health-care system improve and wait times reduced, the provinces must consider bold reforms. It’s hard to imagine a more pressing policy issue in Canada today."

The lightship in economics

"Abstract

What role does government play in the provision of public goods? Economists have used the lighthouse as an empirical example to illustrate the extent to which the private provision of public goods is possible. This inquiry, however, has neglected the private provision of lightships. We investigate the private operation of the world’s first modern lightship, established in 1731 on the banks of the Thames estuary going in and out of London. First, we show that the Nore lightship was able to operate profitably and without government enforcement in the collection of payments for lighting services. Second, we show how private efforts to build lightships were crowded out by Trinity House, the public authority responsible for establishing and maintaining lighthouses in England and Wales. By including lightships into the broader lighthouse market, we argue that the provision of lighting services exemplifies not a market failure, but a government failure."

"Historically, maritime safety was provided through a plethora of different services meant to reduce the likelihood of being ship- wrecked (or beached). This included services like ballastage (filling the bottom of an empty ship with sand to give it stability) or pilotage (local experts boarding at safe points to guide foreign ships to ports). These services were purely private goods – they were excludable and rivalrous. They were also complements to light- houses. For example, a pilot’s efficiency would be superior if he had access to a lighthouse. This opens the door the possibility for firms to bundle the production of private goods and public goods in ways that can price in free-riders (Bakos and Brynjolfsson, 1999). As Cornes and Sandler (1984, 1986) pointed out, once joint produc- tion of private and public goods is possible, most of the conditions behind the conventional wisdom regarding the provision of pure public goods no longer hold. More importantly, the complementar- ity between the goods brings out a capacity to privatize the whole bundle even if one of its components is a public good. The comple- ments to the lighthouse have never, to the best of our knowledge, been considered in the economics literature.""Candela and Geloso (2018a) illustrate this point with respect to lightships, also known as floating lighthouses. In 1731, two entrepreneurs, David Avery and Robert Hamblin, moored the world’s first modern lightship in the Thames River. The particular importance of the Nore lightship was that it was introduced pre- cisely at a time when traffic at the Port of London was increasing rapidly. During the 18th century merchant traffic entering the Port of London stood increased nearly fourfold, from 157,035 tons in 1702 to 620, 845 tons by 1794 (House of Commons, 1796, p. V). The production of the lightship was strategically placed at the shallow mouth of the Nore bank, at the confluence of the Thames and Med- way rivers, where lighthouses could not be constructed and the risk of shipwreck was highest. The willingness of entrepreneurs, such Avery and Hamblin, to supply a lightship, rather than construct- ing another navigational aid, such as buoy or beacon, emerged only when the profitability of accommodating additional commercial ships rose. Therefore, the consumption of lighting services grew more rivalrous as commerce increased, as well the cost of ship- wreck. It was the rivalrousness of lighting services that incentivized Avery and Hamblin to advertise their product, price discriminate based on tonnage, and therefore craft ingenious way to exclude non-payers. This included the use of subscription payments by which they were able to overcome free-riding. The fact that the lighthouse (and lightship) has been treated as a public good, and therefore as non-rivalrous, has directed economists’ attention away from the various ways in which lighting services were provided, and how excludability was an endogenous feature of such rival- rousness"

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Not So “Green” Technology: The Complicated Legacy of Rare Earth Mining

From The Harvard International Review. Excerpt:

"Most people view technology as the future, a force of good that will generally improve quality of life around the world. In the business sector, Silicon Valley and tech startups exhibit massive growth potential; in manufacturing, new machinery and automation are boosting efficiency; and in the environmental realm, green technology presents the best prospects for decarbonization.

But as much as technology is hailed as the panacea of the future, most of these innovations have a dirty underside: production of these new technologies requires companies to dig up what are referred to as rare earth elements (REEs).

REEs describe the 15 lanthanides on the periodic table (La-Lu), plus Scandium (Sc) and Yttrium (Y). Contrary to what the name suggests, REEs are abundant in the earth’s crust. The catch is that they come in low concentrations in minerals, and even when found, they are hard to separate from other elements, which is what makes them “rare.” Perhaps these elements also get their name from being rarely discussed, even though everything from the iPhone to the Tesla electric engine to LED lights use REEs. Demand for these elements is projected to spike in coming years as governments, organizations, and individuals increasingly invest in clean energy. An electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, and a wind plant requires nine times more minerals than a gas-fired plant. With current estimates, demand for REEs could increase six-fold by 2040. Lithium and cobalt demand could increase ten to twenty times by 2050 because of electric cars. Demand for dysprosium and neodymium is estimated to increase seven to twenty-six times over the next 25 years as a result of electric vehicles and wind turbines. But REEs also have grim prospects: the way companies extract REEs largely damages communities and contaminates surrounding areas.

Mining Externalities

There are two primary methods for REE mining, both of which release toxic chemicals into the environment. The first involves removing topsoil and creating a leaching pond where chemicals are added to the extracted earth to separate metals. This form of chemical erosion is common since the chemicals dissolve the rare earth, allowing it to be concentrated and then refined. However, leaching ponds, full of toxic chemicals, may leak into groundwater when not properly secured and can sometimes affect entire waterways.

