"John Horton has written a novel paper that uses an experiment and a policy change in an online job market to understand the effects of the minimum wage. The job market in question is something like the Upwork platform where firms can post jobs and workers from anywhere in the world can post offers to work at an hourly wage to do tasks such as computer programming, data entry, design and transcription. Typically workers are hired for a week or two.

Horton was able to implement a minimum wage by simply not allowing a worker to offer to work at less than the minimum wage for a randomly chosen set of jobs.

During the experimental period, firms posting an hourly job opening were immediately assigned to an experimental cell. The experiment consisted of four experimental cells: a control group with the platform status quo of no minimum wage, which received 75% of the sample (n = 121, 704), and three active treatment cells, which split the remaining 25% of the sample. A total of 159,656 job openings were assigned. Neither employers nor workers were told they were in an experiment. The active treatments had minimum wages of $2/hour in MW2 (n = 12, 442), $3/hour in MW3 (n = 12, 705), and $4/hour in MW4 (n = 12, 805).Horton found that the minimum wage did reduce hiring, especially in low-wage job categories when the minimum wage was high relative to the median wage. The hiring reduction was measurable but, consistent with previous research, not large. All the work on the platform, however, is logged through the software so Horton also has very good data on hours worked and here the story is quite different. The minimum wage substantially reduced hours worked.

A higher minimum wage likely causes firms to scale back projects but that seems somewhat inconsistent with the small effect on hiring (fixed costs of hiring would suggest fewer hires and fewer hours but perhaps more hours per hire.) Horton finds another factor explains the reduction in hours worked. At a higher minimum wage, firms are careful to hire more productive workers. He finds that about half of the decline in hours can be explained by substitution towards higher productivity workers. Previous studies have found suggestive effects along these lines. For example, Giuliano 2013 found that the higher minimum wages could shift teenage employment to teenagers from more affluent regions who were likely more skilled and less likely to quit. Horton finds similar demographic effects as hiring shifts away from Bangladeshi workers and towards US workers but since his data on productivity is much cleaner than in previous studies there is less need to rely on demographic correlates of productivity.

In part (it seems) due to the experiment, the job-platform later instituted a $3 per hour minimum wage for all jobs. Horton is thus able to supplement his experimental results with analysis of a policy change in the same environment. Consistent with the experimental result, the imposition of the minimum wage across the board caused substantial declines in hours worked with little effect on hiring overall but a big effect on the lowest-wage workers who found that their probability of being hired dropped substantially after the minimum wage was imposed."

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

The Minimum Wage in an Online Job Market

From Alex Tabarrok Marginal Revolution.

Rich Nations that Enact Big Government Don’t Stay Rich

By Daniel J. Mitchell.

"Move over, Crazy Bernie, you’re no longer the left’s heartthrob. You’ve been replaced by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, an out-of-the-closet socialist from New York City who will enter Congress next January after beating a member of the Democratic leadership.

Referring to the boomlet she’s created, I’ve already written about why young people are deluded if they think bigger government is the answer, and I also pointed out that Norway is hardly a role model for “Democratic socialism.”

And in this brief snippet, I also pointed out she’s wrong to think that you can reduce corporate cronyism by giving government even more power over the economy.

But there’s a much bigger, more important, point to make.

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez wants a radical expansion in the size of the federal government. But, as noted in the Washington Examiner, she has no idea how to pay for it.

Consider…how she responded this week when she was asked on “The Daily Show” to explain how she intends to pay for her Democratic Socialism-friendly policies, including her Medicare for All agenda. “If people pay their fair share,” Ocasio-Cortez responded, “if corporations paid—if we reverse the tax bill, raised our corporate tax rate to 28 percent … if we do those two things and also close some of those loopholes, that’s $2 trillion right there. That’s $2 trillion in ten years.” She should probably confer with Democratic Socialist-in-arms Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., whose most optimistic projections ($1.38 trillion per year) place the cost of Medicare for All at roughly $14 trillion over a ten-year period. Two trillion in ten years obviously puts Ocasio-Cortez a long way away from realistically financing a Medicare for All program, which is why she also proposes carbon taxes. How much she expects to raise from this tax she didn’t say.To be fair, Bernie Sanders also didn’t have a good answer when asked how he would pay for all the handouts he advocated.

To help her out, some folks on the left have suggested alternative ways of answering the question about financing.

I used to play basketball with Chris Hayes of MSNBC. He’s a very good player (far better than me, though that’s a low bar to clear), but I don’t think he scores many points with this answer.

Indeed, Professor Glenn Reynolds of the University of Tennessee Law School required only seven words to point out the essential flaw in Hayes’ approach.

Simply stated, there’s no guarantee that a rich country will always stay rich.

I wrote earlier this month about the importance of long-run economic growth and pointed out that the United States would be almost as poor as Mexico today if growth was just one-percentage point less every year starting in 1895.

That was just a hypothetical exercise.

There are some very sobering real-world examples. For instance, Nima Sanandaji pointed out this his country of Sweden used to be the world’s 4th-richest nation. But it has slipped in the rankings ever since the welfare state was imposed.

Venezuela is another case study, as Glenn Reynolds noted.

Indeed, according to NationMaster, it was the world’s 4th-richest country, based on per-capita GDP, in 1950.

For what it’s worth, I’m not familiar with this source, so I’m not sure I trust the numbers. Or maybe Venezuela ranked artificially high because of oil production.

But even if one uses the Maddison database, Venezuela was ranked about number 30 in 1950, which is still impressive.

Today, of course, Venezuela is ranked much lower. Decades of bad policy have led to decades of sub-par economic performance. And as Venezuela stagnated, other nations become richer.

So Glenn’s point hits the nail on the head. A relatively rich nation became a relatively poor nation. Why? Because it adopted the statist policies favored by Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

I want to conclude, though, with an even better example.

More than seven years ago, I pointed out that Argentina used to be one of the world’s richest nations, ranking as high as number 10 in the 1930s and 1940s (see chart below).

Sadly, decades of Peronist policies exacted a heavy toll, which dropped Argentina to about number 45 in 2008.

Well, I just checked the latest Maddison numbers and Argentina is now down to number 62. I was too lazy to re-crunch all the numbers, so you’ll have to be satisfied with modifications to my 2011 chart.

