"Every year the National Committee on Pay Equity (NCPE) publicizes “Equal Pay Day”

to bring public attention to the gender earnings gap. According to the

NCPE, “Equal Pay Day” falls this year tomorrow on Tuesday, March 24

based on an approximate 20% difference in unadjusted, raw median annual

earnings according to the Census Bureau. Tomorrow’s “feminist day of

grievance” therefore allegedly represents how far into 2021 women will

have to continue working to earn the same income that their male

counterparts and co-workers earned in 2020, supposedly for working side-by-side with men doing the exact same job working the exact same number of hours per week with the same education and the exact same number of years of continuous, uninterrupted work experience.

Inspired by Equal Pay Day, I introduced “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” in 2010 to bring public attention to the huge gender disparity in work-related deaths every year in the United States. “Equal Occupational Fatality Day”

tells us how many years and days into the future women will be able to

continue to work before they will experience the same number of

occupational fatalities that occurred for men in the previous year.

Last December, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released final data

on workplace fatalities in 2018, and a new “Equal Occupational Fatality

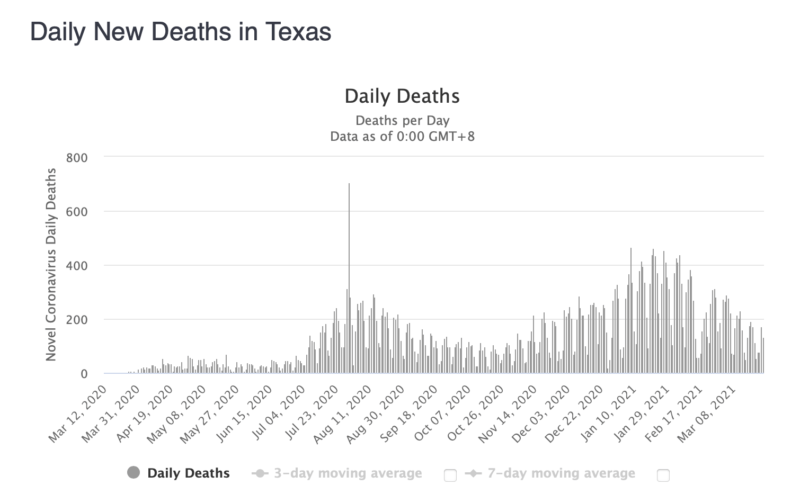

Day” can now be calculated. As in previous years, the top graphic above

shows the significant gender disparity in workplace fatalities in 2019:

4,896 men died on the job (91.8% of the total) compared to only 437

women (8.2% of the total). The “gender occupational fatality gap” in 2019 was again considerable — more than 11 men died on the job for every woman who died while working.

Based on the BLS data for 2019 for workplace fatalities by gender

(and assuming those figures will be approximately the same in 2020), the

next “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” will occur ten

years from now – on May 9, 2031. That date symbolizes how far into the

future women will be able to continue working before they experience

the same loss of life that men experienced in 2020 from work-related

deaths. Because women tend to work in safer occupations than men on

average (frequently reflected in lower wages), they have the advantage

of being able to work for a decade longer than men before they

experience the same number of male occupational fatalities last year.

Economic theory tells us that the “gender occupational fatality gap” explains part of the “gender earnings gap”

because a disproportionate number of men work in higher-risk, but

higher-paid occupations like iron and steelworkers (97.8% male) roofers

(97.4% male), construction trades (96.6%) and electric power line

workers (95.9% male); see BLS data here. The bottom chart above shows that for the 10 most dangerous US occupations in 2019 based on fatality rates per 100,000 workers by industry and occupation

men represented more than 90% of the workers in nine of those 10

occupations (all except “Farmers and Ranchers”) and more than 96% of the

workers in five of the 10 occupations.

On the other hand, women far outnumber men in relatively low-risk

industries, sometimes with lower pay to partially compensate for the

safer, more comfortable indoor office environments in occupations like

office and administrative support (70.9% female), education, training,

and library occupations (73.6% female), and healthcare (75.4% female).

The higher concentrations of men in riskier occupations with greater

occurrences of workplace injuries and fatalities suggest that more men

than women are willing to expose themselves to work-related injury or

death in exchange for higher wages. In contrast, women on average, more

than men, prefer lower-risk occupations with greater workplace safety

and are frequently willing to accept lower wages for the reduced

probability of work-related injury or death. The reality is that men and

women demonstrate clear gender differences when they voluntarily select

the careers, occupations, and industries that suit them best, and those

voluntary choices contribute to differences in earnings that have

nothing to do with gender discrimination.

Bottom Line: Groups like the NCPE use “Equal Pay

Day” to promote a goal of perfect gender pay equity, probably not

realizing that they are simultaneously advocating a significant increase

in the number of women working in higher-paying, but higher-risk

occupations like roofing, construction, farming, and mining. The reality

is that a reduction in the gender pay gap would require gender parity

by occupation, and would therefore come at a huge cost: several thousand

more women will be killed each year working in dangerous occupations.