The second method involves drilling holes into the ground using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes and rubber hoses to pump chemicals into the earth, which also creates a leaching pond with similar problems. Additionally, PVC pipes are sometimes left in areas that are never cleaned up.

Both methods produce mountains of toxic waste, with high risk of environmental and health hazards. For every ton of rare earth produced, the mining process yields 13kg of dust, 9,600-12,000 cubic meters of waste gas, 75 cubic meters of wastewater, and one ton of radioactive residue. This stems from the fact that rare earth element ores have metals that, when mixed with leaching pond chemicals, contaminate air, water, and soil. Most worrying is that rare earth ores are often laced with radioactive thorium and uranium, which result in especially detrimental health effects. Overall, for every ton of rare earth, 2,000 tons of toxic waste are produced.

China currently dominates the REE market, accounting for 85 percent of the global supply in 2016. Australia is the next largest producer contributing 10 percent of the market, yet barely making a dent in China’s monopoly. For comparison, in 2018 China produced 120,000 tons of REEs while the United States produced 15,000 tons. China has even used REEs as a tool to coerce other nations: in 2010, it blocked REE exports to Japan as punishment for Japan’s detention of a Chinese captain. More recently, it considered limiting REE exports to the United States in response to tariffs put in place by former US President Donald Trump, presenting a tremendous threat since the US defense industry relies heavily on these minerals. However, only 35 percent of the world’s REE reserves are in China, raising questions about how the country has been able to monopolize the industry.

China’s REE Empire

China was only able to establish such dominance over the REE industry in large part because of lax environmental regulations. Low cost, high pollution methods enabled China to outpace competitors and create a strong foothold in the international REE market. This market is now booming: China spiked its outputs for the first half of 2021 by more than 27 percent, hitting record levels of REE extraction as demand increases.

The most infamous mine in China is Bayan-Obo, the largest REE mine in the world. Even more infamous than the mine itself is the tailing pond it has produced: there are over 70,000 tons of radioactive thorium stored in the area. This has become a larger issue recently because the tailing pond lacks proper lining. As a result, its contents have been seeping into groundwater and will eventually hit the Yellow River, a key source of drinking water. Currently, the sludge is moving at a pace of 20-30 meters per year, a dangerously rapid rate.

There are plenty more examples of unsafe mines throughout China. The village of Lingbeizhen in the Southern Jiangxi province has leaching ponds and wastewater pools exposed to open air. It is easy to imagine toxic chemicals spilling into groundwater or waterways since they are left unmonitored and vulnerable to the whims of nature. In another mine, so much wastewater was created that China had to build a treatment facility to clean 40,000 tons of wastewater per day before letting the water flow back into the river.

Workers are also suffering from health complications due to exposure to these toxic chemicals. Worker safety is not prioritized or monitored in these mines, resulting in skin irritation and disruptions to their respiratory, nervous, and cardiovascular systems. Human rights abuses have been reported throughout mines in these areas as laborers are overworked and underpaid.

China has taken some steps to address issues arising from REE mining, but not nearly enough. China estimates US$5.5 billion in damage from illegal mining that needs to be cleaned. The Chinese government has also acknowledged the existence of so-called “cancer villages” where a disproportionately large number of people have fallen ill with cancer due to mining-based pollution. Officials have shut down some smaller illegal mining operations, looking to consolidate mining under six state-owned groups that the Chinese government claims will maintain better practices surrounding toxic waste management, but farmers claim state-owned companies are just as bad. Some argue state-owned companies are worse because they poison communities with governmental support. For example, in Zhongshan, a company claimed it was extracting resources before the government built a highway in the area, but after the highway was finished, it refused to leave. People in the area began noticing wastewater seeping into their farms, and they were forced to inhale sulfur every time they went outside. 15 protestors were arrested in 2015, and ten more protestors were arrested two years later. Some farmers from Yulin, an area with REE mining, have a similar story: they started protesting when they saw their crops and livelihoods being affected by REE extraction. Ten protesters from Yulin were detained in May 2018, and seven still remain in detention.

For all its narratives of progressive reform on REE mining, China understands the value of its monopoly and wants to maintain the status quo. It appears as though China is now moving its operations to Africa, where it can contaminate outside communities instead of exposing its citizens at home to the risks of REE mining. Though some of these operations are conducted by private companies, the six major mining companies are all state-owned enterprises. China has achieved exclusive rights to the REE deposits in a handful of African countries in return for infrastructure building. For example, China obtained the rights to lithium mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in return for building national roads, highways, and hospitals. Similarly, China obtained commercial licenses for REE mines in Kenya by agreeing to build a US$666 million data center. More deals are surfacing in Cameroon, Angola, Tanzania, and elsewhere. Though African nations accept these deals now, some worry that this is a long-term strategy for China to lock African nations into a cycle of debt. In order to counter Chinese influence, the United States has restarted some of its older REE mining operations in various states. The government wants to ensure that critical US industries can remain separate from China in the event of a larger dispute. Thankfully, the US has more stringent environmental regulations on its REE mining, though its methods are certainly not perfect."

The faux urgency of the climate crisis is giving us no time or space to build a secure energy future

"There is a growing realisation that emissions and temperature targets are now detached from the issues of human well-being and the development of our 21st century world.