The reverse is true as well. There are many nations that used to be poor, but now are rich thanks to the right kind of policies.

The bottom line is that no country is destined to be rich and no country is doomed to poverty. It’s simply a question of whether they follow the right recipe for growth and prosperity."

Labels:

Capitalism,

Socialism. Private Property,

Systems

Monday, July 30, 2018

The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System

By Charles Blahous of Mercatus.

"The leading current Senate bill to establish single-payer health insurance in the United States is that of Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT). It’s called the Medicare for All Act, or M4A. The desirability and practicality of this kind of healthcare system will depend in large measure on cost—on what American taxpayers would have to pay for it.

Charles Blahous puts a price on Sanders’s proposed legislation in “The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System.” These are his key findings.

M4A Would Place Unprecedented Strain on the Federal Budget

By conservative estimates, this legislation would have the following effects:

These estimates are conservative because they assume the legislation achieves its sponsors’ goals of dramatically reducing payments to health providers, in addition to substantially reducing drug prices and administrative costs.

- M4A would add approximately $32.6 trillion to federal budget commitments during the first 10 years of its implementation (2022–2031).

- This projected increase in federal healthcare commitments would equal approximately 10.7 percent of GDP in 2022. This amount would rise to nearly 12.7 percent of GDP in 2031 and continue to rise thereafter.

A doubling of all currently projected federal individual and corporate income tax collections would be insufficient to finance the added federal costs of the plan.

M4A’s Dramatic Federal Cost Increase Arises from Several Factors

- First and foremost, the federal government would become responsible for financing nearly all current national health spending, including individual private insurance and state spending.

- M4A would increase federal health spending on the currently uninsured as well as those who now carry insurance by providing first-dollar coverage of their healthcare expenditures across the board, without deductibles or copayments.

- M4A would expand the range of services covered by federal insurance (for example, dental, vision, and hearing benefits).

- M4A would dramatically expand the demand for healthcare services, consistent with economics research findings that the more of an individual’s health costs are covered by insurance, the more services they tend to buy, irrespective of the services’ efficacy and value.

We Do Not Know How Much M4A Would Disrupt the Availability and Quality of Health Services

M4A would markedly increase the demand for healthcare services while simultaneously cutting payments to providers by more than 40 percent, reducing payments to levels that are lower on average than providers’ current costs of providing care. It cannot be known how much providers will react to these losses by reducing the availability of existing health services, the quality of such services, or both."

Venezuela’s inflation will hit 1 million percent. Thanks, socialism

By Megan McArdle. Excerpt:

"Why did Venezuela embark on the road to destruction? And why does the government stay on it while the citizenry slowly starves?

In a word, socialism. After his election as president in 1998, Hugo Chávez pursued an increasingly aggressive socialist agenda, one that continued under his 2013 successor, Nicolás Maduro. Chávez nationalized foreign oil fields, along with other significant portions of the economy, and diverted investment funds from PDVSA, the state-owned oil company, into vastly expanded social spending.

Unfortunately, Venezuela’s heavy, sour crude oil was unusually hard to get out of the ground. Continual investment was needed to keep it flowing. So was the expertise of the banished foreign owners and the PDVSA engineers Chávez had purged for opposing this scheme. Production plunged; the only thing that kept Venezuela from disaster was a decade-long oil boom that offset falling production with rising prices.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis that crushed global demand for oil, followed by the onrush of U.S. shale oil, driving prices down further. And no one would loan money to Venezuela that couldn’t be repaid in oil. Meanwhile, unwilling to admit that socialism had failed, Venezuela made a fateful turn to the central bank.

Now, one could say that this is not an indictment of socialism so much as the particular Venezuelan implementation of it. But it’s striking how the precarious economics of socialism, including hyperinflations, are tied to petroleum. Many of the notable hyperinflations in history were tied to the collapse of the Soviet Union. And the story of the Soviet collapse is also a story about oil.

Central planning had wrecked the Soviets’ grain production by the 1960s, and collectivized industry didn’t produce anything that the rest of the world wanted to buy, leaving the Soviets unable to obtain hard currency to import grain. Oil sales propped up the Soviets until the mid-1980s , when prices crashed as new sources of oil came online (sound familiar?). The Soviet leadership was forced to liberalize to rescue the economy. The U.S.S.R.’s collapse soon followed.

Socialism, in other words, often seems to end up curiously synonymous with “petrostate.” The new breed of socialists cites Norway as a model, but saying “we should be like Norway” is equivalent to saying “we should be a very small country on top of a very large oil field.”

Without brute commodity extraction, you need capitalist markets to generate a surplus to distribute, which is why Denmark’s and Sweden’s economies have more in common with the U.S. system than with the platform of the Democratic Socialists of America. And as both Venezuela and the Soviet Union show, even oil may not be enough to save socialism from itself."

Sunday, July 29, 2018

Rare Earths Crisis in Retrospect

By Marian L. Tupy of Cato.

"On April 10, a team of 21 Japanese scientists discovered a 16 million ton patch of mineral-rich deep sea mud near Minami-Tori Island, which lies 790 miles off the coast of Japan. The patch appears to contain a wealth of rare earth elements, including 780 years’ worth of yttrium, 620 years’ worth of europium, 420 years’ worth of terbium and 730 years’ worth of dysprosium. This find, the scientists concluded, “has the potential to supply these materials on a semi-infinite basis to the world.”

The happy discovery provides us with an opportunity to revisit the last crisis over the availability of natural resources and recall the ingenuous ways in which humanity tackled that particular problem.

In September 2010, a Chinese fishing trawler and a Japanese coast guard vessel collided in waters disputed by the two countries. The Japanese detained the captain of the Chinese vessel and China responded by halting all shipments of rare earths to Japan. The latter used the imported metals in a number of high-tech industries, including production of magnets and Toyota Priuses. At the time of the embargo, China accounted for 97 percent of rare earths production and a large part of the processing business. Predictably, global panic ensued.

