"recent studies err in the same way as De Loecker and Eeckhout’s earlier work by not properly accounting for marketing and management costs. Marketers and managers are skilled labor, so if we omit them from our calculations, we’ll mistakenly classify payments to workers as excess profits. The De Loecker and Eeckhout method does precisely this by excluding these costs entirely in estimating market power.

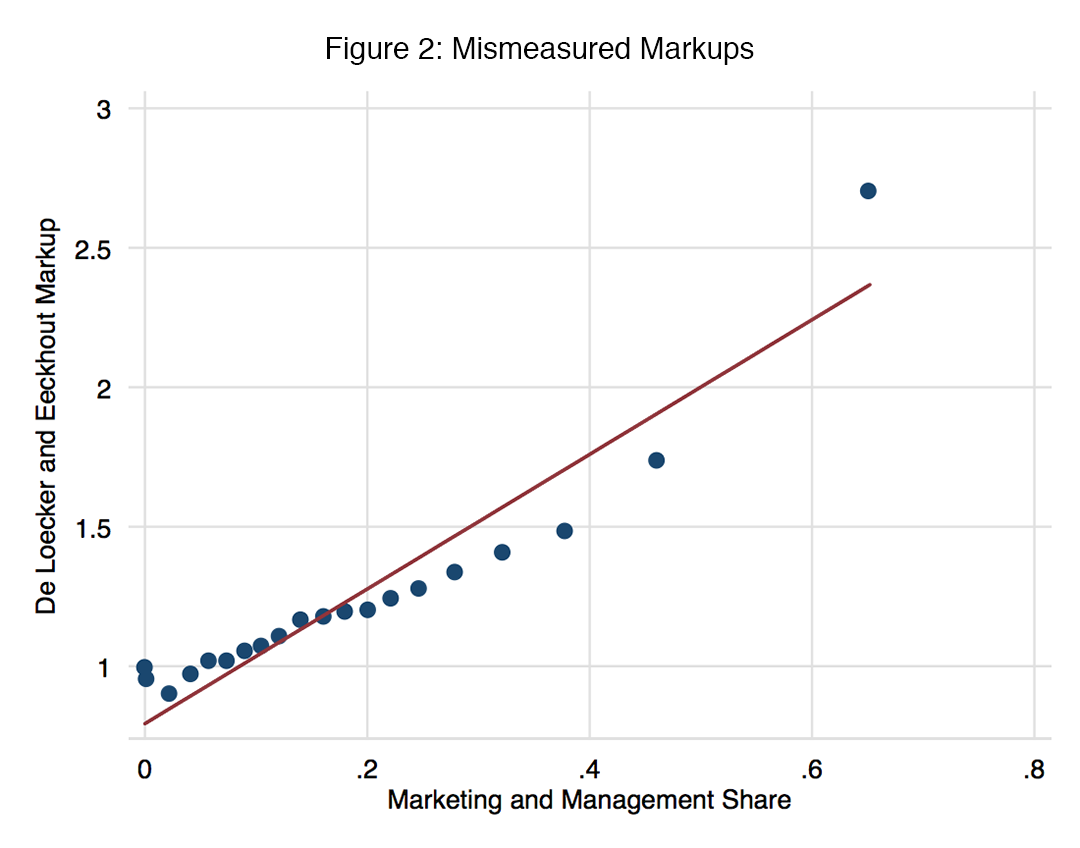

As I document in my own work on US firms, a direct artifact of this omission is a large markup. Figure 2 plots the correlation between markup estimates using this method, and the share of expenses contributed by marketing and management. The strong correlation shows that where these authors would infer significant market power is exactly where we see a greater contribution from these costs.

Moreover, these costs are a rising share of expenses for US public firms, so excluding them makes the problem worse and worse over time. I find that including them in market power measurement substantially flattens any trend in US markups; instead of skyrocketing, market power has remained relatively stable for the last 70 years, and is about as high today as in the 1950s.

The rise of marketing and management suggests that the middle-class squeeze is an outcome of changes in technology. Labor economists have collected a wealth of evidence consistent with this hypothesis (see here for a review). It also squares with the rise in profits: technological change that increases returns to scale would also increase profit rates, since costs would be lower for all the units up to the marginal unit. Firms are shifting the way they produce, and only workers who can keep pace end up benefiting.

If marketing and management are also a rising share of expenses for non-US firms, then the markup estimates of these global market power papers will understate costs increasingly over time, and thus overstate markups increasingly over time. De Loecker and Eeckhout (2018) do not address this point. Diez, Leigh, and Tambunlertchai (2018) make an attempt, but they do so in a way that can only adjust the level of markups, not the trend."

"Other prominent work hypothesizes that the rise in US industrial concentration is a consequence of weakened US antitrust enforcement. If market power is increasing even in Europe, where antitrust enforcement has remained relatively unchanged, then we would need drastic competition policy reform to affect curb existing market power. However, if market power is stable, then we need to look elsewhere for culprits of stagnant wages and rising concentration, such as how trade and technology impact markets."

"Ultimately, since sales and expenses are observable, the technical debate centers on what’s the right measure of flexible inputs, and how we estimate its elasticity. Specifically, do we include market and management costs as part of flexible inputs? And how should we account for them otherwise?

"My proposed solution is to answer yes to this first question: treat marketing and management costs as part of flexible inputs. A flexible input is one that firms can change to affect output without big adjustment costs. The simple economics argument here is that hiring skilled marketers or managers increases sales, and it’s pretty easy to do that within a year’s time. If you accept these premises, then you should mark these costs as flexible.

If you’re still skeptical, my paper supports these premises with two reassuring pieces of empirical evidence. First, markup estimates including marketing and management costs aren’t sensitive to the choice of shorter or longer production horizons. Even if these costs weren’t already flexible in the short-run, they would be flexible in the long-run. Second, the expenses change smoothly within a firm. If these costs weren’t flexible, firms would change them in bursts. Overall, my proposed solution produces a much flatter trend in US data, and may affect global estimates similarly."

"As a final note for perspective, Simcha Barkai, one of the first academics to sound the market power alarm, makes this excellent point in his recent work with Seth Benzell:

The profits implied by De Loecker and Eeckhout (2017) exceed 80% of gross value added in 2014. These implied profits are implausibly high: so long as capital costs are non-negative, profits can’t exceed gross value added less compensation of employees. This bound implies that profits can’t exceed 42% of gross value added.If the De Loecker and Eeckhout markups were representative of the overall US economy, Barkai’s back-of-the-envelope implies that 80 percent of GDP is going to economic rents, which leaves 20 percent for labor and capital. But labor alone is measured at over 40 percent. Of course, these estimates still rely on extrapolating public firms estimates to the overall economy. In my paper, I show that inference from public firm markups significantly overstates aggregate market power estimates, stressing that it’s important for future research to apply similar methods to administrative production datasets that include private firms."

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Not properly accounting for marketing and management costs means we’ll mistakenly classify payments to workers as excess profits

See What Current Research (Still) Gets Wrong about Market Power by James Traina at ProMarket (The blog of the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business). Excerpts:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.