JC note: this is the text of my op-ed for SkyNews that was published several weeks ago

For the past two centuries, fossil fuels have fueled humanity’s progress, improving standards of living and increasing the life span for billions of people. In the 21st century, a rapid transition away from fossil fuels has become an international imperative for climate change mitigation, under the auspices of the UN Paris Agreement. As a result, the 21st century energy transition is dominated by stringent targets to rapidly eliminate carbon dioxide emissions. However, the recent COP27 meeting in Egypt highlighted that very few of the world’s countries are on track to meet their emissions reductions commitment.

The desire for cleaner, more abundant, more reliable and less expensive sources of energy is universal. However, the goal of rapidly eliminating fossil fuels is at odds with the urgency of providing grid electricity to developing countries. Rapid deployment of wind and solar power has invariably increased electricity costs and reduced reliability, particularly with increasing penetration into the grid. Allegations of human rights abuses in China’s Xinjiang region, where global solar voltaic supplies are concentrated, are generating political conflicts that threaten the solar power industry. Global supply chains of materials needed to produce solar and wind energy plus battery storage are spawning new regional conflicts, logistical problems, supply shortages and rising costs. The large amount of land use required for wind and solar farms plus transmission lines is causing local land use conflicts in many regions.

Given the apocalyptic rhetoric surrounding climate change, does the alleged urgency of reducing carbon dioxide emissions somehow trump these other considerations? Well, the climate ‘crisis’ isn’t what it used to be. The COP27 has dropped the most extreme emissions scenario from consideration, which was the source of the most alarming predictions. Only a few years ago, an emissions trajectory that produced 2 to 3 oC warming was regarded as climate policy success. As limiting warming to 2 oC seems to be in reach, the goal posts were moved to limit the warming target to 1.5 oC. These warming targets are referenced to a baseline at the end of the 19th century; the Earth’s climate has already warmed by 1.1 oC. In context of this relatively modest warming, climate ‘crisis’ rhetoric is now linked to extreme weather events.

Attributing extreme weather and climate events to global warming can motivate a country to attempt to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels. However, we should not delude ourselves into thinking that eliminating emissions would have a noticeable impact on weather and climate extremes in the 21st century. It is very difficult to untangle the roles of natural weather and climate variability and land use from the slow creep of global warming. Looking back into the past, including paleoclimatic data, there has been more extreme weather everywhere on the planet. Thinking that we can minimize severe weather through using atmospheric carbon dioxide as a control knob is a fairy tale. In particular, Australia is responsible for slightly more than 1% of global carbon emissions. Hence, Australia’s emissions have a minimal impact on global warming as well as on Australia’s own climate.

There is growing realization that these emissions and temperature targets have become detached from the issues of human well-being and development. Yes, we need to reduce CO2 emissions over the course of the 21st century. However once we relax the faux urgency for eliminating CO2 emissions and the stringent time tables, we have time and space to envision new energy systems that can meet the diverse, growing needs of the 21st century. This includes sufficient energy to help reduce our vulnerability to surprises from extreme weather and climate events."

Monday, December 26, 2022

The Little Red Schoolhouse Could Do With a Little Competition

Choice hurts rural schools: The teachers unions promote another easily debunked myth

By Corey DeAngelis. Excerpts:

"Teachers unions and their allies are arguing that giving families choices in education would devastate their state’s rural public schools."

"These same politicians also claim that rural constituents wouldn’t benefit from school choice because the local public school is their only option. These arguments can’t both be true. If rural families didn’t have any other options, public schools wouldn’t suffer. And if rural public schools are as great as the teachers unions say they are, they would have no need to worry about a little competition."

"As Florida has increased its scholarship programs over the past two decades, the number of private schools in the state’s rural areas has increased from 69 in 2002 to 120 in 2022. Although more than 70% of Florida students are eligible for private-school scholarships, the share of students in Florida’s rural private schools has grown by only 2.4 percentage points since 2012.

Despite a growth in private options, the mass exodus from rural public schools that many have warned about hasn’t happened. In fact, 25 of the 28 studies on the topic find that private-school choice leads to better outcomes in public schools, from increased test scores to reduced absenteeism and suspensions. Competition is a rising tide that lifts all boats."

"“Harm” inflicted on rural schools is no longer a legitimate excuse to oppose school choice. The claim certainly hasn’t prevented others from enacting innovative education initiatives. The nine most rural states, according to Census Bureau data, all have some form of private school choice. West Virginia has the second-most-expansive education-savings-account program in the nation, behind Arizona. Maine and Vermont are home to the oldest private-school voucher programs in the country—both passed in the 19th century—which were specifically designed for students in rural areas without public schools."

"giving families more options doesn’t result in a net loss of jobs; school choice simply allows families to determine where those jobs are concentrated.

According to OpenSecrets, over 90% of campaign contributions from public-school employees in deep-red rural Texas went to Democrats during the last election cycle. As education researchers Jay P. Greene and Ian Kingsbury noted, school choice merely shifts “some of the jobs from public schools dominated by Democrats to other schools whose values would be more likely to align with the those of the parents in those areas.”"