In the United States, which uses the rare elements in its defense systems, wind turbines and electric cars, the great and the good rang the alarm bells. Writing in The New York Times, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman opined,

“You really have to wonder why nobody raised an alarm while this was happening, if only on national security grounds. But policy makers simply stood by as the U.S. rare earth industry shut down…. The result was a monopoly position exceeding the wildest dreams of Middle Eastern oil-fueled tyrants. Couple the rare earth story with China's behavior on other fronts — the state subsidies that help firms gain key contracts, the pressure on foreign companies to move production to China and, above all, that exchange-rate policy — and what you have is a portrait of a rogue economic superpower, unwilling to play by the rules. And the question is what the rest of us are going to do about it.”

The U.S. Congress convened a hearing on “China’s monopoly on rare earths: Implications for U.S. foreign and security policy,” with Rep. Donald Manzullo (R-IL) declaring, “China’s actions against Japan fundamentally transformed the rare earths market for the worse. As a result, manufacturers can no longer expect a steady supply of these elements, and the pricing uncertainty created by this action threatens tens of thousands of American jobs.” Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA) argued that “Chinese control over rare earth elements gives them one more argument as to why we should kowtow to China,” while a report by the Government Accountability Office warned that “rebuilding a U.S. rare earth supply chain may take up to 15 years.”

So, what really happened?

In a 2014 Council on Foreign Relations report, Eugene Gholz, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, revisited the crisis and found that the Chinese embargo proved to be a bit of a dud. Some Chinese exporters got around the embargo by using legal loopholes, such as selling rare earths after combining them with other alloys. Others smuggled the elements out of China outright. Some companies found ways to make their products using smaller amounts of the elements while others “remembered that they did not need the high performance of specialized rare earth[s] ... they were merely using them because, at least until the 2010 episode, they were relatively inexpensive and convenient.” Third, companies around the world started raising money for new mining projects, ramped up the existing plant capacities and accelerated plans to recycle rare earths.

The market response, then, diffused the immediate crisis when prices of rare earths, which spiked in 2011, came down again. In the long run, as the Minami-Tori find suggests, future supply of rare earths seems promising.

The broader lesson from the rare earths episode is this: human beings are intelligent animals who innovate their way out of shortages, real and imagined. We have done so many times before. In some cases, we have relied on greater efficiency. An aluminum can, for example, weighed about 3 ounces in 1959. Today, it weighs less than half an ounce. In other cases, we have replaced hard to come by resources with those that are more plentiful. Instead of killing whales for lamp oil, for instance, we burn coal, oil and gas. Finally, we have gotten better at identifying natural resource deposits. Thus, contrary to a century of predictions, our known resources of fossil fuels are higher than ever.

As such, there is no a priori reason why human ingenuity and market incentives should not be able to handle future shortages as well."

6 out of the 10 worst famines of the 20th century happened in socialist countries

See Central Planning and Hunger: a Quick Reminder by Marian L. Tupy.

"Socialism is back in vogue, especially among America’s college-educated youth. They are too young to remember the Cold War and few study history. It is, therefore, timely to remind the millennials of what socialism wrought – especially in some of the world’s poorest countries.

Those of us who remember the early 1980s will always remember the images of starving Ethiopian children. With bellies swollen by kwashiorkor and eyes covered with flies, these were the innocent victims of the Derg – a group of Marxist militants who took over the Ethiopian government and used starvation to subdue unruly parts of the country.

Between 1983 and 1985, some 400,000 people starved to death. In 1984, Derg earmarked 46 percent of the gross domestic product for military spending, thereby creating the largest standing army in Africa. In contrast, spending on health fell from 6 percent of GDP in 1973 to 3 percent in 1990.

Predictably, the Derg blamed the ensuing famine on drought, although the rains failed many months after the food shortages began. In 1991, the Derg was overthrown and its leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, escaped to Zimbabwe, where he lives, under government protection and at the taxpayers’ expense, to this day.

Speaking of Zimbabwe, in 1999, Robert Mugabe, the 92-year-old Marxist dictator who came to power in 1980, embarked on a catastrophic “land reform” program. The program saw the nationalization of privately-held farmland and the expulsion of non-African farmers and businessmen. The result was a collapse of agricultural output, the second highest hyperinflation in recorded history that peaked at 89.7 sextillion or 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000 percent per year and an unemployment rate of 94 percent.

Thousands of Zimbabweans died of hunger and disease despite massive international help. As was the case in Ethiopia, the government of Zimbabwe blamed the weather, stole much of the aid money, and denied food and medicine to its political opponents. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

I was reminded of that parade of horribles when I came across Benjamin Zycher’s table of the greatest famines of the 20th century. As Zycher notes, six out of the 10 worst famines happened in socialist countries. Other famines, including those in Nigeria, Somalia and Bangladesh, were partly a result of war and partly a result of a government’s economic mismanagement.

The American students growing interested in “socialism” today are too young to remember what the world actually looked like the last time socialism held sway. In their lifetimes, famine has all but disappeared. Today, there is not a single ongoing case of famine in the world – not even in war-torn places like Syria.

Why did famines disappear? First, because agricultural production is at an all-time high and food has been getting cheaper, not dearer. Between 1960 and 2015, the world’s population increased by 143 percent. Over the same time period, the price of food has gone down by 22 percent. Second, humanity has grown richer and can afford to buy more food. Over the last 55 years, the real average annual per capita income in the world rose by 163 percent. Third, communications and transport have massively improved and it is now possible to deliver food aid anywhere in the world in a relatively short time. Fourth, globalization and trade ensure that food can be purchased by anyone, anywhere.

Africa has been the main beneficiary of that salutary development. In 1961, Africans consumed 1,993 calories per person per day. In 2011, which is the last year for which the World Bank provides data, they consumed 2,618 calories. Globally, food consumption increased from 2,196 calories to 2,870 calories. Even in Ethiopia, food consumption has increased. In 1993, two years after the overthrow of the Derg, Ethiopians consumed 1,508 calories per person per day. In 2013, they consumed 2,131 calories.

Zimbabwe, which still suffers from Marxist rule, has not been so lucky. In 1961, Zimbabweans consumed 2,115 calories per person per day. By 2013, that number fell to 2,110.Wherever it has been tried, from the Soviet Union in 1917 to Venezuela in 2015, socialism has failed. Socialists have promised a utopia marked by equality and abundance. Instead, they have delivered tyranny and starvation. Young Americans should keep that in mind."