Further, the proponents of “Equal Pay Day” are promoting a

statistical falsehood by suggesting that women working side-by-side with

men in the same occupation for the same company are making something

like 20% less than their male counterparts, which causes them to have to

work an additional three months to achieve “equal pay.” The NCPE’s

statement that “because women earn less, on average than men, they must

work [20%] longer for the same amount of pay,” implies that gender wage

discrimination is the only factor behind the gender pay/earnings gap. Of

course, that would imply that some corrective action by government is

necessary to address the gender pay gap, even though most studies find

that there is no gender earnings gap after factors like hours worked,

child-birth and child care, career interruptions, and individual choices

about industry and occupation are considered. For example, a 2009 study by the Department of Labor concluded:

This study leads to the unambiguous conclusion that the

differences

in the compensation of men and women are the result of a multitude of

factors and that the raw wage gap should not be used as the basis to

justify corrective action. Indeed, there may be nothing to correct. The

differences in raw wages may be almost entirely the

result of the individual choices being made by both male and female

workers.

Conclusion: I hereby suggest, that after adjusting

for all factors that contribute to gender differences, “Equal Pay Day”

actually fell during the first week of this year. Or maybe the second

week of January…. but NOT the fourth week of March. Women should be

embarrassed by the statistical fairy tale that is annually promoted on

their behalf by NCPE’s “Equal Pay Day.” The annual “Feminist Victimology

Day” suggests that widespread and unchecked gender discrimination in

the labor market burdens them with three months of additional work to

earn the same amount as their male counterparts earned in the previous

year – when that’s not even remotely true.

Finally, here’s a question I pose to the NCPE every year: Closing the “gender earnings gap” can really only be achieved by closing the “occupational fatality gap.” Would achieving the goal of perfect earnings equity really be worth the loss of life for thousands of additional women each year who would die in work-related accidents?

Related: From the Wall Street Journal‘s editorial last year “Equal Death Day“:

Last Tuesday was “Equal Pay Day.” This unofficial holiday was first

declared in 1996 to protest the “wage gap” between the sexes. In the

latest data, according to proponents, American women who work full time

earned only 80 cents for each $1 earned by men. Hence, to catch up with a

man’s pay from 2018, a woman must keep working until roughly April 2.

The problem with comparing this raw, aggregate data is well

documented. Women on average go into lower-paying fields, such as

education. Mothers are likelier than fathers to choose flexibility over

career advancement. Men tend to work slightly more hours on the job.

………

The broader point is that humanity is complicated. Millions of men

and women make their own choices about which careers, jobs and family

structures will work best for them. Who but a committed social engineer

could demand that their median pay precisely match?

Related: Here’s a quote from Camile Paglia in 2013 writing in TIME (“It’s a Man’s World and It Always Will Be“)

about men’s important, but mostly underappreciated role in the labor

market and the importance of their willingness to do the dangerous work

that makes us all better off:

Indeed, men are absolutely indispensable right now, invisible as it

is to most feminists, who seem blind to the infrastructure that makes

their own work lives possible. It is overwhelmingly men who do the

dirty, dangerous work of building roads, pouring concrete, laying

bricks, tarring roofs, hanging electric wires, excavating natural gas

and sewage lines, cutting and clearing trees, and bulldozing the

landscape for housing developments. It is men who heft and weld the

giant steel beams that frame our office buildings, and it is men who do

the hair-raising work of insetting and sealing the finely tempered

plate-glass windows of skyscrapers 50 stories tall.

Every day along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, one can watch the

passage of vast oil tankers and towering cargo ships arriving from all

over the world. These stately colossi are loaded, steered and off-loaded

by men. The

modern economy, with its vast production and distribution network is a

male epic, in which women have found a productive role — but women were

not its author. Surely, modern women are strong enough now to give

credit where credit is due!

Related: “The ’77 Cents on the Dollar’ Myth About Women’s Pay,” my Wall Street Journal op-ed with Andrew Biggs in 2014:

While the BLS reports that full-time female workers earned 81% of

full-time males, that is very different than saying that women earned

81% of what men earned for doing the same jobs, while working the same

hours, with the same level of risk, with the same educational background

and the same years of continuous, uninterrupted work experience, and

assuming no gender differences in family roles like child care. In a

more comprehensive study that controlled for most of these relevant

variables simultaneously—such as that from economists June and Dave

O’Neill for the American Enterprise Institute in 2012—nearly all of the

23% raw gender pay gap cited by Mr. Obama can be attributed to factors

other than discrimination. The O’Neills conclude that, “labor market

discrimination is unlikely to account for more than 5% but may not be

present at all.”

These gender-disparity claims are also economically illogical. If

women were paid 77 cents on the dollar, a profit-oriented firm could

dramatically

cut labor costs by replacing male employees with females. Progressives

assume that businesses nickel-and-dime suppliers,

customers,

consultants, anyone with whom they come into contact—yet ignore a great

opportunity to reduce wages costs by 23%. They don’t

ignore the opportunity because it doesn’t exist. Women are not in fact

paid 77 cents on the dollar for doing the same work as men.

and “Equal Pay Day Commemorates a Mythical Gender Pay Gap” my Real Clear Markets op-ed with Andrew Biggs in 2017:

Proponents of the gender pay gap myth would have you believe that any

difference in earnings between men and women is the result of gender

pay discrimination. The reality is that men and women are different –

they gravitate to different college majors, they have different levels

of work experiences, they play different family roles, and they often

work in very different types of jobs. It would be inexplicable to

imagine that despite those many differences men and women would earn

precisely the same amounts. It would also be completely unrealistic to

suggest that the 20% difference in annual earnings is exclusively or

even largely the result of gender discrimination. But to celebrate Equal

Pay Day, those are some of the statistical fairy tales that you have to

accept."