The Inflation Pain You Don’t See

Definitions of ‘middle class’ miss one vital factor that shows how much price hikes hurt Americans

By George Zuo. He is an applied microeconomist at the RAND Corp. Excerpts:

"Far more American households earn a middle-class income than enjoy a middle-class lifestyle. In a recent RAND study I co-authored, we defined middle-class households as those who spent 40% to 90% of their after-tax income on necessities: housing, food, clothing, transportation, education, child care, healthcare and personal-care products such as shampoo and toothpaste. We found that one-third of middle-income earners—and a disproportionate share of those who are young, black, Hispanic and single-parent households—couldn’t live a middle-class lifestyle.

Inflation makes the problem worse. In a separate analysis, my colleagues and I applied our study’s definition to consumption profiles from September 2021 as a pre-inflation benchmark and one-year inflation rates separately for food, education, healthcare, housing, personal care, transportation, apparel and child care.

We found that the middle class grew last year, but for all the wrong reasons. If middle-class households didn’t cut back on any of those things—or get better-paying jobs—roughly 7.5% fell into the working class under our model. But 12.7% of the upper class fell into the middle class. Single parents, renters, younger adults, those without college degrees, and black and Hispanic households were all more likely to have been pushed out of the middle class by inflation.

Because of how inflation rates differ across goods and services, the lower the household’s income, the harder inflation hit. For middle-class households, the percentage of after-tax income spent on necessities jumped from 60% to 65%. For upper-class households, the shift was from 26% to 28%. Working-class households already needed 108% of their monthly income to cover the basics in 2021; in 2022 it was 118%. They are either dipping into savings, getting help from relatives or safety-net programs, or going into debt."

Friday, December 23, 2022

Did the Death of “Net Neutrality” Live Up to Doomsday Predictions?

By Peter Jacobsen. Peter Jacobsen teaches economics and holds the position of Gwartney Professor of Economics. He received his graduate education at George Mason University.

"This week for Ask an Economist I’m answering a question sent to me by Lawrence. He asked, “what [has] been the effect of getting rid of net neutrality?”

To answer this question, we have to wind back the clock to 2017. Then-chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Ajit Pai successfully led an effort to repeal a set of 2015 regulations on Internet Service Provider (ISP) companies originally put into place by the Obama Administration.

The simplest summary of net neutrality regulations is that they required ISPs to enable access to content on the internet at equal speeds and for equal costs. For example, your ISP charging you to get faster speeds on YouTube or blocking High Definition access on Netflix would be examples of violations of net neutrality.

The idea of paying your ISP extra to have access to certain websites is a scary one, but it appears the worst fears associated with the end of net neutrality were overstated. To some extent proponents of net neutrality are the victim of their own apocalyptic marketing.

The Rumors of the Internet’s Death Were Greatly Exaggerated

If you spent any time on the internet during the death of net neutrality, it was hard to miss it. On July 12, 2017 websites across the internet coordinated their messages for the “battle for the net.”

Websites including Amazon, Netflix, YouTube, and Reddit called their users to fight for “a free and open internet.”

On Twitter, #SaveTheInternet thrived, seemingly implying the internet itself was facing an existential threat.

After the decision by the FCC, CNN briefly declared it was “the end of the internet as we know it.”

Unfortunately for all kinds of doomsday prophets, extreme rhetoric always looks silly in hindsight when it fails to pan out.

Obviously we aren’t seeing ISPs charge users different amounts to use different websites in any systematic way. There’s no “pay your ISP to access Hulu” package yet. So already it’s clear some of the doom and gloom was over-hyped.

Fears of ISPs offering “fast lanes” to make users pay more for better service don’t seem to have materialized either. The only example of this sort of thing I could find was a Cox Communications trial of an “Elite Gamer” service. But this service was unlike the “fast lanes” hyped up by net neutrality proponents in that it never offered a less throttled experience and would have been permissible under the old net neutrality rules.

One of the biggest concerns about the repeal of these regulations was that it would lead ISPs to favor their own services. For example, AT&T owns Time Warner and HBO Max. In theory, AT&T could silently throttle speed to competing streaming platforms like YouTube and Netflix, thereby destroying competition.

So did this happen? Well it’s hard to say. ISPs don’t exactly release an annual report of internet traffic they throttle. But we’re not totally in the dark, either.

Researchers at Northeastern University developed a method to monitor throttling known as Wehe. The researchers tested data throttling before and after net neutrality, and the results are surprising.

If the researchers are right, ISPs do throttle services, but they were already doing so before the repeal of net neutrality rules. In other words, the repeal of net neutrality had little to no impact on throttling. You can check out the data yourself.

Net neutrality advocates may see this as a win because it provides evidence that ISPs engage in this process. But it seems to me this hurts the case for these regulations more than anything. Why?

The data, if correct, show that the internet net neutrality advocates fought for when they were campaigning to keep net neutrality was no different than the internet without those regulations. The internet that advocates were fighting to save already had throttling!

To me this is akin to someone who believes they’re drinking a Coke and they’re complaining about it being worse than Pepsi, only to be told they are actually drinking a Pepsi.

Another problem the data present is that most of the throttled data rates are fast enough to stream standard definition videos on YouTube, for example. Some rates are even fast enough to stream high definition.