Saturday, July 28, 2018

See Standing Rock Redux. WSJ editorial.

"The proposed Line 3 would replace a deteriorating pipeline built in the 1960s that moves Alberta crude oil through a sliver of North Dakota and across Minnesota to Wisconsin. Enbridge estimates the old pipeline would require some 900 repairs by 2025 and 6,000 over the next 15 years, and it’s operating at about half capacity due to safety concerns.

The new Line 3 would benefit from more than 50 years of pipeline innovation. The old pipeline was forged using flash welding, which introduces impurities into steel that can cause cracks and corrosion.

Today’s double-submerged arc welding keeps pipeline steel clean and strong. To prevent rust, the new Line 3 would be coated in fusion-bonded epoxy. That’s a big improvement over the polyethelyne tape twisted around the old pipeline like hockey-stick wrap. The new pipeline would also feature automated valves, sophisticated leak-detection systems and 24/7 monitoring.

Thanks to such technological advances, pipelines now deliver oil safely 99.999% of the time, according to a 2017 report by the Association of Oil Pipelines and the American Petroleum Institute. Last year 72% of spills occurred in contained units on the operators’ property. And 70% of pipeline spills are less than a cubic meter, says Canada’s Fraser Institute."

"Trucks and trains are the alternatives to pipelines, but they’re more dangerous and carbon-intensive. Between 16.5 million and 23.1 million gallons of Bakken crude pass through Minnesota by rail each day. The state’s Department of Transportation has warned that this heavy train traffic routinely delays emergency-response vehicles and “poses a threat of catastrophic fire in the event of a derailment and rupture of some of the tank cars.” A recent derailment 15 miles south of the Minnesota border spilled 230,000 gallons of oil, contaminating two rivers."

Labels:

Energy,

Environment,

Regulation,

Unintended Consequences

Bryan Caplan on non-compete clauses

See The Dynamic Case for Non-Compete.

"Here’s Peter Mannino’s Featured Comment on my recent post:

Isn’t the entire case against non-compete clauses exactly that they stifle dynamic efficiency? Imagine if the traitorous 8 couldn’t leave Shockley to found Fairchild semiconductors, or Noyce and Moore couldn’t leave Fairchild to found Intel. California’s hostility to non-compete’s is one reason why we have a tech sector… I guess the problem is that some business practices prevent the world from being a place where “entrepreneurs know they can profit as they please if they make their firm great.”Plenty of people do indeed make this case against non-compete clauses. But their effect on innovation is far more complicated than it looks.

Suppose you have a great new idea. To implement your idea, you have to share it with eight crucial employees. But once you share it, any of these employees can take their knowledge and found a new firm to compete with you.

In this scenario, non-compete contracts are actually a great way to foster competition. How? By reassuring businesses that if they invest in new ideas, their employees can’t steal them at the first opportunity. What’s the point of creating or implementing new ideas if your hired helpers can readily betray you?

If this argument seems odd, notice that it’s structurally identical to a simpler argument. For example: Wouldn’t it be great for innovation if every firm had to make all their business secrets publicly available for free? On the surface, this makes perfect sense: Every aspiring innovator could quickly learn everything that every existing innovator already knows. Cornucopia! On reflection, though, this would be dynamically disastrous. What’s the point of coming up with new ideas in the first place if you have to give them all away gratis?

Question: If I’m right, how can California be so innovative? My best guess is that existing non-compete clauses are so weakly enforced that there’s little de facto difference between the law in California and the law in any other state. And in any case, the legality of non-compete clauses is only one of many ingredients of dynamic efficiency. So why care about this one? Because, per the Sorites’ Paradox, even minor ingredients add up. Wise policy-makers will focus on enhancing overall dynamic efficiency whether or not any specific policy seems especially crucial."

Friday, July 27, 2018

Why do drug prices keep going up?

See Here’s a Plan to Fight High Drug Prices That Could Unite Libertarians and Socialists by Charles Silver and David A. Hyman. Charles Silver s an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute and a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. David A. Hyman is an adjunct scholar at Cato and a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center. Excerpt:

"Why do drug prices keep going up? For branded drugs, the short answer is that patents give drug companies monopolies, which they exploit to the fullest. An added factor is that our payment system often allows manufacturers to charge whatever they want.

Let’s start with monopolies. Give a business, any business, a monopoly and it will extract wealth from consumers by charging monopoly prices. And that is precisely what patents for drugs do: They give drug companies monopolies on the sales of new medications.

Even when the original patents have long-since expired, drug companies use various contrivances to keep prices high. The most common tactic is to obtain extensions on marketing exclusivity by means of secondary patents on superficial characteristics, such as pills’ coatings or formulas for timed-release.

Consider Lipitor, a cholesterol-fighting statin. An extension of its patent term and a second extension for pediatric testing gave Pfizer, Lipitor’s manufacturer, an additional 1,393 days of marketing exclusivity, during which it took in $24 billion more than if the drug had entered the generic category when originally scheduled.

Lockstep pricing — made possible because only a small number of manufacturers compete in many drug categories — is a problem too. Companies don’t compete for customers by undercutting other makers’ prices; rather, when one raises its prices, the others follow suit. Economic theory suggests we shouldn’t see this kind of behavior, but we do.

What can we do about these problems? Let’s start with generic drugs, because the problem in that category is the most straightforward. Many of the pricing problems in the generic drug market are directly attributable to insufficient competition. Substantial price hikes occur and stick because only one company makes a drug, or because manufacturers raise prices in lockstep. Illegal, anti-competitive conduct may underlie some of these problems, in which case aggressive antitrust enforcement is the answer.

But the US Food and Drug Administration also bears part of the blame. There is a backlog of pending applications from generic drug manufacturers that want to enter the market. Congress should give the FDA the resources it needs to process these applications more quickly. But until that happens, the FDA should give priority to applications for generics that have experienced price hikes.

Currently, the FDA follows a first-in, first-out approach to applications. A more consumer-friendly arrangement would move applications for drugs that have experienced significant price spikes to the head of the line. A bonus: Once incumbents realize that price hikes will result in fresh competition, they may be deterred from jacking up prices to begin with.