Granted, different streaming services require different data rates, and some users have a strong preference for HD, but I personally have a hard time getting worried about being “throttled” into having my YouTube videos look like they did while I was growing up. Admittedly, I’ve never been obsessed with “graphics,” but 480p has always looked fine to me.

So, has the repeal of net neutrality been totally without downsides? Some groups claim there have been negative effects. For example, one report lists as downsides:

- ISPs are throttling data according to Northeastern University

- The $15 Gamer Fast Lane

- Real-time locations of consumers can be sold by cell phone companies

- Frontier Communications is charging mandatory equipment rental fees—including to customers who don’t rent equipment.

Points one and two have already been addressed. The Northeastern University Report shows the throttling existed before the repeal of net neutrality, and the gamer fast lane (which as far as I can tell, no longer exists) was also in compliance with net neutrality rules.

Point three may be concerning to some, but doesn’t clearly seem to follow from the net neutrality repeal. It’s not clear the government couldn’t address that issue separately.

And the Frontier Communications case was also already addressed legally without use of net neutrality laws.

Admittedly, there could be preferential throttling happening at increased rates that we don’t know about and perhaps other issues, but the verdict from what I can tell is that concerns about the repeal of net neutrality were enormously overblown.

Meanwhile, the EU, which does support net neutrality regulations, seems to have performed worse than the US during the pandemic. European regulators outright asked streaming services to throttle video speeds.

What is the Economic Reason for Throttling?

It appears the downsides from ending net neutrality regulations have been minimal, but is it true that ISPs have an incentive to throttle data? And is it bad if they do?

Proponents of net neutrality often argue against an ISP’s ability to do so because providing 5mbps speed on Netflix costs the same as providing 5mbps of speed on YouTube, for example.

But that isn’t exactly right. It’s true that technologically providing the same speed to different platforms is the same, but economically it is different.

To understand why, consider the market for groceries. Imagine Dan, Patrick, and Jon are the only three customers in the market for oranges. Patrick is willing to pay at most two dollars for an orange, Dan is willing to pay at most three dollars, and Jon is willing to pay one dollar. Let’s say the cost of producing an orange is 50 cents.

How much should the grocery store charge for oranges? Well, if it charges three dollars it will sell only one orange to Dan for three dollars in revenue and 50 cents in cost. Total profit is $2.50.

What if the store lowers the price to two dollars? Well, Dan still buys an orange and this time he pays two dollars. At the lower price, Patrick is willing to buy an orange for two dollars. The store generates four dollars in revenue and it costs them one dollar (50 cents per orange sold). This means the store has earned three dollars in profit, which is more than it got for selling the orange for a higher price.

Now what if the store lowers the price to one dollar? Jon, Dan, and Patrick all buy an orange for 1 dollar each which leads to three dollars in total revenue. Each of the three oranges cost 50 cents, for a total cost of $1.50. This time the store only makes $1.50 in profit. This is less profit than the two dollar option, so the store won’t be lowering the price to one dollar. Two dollars is the profit-maximizing price for the store. (These figures are summarized in the table below.)

Price

Oranges Purchased (Dan)

Oranges Purchased (Patrick)

Oranges Purchased (Jon)

Total Oranges Purchased

Total Revenue

Total Cost

Profit

$3

1

0

0

1

1x$3=$3

$0.50

$2.50

$2

1

1

0

2

2x$2=$4

$1

$3

$1

1

1

1

3

3x$1=$3

$1.50

$1.50

Table 1: Grocery Store Profit With a Uniform Price for Oranges

So far in our example, we’ve assumed that stores only charge one price for oranges. That assumption isn’t a bad one. In many markets, there is a single stated price for all customers at some point in time. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Imagine the grocery store could charge different prices to different customers for oranges. Now the store could charge Dan three dollars, Patrick two dollars, and Jon one dollar. In this case the store would make six dollars in revenue (3+2+1) and have a cost of $1.50 (0.50+0.50+0.50) for a total profit of $4.50. This is the best result for the store so far!

Economists refer to this practice of charging customers different prices based on their willingness to pay price discrimination. And price discrimination exists all over the place.

Senior discounts, first-class plane seats, algorithmic pricing, and grocery store coupons are all methods through which companies try to assess and charge customers based on their willingness to pay.

Is this a “bad” thing? Well, economics as a value-free field can’t answer that question, but it can give us some insight which helps us make our decision.

The first question we should ask is, “who most benefits from price discrimination?” There are two groups who directly benefit. Consider our grocery store example. Store owners are able to make more profit when they successfully price discriminate. This is one beneficiary. The other beneficiary is customers with low willingness to pay.

If the grocery store weren’t allowed to charge different prices to different customers, we saw that the profit-maximizing price was two dollars. Jon isn’t willing to pay two dollars, so he doesn’t buy an orange. In the world of price discrimination, though, the store is able to profitably sell Jon an orange for $1. Jon benefits from this, otherwise he wouldn’t have been willing to make the trade at all! The store will try to get Jon to pay as much as he’s willing to, but it will never charge him such a high price that he doesn’t consider himself better off for the purchase.

If there is a “loser” due to price discrimination here, it’s Dan. Without price discrimination, Dan would buy an orange for two dollars. With it, the store is able to charge him three dollars.

It’s important to highlight that Dan isn’t actually worse off for buying the orange here. He is still willing to pay three dollars for an orange, so by definition he values the orange at more than three dollars. The trade is still a win-win, but Dan would certainly prefer to have been charged two dollars, other things held constant.

So what can this teach us about data throttling? Throttling involves charging relatively higher rates for different services (either by increasing the price or decreasing the quality). In other words, throttling is a form of price discrimination. And, much like the oranges, providing speed to customers for different streaming or gaming services doesn’t mean the ISP pays more to provide it.

The oranges in our example above always cost the store 50 cents to produce. But charging different customers different prices allowed the store to make more profit, so there is an implicit cost to charging a single price (in the form of losing higher profits).

ISPs, like grocery stores, are able to earn more profits by charging different rates for different speeds on websites. This is no different than grocery stores benefiting from mailing out coupons to charge different prices for the same product, or airlines benefiting from selling first-class tickets to customers who want to pay for luxury.

Those less willing to pay for internet are more likely to be able to afford it when ISPs price discriminate. So much like Jon benefitted from price discrimination, some consumers would here as well.

As far as groups who would prefer no price discrimination go, it’s possible heavy internet users who spend a lot of time streaming and gaming online would pay more if ISPs could price discriminate.

But, at least for now, it seems like the benefit to ISPs of price discrimination is fairly low, as evidenced by the minimal impact of ending net neutrality."

The Tradeoff Between Government Dependency and Self-Sufficiency

"When writing about employment and jobs, I often try to remind people about a handful of important observations.

1. A nation’s economic output is determined in part by the number of people gainfully employed.

2. The share of working-age people with jobs may be more important than the unemployment rate.

3. Worker compensation is determined by productivity and productivity is driven by investment.

4. Government redistribution programs can make joblessness more attractive than employment.

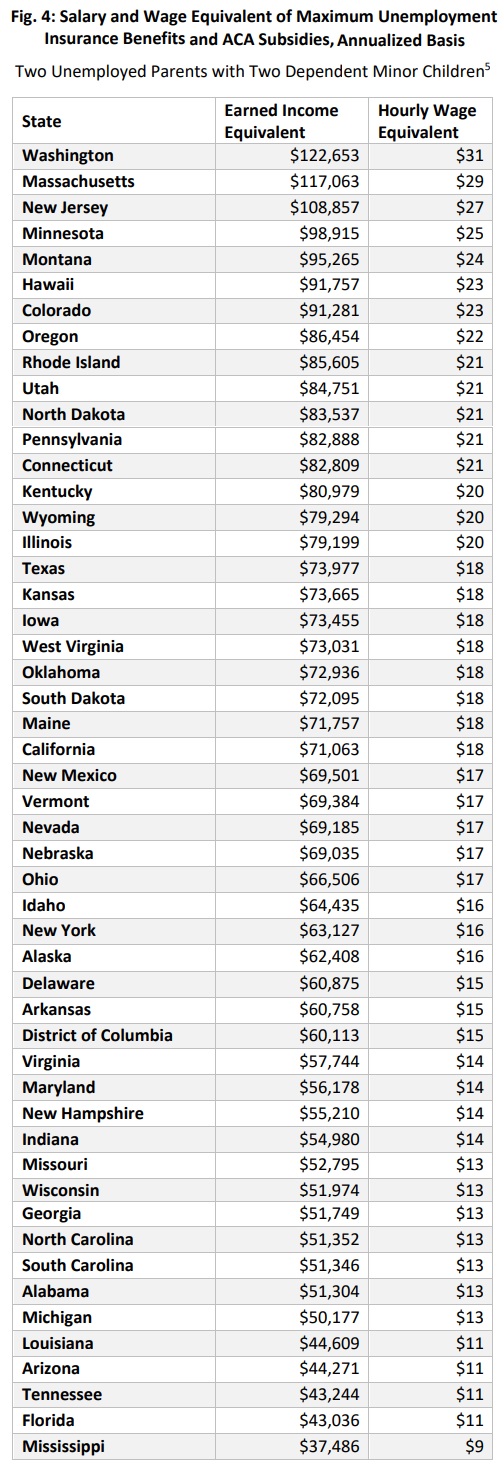

Regarding the final point, a new report from the Committee to Unleash Prosperity contains some very depressing data. Authored by Prof. Casey Mulligan of the University of Chicago and E.J. Antoni or the Heritage Foundation, it shows how Americans can be lured into unemployment.

"…with existing unemployment benefits and the dramatic recent expansion of ObamaCare subsidies, a spouse would have to earn more than $80,000 a year from a 40 hour a week job to have the same after-tax income as certain families with two unemployed spouses receiving government benefits. In these states, working 40 hours a week and earning $20 an hour would mean a slight reduction in income compared to two parents receiving unemployment benefits and health care subsidies. …In 24 states, unemployment benefits and ACA subsidies for a family of four with both parents not working are the annualized equivalent of at least the national median household income. …In more than half the states, unemployment benefits and ACA subsidies exceed the value of the salary and benefits of the average firefighter, truck driver, machinist, or retail associate in those states."For American readers, here’s a look at how some states make it very attractive to rely on government.

The good news (if we’re grading on a curve) is that some of the numbers are not as bad as they were during the pandemic, when politicians decided to provide super-charged unemployment benefits.