More broadly, policymakers should liberalize access to the US generic drug market by relaxing the FDA’s grip on entry. Currently, the FDA requires that it, and it alone, approve the safety of generic drugs. But why not let a company that qualifies to sell a generic drug in Canada, England, France, Israel, or other developed country sell the same drug in the United States — at least so long as a generic equivalent has already been approved by the FDA, and the 180 days of marketing exclusivity provided to that generic by the Hatch-Waxman Act has expired.

These countries have the expertise needed to protect their citizens from excessive risks and the desire to do so. Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) recently came out in support of a similar idea. If such a policy had been in effect, Martin Shkreli wouldn’t have been able to price-gouge anyone."

Unmaking Affirmative Action

By Stephen T. Asma. He is a professor of philosophy at Columbia College Chicago. Excerpts:

"This goal of increasing diversity was articulated in Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s Grutter v Bollinger (2003) endorsement of the Court’s earlier claim that student body diversity is a compelling state interest and justifies the use of race in university admissions. The moral reasoning is that greater campus diversity breaks stereotypes and xenophobia, and students will therefore emerge from these experiences with greater tolerance and less prejudice.

However, ‘diversity’ is a long way from the original purpose of affirmative action. President Lyndon Johnson’s policy (Executive Order 11246) started as a legitimate leg-up for black Americans—a boost for opportunity in employment. But the more recent logic of the courts, as well as the public imagination, contends that affirmative action will help white people think better thoughts about people of color. Integrated diversity creates contact, the thinking goes, and contact reduces prejudice. This moral argument appears to underpin the Supreme Court’s logic in the Grutter v. Bollinger case, where Justice O’Connor argued that race preference policies would be a necessary evil for only another 10 years (25 years from the original opinion). After that, presumably, we’ll be past racial discrimination."

"Prejudice is not as uniform as it used to be, and now we have micro-prejudices that cannot be legislated away; Puerto Rican Americans stereotype Mexican Americans, who stereotype African Americans, who stereotype Korean Americans, who stereotype Japanese Americans, who stereotype Chinese Americans, who stereotype Pakistani Americans, who stereotype Indian Americans, and so on. Trying to mitigate this inevitable mess of tribalism with a preferential and zero-sum admissions policy seems like a fool’s errand."

"In 1960, only 9 percent of immigrants were Latin American and 5 percent were Asian. Compare that with 2011 immigration, when 52 percent were Latin American and 28 percent Asian. The color question has changed in America and this has implications for the logic of affirmative action."

"For the Left, it would have been better to keep the argument focused on reparation for descendants of slaves, because that smaller net captures the correct demographic group. But this argument is problematic for other reasons, namely the historical distance between today’s African American students and slavery.

Switching away from race and toward an economic criterion for preferential treatment results in two improvements; poor kids get into elite schools and poor minorities are captured within the general economic criterion. However, as legal scholar Ronald Dworkin has argued, in consideration of the Texas case, it is not enough to get black students on campus in Texas—a task easily accomplished by an existing law that takes the top 10 percent of Texas high school students and therefore draws smart, poor, black students from geographically black high schools. Judge Alito suggested, while hearing the case, that this 10 percent rule sufficiently ensures the sought-after student diversity. But supporters of affirmative action, like Dworkin, argued that this would not be the right sort of diversity, because it would feed white stereotypes that blacks are poor. Supporters of affirmative action in Texas argued that the university should be encouraged to cherry-pick black students from middle- and upper-class backgrounds in order to break campus stereotypes.

This is a strange and dubious argument against an economic criterion. Using an economic criterion only creates the stereotyping problems that Dworkin described (i.e., most of the black kids on campus will be poor) if you think middle-class blacks are not competitive with middle-class whites. Some data (from a 2011 Pew Research report) seem to suggest a competitive wealth gap between whites and African-Americans who have similar middle-class educational backgrounds, but what is needed is data of the reverse relation. Do African-American students of middle class income brackets fail to qualify (via exams and other objective measures) for quality schools? If so, this would constitute a strange and mysterious failure, since there’s no firm evidence of genetic causes for such a disparity, and middle-class status usually means that the ‘nurturing’ or cultural ingredients for educational success have been provided (e.g., intact nuclear families that push education). If, on the other hand, middle-class families that prize education produce competitive students no matter what their racial status, then the only ethical problem left in college admissions is helping economically disadvantaged students of every race.

Perhaps what Justice O’Connor should have argued was not that “diversity” policies need 25 more years of legal protection (her actual argument), but that slavery reparation needs 25 more years of legal protection."

"When Asians score their way into all the slots at the good schools, will whites argue that they were discriminated against? Actually, Asian scholastic excellence is already so powerful that Asians have to be discriminated against to keep them from overpopulating competitive programs. William M. Chace, in his 2011 “Affirmative Inaction” essay in the American Scholar, tells of a Princeton study that analyzed the records of more than 100,000 applicants to three highly selective private universities. “They found that being an African-American candidate was worth, on average, an additional 230 SAT points on the 1600-point scale and that being Hispanic was worth an additional 185 points, but that being an Asian-American candidate warranted the loss, on average, of 50 SAT points.”"

"Liberals might object that Chinese people never had the hard times that blacks had in America, so they don’t deserve any special treatment. The descendants of the Chinese indentured laborers who built the transcontinental railroads would probably beg to differ, as would the descendants of the Los Angeles Chinese massacre and mass lynching of 1871. Moreover, what do we make of the Naturalization Act of 1870, that extended citizenship rights to African-Americans but denied them to Chinese on the grounds that they could never be assimilated and integrated into American society? Almost a century of anti-Chinese policies followed, punishing them and subjecting them to Jim Crow-like conditions. Also, a new study shows that income inequality for Asians has now surpassed the ratio for African-Americans, so the myth of Asian economic advantage is exposed.

The tangled criteria of (a) reparation for past injuries and (b) ‘breaking stereotypes’ (through increased diversity) is a very sticky wicket, because it radically opens the floodgates of equally reasonable complaints."

"‘breaking stereotypes’ is an over-inclusive criterion, and fails the strict scrutiny expectation that a law or policy be ‘narrowly tailored’ to achieve its goal or interest. Here we see the problem with basing today’s preferential treatment on histories of injury and victimization. Too many groups have been victims for the State to undo the damages. The medicine becomes worse than the disease it is intended to treat."