On the other hand, Obamacare subsidies are becoming an ever-bigger drag on the job market.

The big takeaway is that the numbers above reflect the impact of just two social insurance programs. The numbers would look worse if various means-tested programs were included.

For those interested in that data, here are state estimates from back in 2013, before Obamacare was fully in effect.

And for those who like international comparisons, here’s a look at the nations with the biggest handouts.

P.S. If Biden’s proposal for per-child handouts is approved, it would become far easier for people to leave the labor force and rely on handouts."

Striking the Right Balance on PFOA: Forever Chemicals

By Michael Dourson He has a PhD in toxicology from the University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine.

"The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is in the process of making a remarkable decision and one that will have repercussions throughout the US. Its proposed safe levels in water for the “forever” chemicals perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and its sulfonic acid (PFOS) are at extraordinary odds with other national authorities.

These chemicals resemble fatty acids that we would normally be able to eat. But since they are fluorinated, they are resistant to water and are long-lasting (we cannot digest them). As a result, they are very useful for many daily applications, like wrapping food to keep it from spoiling.

The EPA’s values are so much lower than others, 0.004 ppt (part per trillion –one sugar granule in 1 liter of water is 50,000 ppt), that small towns and cities throughout the US whose fire stations occasionally use fire-fighting foam containing such chemicals may be in jeopardy of lawsuits. Perhaps the EPA should reconsider since the World Health Organization (WHO) has dramatically different findings on PFOA and PFOS.

WHO reviewed much of the same data as EPA but concluded that the scientific uncertainties were too large to estimate the safe level for PFOA or PFOS confidently. Instead, the WHO made a risk management judgment that a level in water of 100 parts per trillion for PFOA and 500 parts per trillion for all related chemistries would be appropriate. WHO’s judgment is slightly above EPA’s current water value of 70 ppt. However, as noted above, this is projected to go much lower and slightly below the Australian value of 560 ppt. It would be hard to argue with the WHO that underlying scientific uncertainties preclude a definitive safe dose with such disparate values between these two government agencies.

Are the WHO’s PFAS limits for drinking water ‘weak’?

That is an argument made by a group of over 100 scientists and reported on by the Guardian. Perhaps some additional facts will help us understand this brouhaha better.

- The first fact, and one which the Guardian neglected or did not have room to mention, is that not only are “safe” water levels for PFOA and PFOS all over the map internationally (literally) but the EPA’s basis for its draft value, a single human observational study on a dubious effect, has again been rejected by the Food Standards of Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ, 2021).

- A second fact is that the letter was signed by over 100 individuals, with the preponderance being from academia. I do not doubt these scientists have done some outstanding bench work on PFAS chemistries, but with rare exceptions, academics are not known to be experts in determining the safe water levels of various chemistries. In fact, on this list of signatories, I only know one with excellent risk assessment skills. Of course, there may be others.

- A third fact, and one of which the Guardian author may have been unaware, was that two folks cited in his report are known to be expert witnesses for the plaintiff's bar, which was not acknowledged in the letter to the WHO nor the article. Acknowledgments such as this are a routine part of science work in this era, and missing them seems odd.

Permit me a personal note. I, too, was quoted in the article, but not all of my responses were mentioned. I had the pleasure of working at EPA twice; I also spent some time as an academic and founded and still work at the non-profit, tax-exempt organization, Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment (TERA). The work of this non-profit is approximately a third on behalf of industry and two-thirds for government regulators. Our group has four recent publications on PFOA, all unfunded. One received a paper-of-the-year award from the Society of Toxicology, and two were written with an international team of scientists. We have also initiated a new international collaboration on developing a safe dose range for PFOA and PFOS."

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Congress Has a Fiscal Road Map -- It Just Needs to Use It

By Veronique de Rugy. Excerpt:

"All told, it's possible to achieve deficit reduction of $7.7 trillion over 10 years. That's enough to accomplish what some people mistakenly believe to be out of reach: balancing the budget without raising taxes. There are also a few options to simplify the tax code by removing or reducing unfair individual tax deductions and by cutting corporate welfare.

For instance, it's high time for Congress to end tax deductions for employer-paid health insurance. This tax deduction is one of the biggest of what we wrongly call "tax expenditures." It's responsible for many of the gargantuan distortions in the health-care market and the resulting enormous rise in health-care costs. The CBO report doesn't eliminate this deduction; instead, it limits the income and payroll tax exclusion to the 50th percentile of premiums (i.e. annual contributions exceeding $8,900 for individual coverage and $21,600 a year for family coverage). The savings from this reform alone would reduce the deficit by roughly $900 billion.

A second good option is to cap the federal contribution to state-administered Medicaid programs. That federal block grant encourages states to expand the program's benefits and eligibility standards — unreasonably in some cases — since they don't have to shoulder the full bill. CBO estimates that this reform would save $871 billion.

CBO also projects that Uncle Sam could reduce the budget deficit by $121 billion by raising the federal retirement age. CBO's option would up this age "from 67 by two months per birth year for workers born between 1962 and 1978. As a result, for all workers born in 1978 or later, the FRA would be 70." Considering that seniors today live much longer than in the past and can work for many more years, this reform is a low-hanging fruit.