" a recent study looks at why Asian kids from poor families score better than rich white kids, and concludes that Asian family culture makes the difference. It’s not some genetic or innate cognitive advantage, but the family insistence that achievement comes from extreme effort—a longstanding emphasis in Confucian cultures. Of course, this is unlikely to be the only cause of academic excellence, but it can’t be ignored or trivialized either."

Thursday, July 26, 2018

The Challenge of Retraining Workers for an Uncertain Future

By Adam Thierer of Mercatus. Excerpt:

"The reality is, most worker retraining plans are little better than a dice-roll on the professions and job needs of the future. As I noted in my last book as well as in a paper with Andrea O’Sullivan and Raymond Russell, concerns about automation, AI, and robots taking all our jobs have put worker retraining concerns back in the spotlight in a major way. That has led many scholars, pundits, and policymakers to suggest that more needs to be done to address the skills workers will need going forward.

That impulse is completely understandable. But it doesn’t mean we can magically predict the jobs of the future or what skills workers will need to fill them. It’s not that I am opposed to efforts to try to figure out answers to those questions, or perhaps even craft some programs to try to address them (although I agree with my colleague Matt Mitchell that many past worker training programs “seem indistinguishable from corporate welfare.”) But worker retraining or reskilling usually fails because it’s like trying to centrally plan the economy of the future. It’s a fool’s errand.

In my book, I pointed out that, when you look back at past predictions regarding the job needs of the future that we now live it, those predictions were off-the-mark. The fact is, an “expert” writing in the early 1980s about the job needs of the future didn’t even have the vocabulary to describe or understand the jobs of the technological era we now live in. Here’s how I put it in my book:

It’s also worth noting how difficult it is to predict future labor market trends. In early 2015, Glassdoor, an online jobs and recruiting site, published a report on the 25 highest paying jobs in demand today. Many of the job titles identified in the report probably weren’t considered a top priority 40 years ago, and some of these job descriptions wouldn’t even have made sense to an observer from the past. For example, some those hotly demanded jobs on Glassdoor’s list include[1] software architect (#3), software development manager (#4), solutions architect (#6), analytics manager (#8), IT manager (#9), data scientist (#15), security engineer (#16), quality assurance manager (#17), computer hardware engineer (#18), database administrator (#20), UX designer (#21), and software engineer (#23).Bessen’s point is really important, and too often forgotten in discussions about reskilling for the future. When I think about the sort of skills that I picked up the early 1980 as a teenager using a clunky old Commodore 128 computer, or that my own teenage kids pick up today just by tinkering with their gadgets (computers, smartphones, gaming consoles, etc), I think about how those skills were not centrally planned for by anyone. It was mostly just learning by doing. A lot of the coding skills people use today they learned by trial and error and without taking any course to do so.

Looking back at reports from the 1970s and ’80s published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the federal agency that monitors labor market trends, one finds no mention of these computing and information technology–related professions because they had not yet been created or even envisioned.[2] So, what will the most important and well-paying jobs be 30 to 40 years from now? If history is any guide, we probably can’t even imagine many of them right now.

Of course, as with previous periods of turbulent technological change, many of today’s jobs and business models will be rendered obsolete, and workers and businesses will need to adjust to new marketplace realities. That transition takes time, but as James Bessen points out in his book Learning by Doing, for technological revolutions to take hold and have a meaningful impact on economic growth and worker conditions, large numbers of ordinary workers must acquire new knowledge and skills. But “that is a slow and difficult process, and history suggests that it often requires social changes supported by accommodating institutions and culture.”[3] Luckily, however, history also suggests that, time and time again, society has adjusted to technological change and the standard of living for workers and average citizens alike improve at the same time.

In his book, Bessen uses the example of bank tellers to illustrate how convention wisdom about future trends is often wildly off the mark. With the rise of ATMs a few decades ago, many thought the days of bank tellers were numbered. But Bessen’s research shows that we have more bank tellers today than we did 40 years ago because once the ATMs could handle the menial tasks of counting and distributing money, the tellers were freed up to do other things.

I’m not saying we can just leave the future of workers to chance and hope everyone can learn on the fly like that. Some government programs will be needed, and many could even help. But let’s not kid ourselves into thinking that we somehow have a crystal ball that we can stare into and, like a technological Nostradamus, somehow divine the jobs and skills of a radically uncertain future.

Our better hope lies in creating an innovation culture that is open to new types of ideas, jobs, and entrepreneurialism. We might better serve the workers of the future by ensuring that they are not encumbered by mountains of accumulated red tape in the form of archaic rules, licenses, permitting schemes, and other obstacles to progress. My colleague Michael Farren also testified last year and offered some concrete near-term reform proposals to help bridge the skills gap by “revis[ing] the federal tax code to allow tax deductions for all forms of productivity-enhancing investments, including investment in training workers to perform new jobs,” and also addressing government aid programs “that might be lowering the supply of workers, thereby contributing to the lack of skilled workers available.”"

Reynolds on the Return of Antitrust

By David Henderson.

"Cato Institute Senior Fellow Alan Reynolds is in true form in his article “The Return of Antitrust?” in Regulation, Spring 2018. [Two disclosures: (1) In the late 1970s, Alan, more than anyone else, encouraged me to write for general-interest publications and not just for academic journals, and I still feel thankful; (2) I’m one of the regular contributors to Regulation, one of my favorite magazines.]

Some highlights follow:

Antitrust and Consumer Welfare

In the renowned 2004 study “Does Antitrust Policy Improve Consumer Welfare? Assessing the Evidence,” Brookings Institution scholars Robert Crandall and Clifford Winston found “no evidence that antitrust policy in the areas of monopolization, collusion, and mergers has provided much benefit to consumers and, in some instances, we find evidence that it may have lowered consumer welfare.” But consumer welfare is not what drives populist/progressive Better Deal enthusiasts. Since the Chicago School shifted the emphasis of antitrust to consumer welfare, complains Pearlstein, “courts and regulators narrowed their analysis to ask whether it would hurt consumers by raising prices.” Pearlstein would like courts and regulators to pay more attention to “leveling the playing field.” [Lina] Kahn likewise argues that “undue focus on consumer welfare is misguided. It betrays legislative history, which reveals that Congress passed antitrust laws to promote a host of political economic ends.”Recent Mergers?

Kahn claimed the Chicago School’s “consumer welfare frame has led to higher prices and few efficiencies,” citing a collection of studies John Kwoka discusses in his 2014 book Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies. [Brookings Institution political scientist William] Galston and [his assistant Clara] Hendrickson praise the book as “a comprehensive study of recent mergers.” In reality, 10 of the book’s 42 “recent” mergers happened between 1976 and 1987, and 21 others happened in the 1990s. Those old studies were mainly focused on very few industries, including airline and railroad mergers enforced by the Department of Transportation and the Surface Transportation Board, rather than the Justice Department or Federal Trade Commission. Senator Schumer as well as Galston and Hendrikson allude to “recent” airline fares as a reason for tougher antitrust, even though five of the seven airline mergers in Kwoka’s book occurred in 1986–1987, and the other two in 1994.New Competition that Pearlstein ignores

Pearlstein notes that Kwoka’s list of higher prices blamed on mergers includes “hotels, car rentals, cable television, and eyeglasses.” The goods on that list look as old-fashioned as Kwoka’s definition of “professional journal publishing” as involving print only, ignoring electronic publications. Hotels now face stiff competition from Airbnb; rentals cars from Uber; cable companies face “cord-cutting” alternatives such as broadcast HDTV, satellite providers DirecTV and Dish, and internet providers such as Roku, Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, and more. The claim that eyeglass maker Luxottica controls 80% of U.S. optician chain sales ignores the sales made by thousands of independent optometry practices, huge retailers Walmart and Costco, and online retailers Zenni Optical and Warby Parker. It is difficult to imagine how Pearlstein or Kwoka could seriously suggest consumers face monopoly pricing from such industry leaders as Southwest Airlines, Marriott hotels, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, or Costco Optical.Jason Furman’s Mistake

A widely quoted 2016 Issue Brief from President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) includes a graph from then-chairman Jason Furman showing large recent gains in “returns on invested capital” among public non financial firms as calculated by the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. The Furman CEA claimed that this demonstrates a surge in “rents,” which was wrongly defined as returns “in excess of historical standards.” At McKinsey, however, Mikel Dodd and Werner Rehm explained that returns appear to be growing larger by their measure because invested capital as traditionally measured (plant and equipment) became smaller as the economy shifted from capital-intensive manufacturing to services and software.Are There Only 13 Industries?

Pearlstein wrote, “There is little debate that this cramped [Chicago School] view of antitrust law has resulted in an economy where two-thirds of all industries are more concentrated than they were 20 years ago, according to a study by President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, and many are dominated by three or four firms.”The whole piece is well worth reading."

That is not what the 2016 CEA Brief said. What it said was the largest 50 firms (not “three or four”) in 10 out of 13 “industries” (really sectors) had a larger share of sales in 2012 than in 1997. Pearlstein’s “two-thirds of all” means 10 out of 13, but the United States has more than 13 industries. In pointlessly broad sectors such as retailing, real estate, and finance, the top 50 firms had a slightly larger share of sales in 2012 than in 1997. The 50 largest in “retailing” accounted for 36.9% of sales in 2012, said the CEA, but that combines McDonald’s, Kroeger, Home Depot, and AT&T Wireless as if they were colluding competitors.

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Less regulation has led to increased broadband investment

See Broadband CapEx Investment Looking Up in 2017 by Jonathan Spalter of USTelecom. Excerpts:

"As pro-consumer policy incentives for broadband innovation and investment continue to take root, the two-year decline in private capital investment in U.S. broadband infrastructure from 2014 to 2016 appears to be in the rearview mirror, according to a preliminary USTelecom analysis of the 2017 capital expenditures of wireline, wireless, and cable broadband service providers*.U.S. broadband companies, excluding independent competitive local providers and fiber operators**, have invested between $72 and $74 billion in network infrastructure in 2017, compared to $70.6 billion in 2016, showing at least an increase of nearly $1.5 billion.

Many factors affect these figures—from the overall health of the economy to intense and rising competition, not only among broadband providers but across the internet with the ongoing convergence of entertainment, media and communications.

But as someone who closely watches and works with the companies that are among the leading investors in our nation’s economy, it is essential that we give substantial credit where it is clearly due—restoring U.S. innovation policy to the constructive, nimble and pro-consumer framework that has guided the meteoric rise of our economy since the early days of the internet.

It is no coincidence that the broadband capex slow down coincided with the previous FCC—in its final two years—abruptly shifting course down a sharply more regulatory path headlined by the controversial attempt to subject consumer broadband services to heavy, archaic regulations written nearly a century ago."

Labels:

Infrastructure,

Net neutrality,

Regulation,

Telecommunications

Does Everyone Have Two Jobs?

By Andy Puzder in The WSJ. Excerpts:

"But Bureau of Labor Statistics data show only a small minority of Americans work multiple jobs. That percentage has been around 5% of working Americans since 2010, though it was higher before then. Last month 7.6 million, or 4.9%, of the 155.5 million working Americans had multiple jobs.

Are people working “60, 70, 80 hours a week”? Rarely. But for a brief dip during the recession, private-sector employees have worked an average of 34.2 to 34.6 hours a week since BLS began tracking the data in 2006. The average stood at 34.5 hours in June.

BLS considers 35 hours a week “full time,” so working 70 or 80 hours would be equivalent to two full-time jobs. Only 360,000 people worked two full time jobs in June—0.2% of the workforce. There may well be people working 60 hours a week or more on one job—but if that were common, the overall average for hours worked would be well above 34.5."

"In June, wages increased 3.8% year over year for retail-sector employees. It was their highest percentage increase since 2001 using June as the base year. Wages in the hospitality-and-leisure sector, including restaurants, rose 3.3% year over year—on top of a 4.3% increase in 2017. In a fast-growing economy, the demand for labor increases, and more employers have to pay above the applicable minimum wages to get employees."