Congress could save another $184 billion by reducing Social Security benefits for high-income earners. I support a move away from an age-based program altogether since seniors are overrepresented in the top income quintile. Social Security should be transformed into a need-based program (akin to welfare). Nevertheless, the CBO's option would be a step in the right direction.

There are so many more options for long-term deficit reduction. All Congress needs is a backbone. Considering the end-of-year spending bill going through Congress right now, I am not holding my breath."

Inflation can be brought down quickly

"The Economist has an article on what the 1980s can teach us about solving the inflation problem:

So the experience of the 1980s may become instructive. And once you dig into the history, the decade holds three tough lessons for today’s policymakers. First, inflation can take a long time to come down. Second, defeating inflation requires the participation not just of central bankers, but other policymakers too. And third, it will come with huge trade-offs. The question is whether today’s policymakers can navigate these challenges.

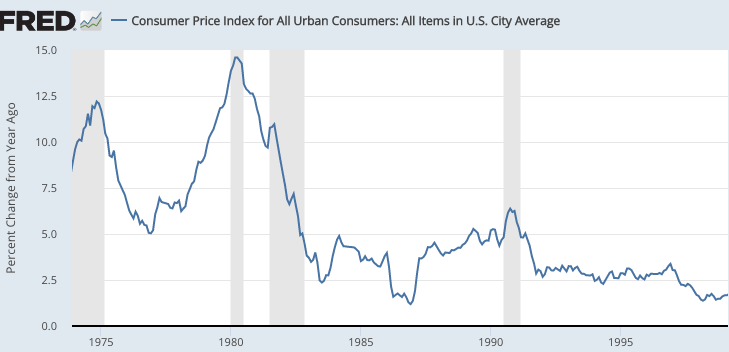

The first two points are incorrect, at least for the US. Inflation was brought down relatively quickly after Paul Volcker finally adopted a tight money policy in mid-1981. The 12-month inflation rate fell from 14.3% in June 1981 to 3.8% in December 1982. And this was done with no help from fiscal policy, as the newly elected President Reagan slashed taxes and boosted military spending. Some Keynesian economists (wrongly) suggested that this fiscal stimulus would lead to high inflation. (There was a modest payroll tax increase in 1983, but by that time the inflation problem had already been solved.)

The Economist is right about the trade-offs. When inflation has become entrenched, bringing it down to much lower levels can cause a recession. It’s too soon to know what will happen in 2023 (our current inflation problem is less severe than in 1981), but the risk of recession is clearly higher than during a normal year.

PS. You can argue that Reagan’s tax cuts made the disinflation less painful than otherwise, but they did not cause the disinflation."

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

AG confirms billions in COVID spending was poorly targeted—continuing a troubling trend

By Jake Fuss of The Fraser Institute.

"According to Canada’s auditor general, which released a report last week on federal spending during the pandemic, COVID programs were delivered quickly but were poorly targeted. Unfortunately, wasteful and poorly targeted spending has been a habit for the federal government in recent years.

The report identified 51,049 businesses that unnecessarily received wage subsidies from Ottawa during COVID mainly through Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), which was designed to give employers who suffered revenue declines a subsidy of up to 75 per cent on their payroll costs.

Specifically, the tax filings of these employers “did not demonstrate a sufficient revenue drop to be eligible for the subsidy.” Put differently, Ottawa apparently gave nearly $10 billion to businesses that did not need the money. This raises serious questions about waste, transparency, and execution of the spending.

Moreover, the analysis also found that the federal government paid $4.6 billion in other COVID supports including Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) payments to ineligible Canadians, and recommended that the government further investigate the nature of at least $27.4 billion in additional COVID-related spending.

Again, though speed was needed during the early months of the pandemic to deliver payments to struggling families, particularly lower-income Canadians, a significant chunk of federal spending was clearly wasteful, poorly targeted, and gave support to those who did not need it.

While the scope of waste may shock many Canadians, it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

According to a 2020 study published by the Fraser Institute, an estimated 27.4 per cent of COVID-related spending (or $22 billion) was poorly targeted to households and individuals. And nearly $12 billion of total CERB spending was given to young people aged 15 to 24 living as dependents in households with incomes above $100,000.

Put simply, the Trudeau government repeatedly gave money to those who had little need for financial support during COVID because it failed to properly target the programs and was not sufficiently transparent or accountable during and after the spending took place.

But again, poor targeting is not something that only happened during COVID. Wasteful spending has become a feature rather than an anomaly in Ottawa.

Recently, the federal government doubled the GST credit for six months, to purportedly help Canadian families deal with high inflation. Eligible Canadians receive the credit each quarter to ostensibly offset the effects of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). But the program is poorly targeted, raising costs higher than they otherwise would be, and provides money to those who don’t necessarily need it.

For instance, according to a recent analysis, the federal government spent an estimated $340 million in 2021 providing the GST credit to young people who work part-time, go to school and live in high-income households. Providing more assistance to Canadians who are not in genuine need is a poor use of taxpayer dollars.

The auditor general report reveals some glaring problems with federal assistance during the pandemic, to the tune of billions of dollars of wasteful spending. But poor targeting and wasteful spending have become a common theme for Ottawa. Throwing money in every direction is not an effective strategy to help those in need."