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Not properly accounting for marketing and management costs means we’ll mistakenly classify payments to workers as excess profits

See What Current Research (Still) Gets Wrong about Market Power by James Traina at ProMarket (The blog of the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business). Excerpts:

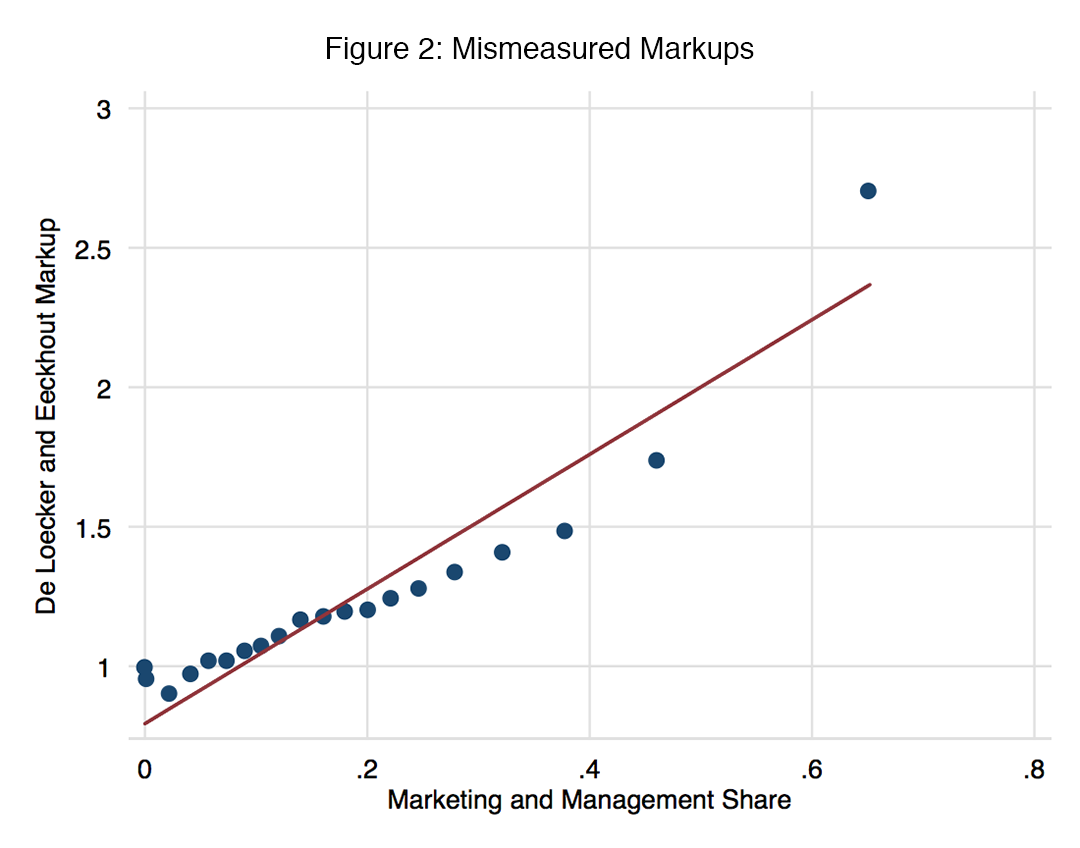

"recent studies err in the same way as De Loecker and Eeckhout’s earlier work by not properly accounting for marketing and management costs. Marketers and managers are skilled labor, so if we omit them from our calculations, we’ll mistakenly classify payments to workers as excess profits. The De Loecker and Eeckhout method does precisely this by excluding these costs entirely in estimating market power.

As I document in my own work on US firms, a direct artifact of this omission is a large markup. Figure 2 plots the correlation between markup estimates using this method, and the share of expenses contributed by marketing and management. The strong correlation shows that where these authors would infer significant market power is exactly where we see a greater contribution from these costs.

Moreover, these costs are a rising share of expenses for US public firms, so excluding them makes the problem worse and worse over time. I find that including them in market power measurement substantially flattens any trend in US markups; instead of skyrocketing, market power has remained relatively stable for the last 70 years, and is about as high today as in the 1950s.

The rise of marketing and management suggests that the middle-class squeeze is an outcome of changes in technology. Labor economists have collected a wealth of evidence consistent with this hypothesis (see here for a review). It also squares with the rise in profits: technological change that increases returns to scale would also increase profit rates, since costs would be lower for all the units up to the marginal unit. Firms are shifting the way they produce, and only workers who can keep pace end up benefiting.

If marketing and management are also a rising share of expenses for non-US firms, then the markup estimates of these global market power papers will understate costs increasingly over time, and thus overstate markups increasingly over time. De Loecker and Eeckhout (2018) do not address this point. Diez, Leigh, and Tambunlertchai (2018) make an attempt, but they do so in a way that can only adjust the level of markups, not the trend."

"Other prominent work hypothesizes that the rise in US industrial concentration is a consequence of weakened US antitrust enforcement. If market power is increasing even in Europe, where antitrust enforcement has remained relatively unchanged, then we would need drastic competition policy reform to affect curb existing market power. However, if market power is stable, then we need to look elsewhere for culprits of stagnant wages and rising concentration, such as how trade and technology impact markets."

"Ultimately, since sales and expenses are observable, the technical debate centers on what’s the right measure of flexible inputs, and how we estimate its elasticity. Specifically, do we include market and management costs as part of flexible inputs? And how should we account for them otherwise?

"My proposed solution is to answer yes to this first question: treat marketing and management costs as part of flexible inputs. A flexible input is one that firms can change to affect output without big adjustment costs. The simple economics argument here is that hiring skilled marketers or managers increases sales, and it’s pretty easy to do that within a year’s time. If you accept these premises, then you should mark these costs as flexible.

If you’re still skeptical, my paper supports these premises with two reassuring pieces of empirical evidence. First, markup estimates including marketing and management costs aren’t sensitive to the choice of shorter or longer production horizons. Even if these costs weren’t already flexible in the short-run, they would be flexible in the long-run. Second, the expenses change smoothly within a firm. If these costs weren’t flexible, firms would change them in bursts. Overall, my proposed solution produces a much flatter trend in US data, and may affect global estimates similarly."

"As a final note for perspective, Simcha Barkai, one of the first academics to sound the market power alarm, makes this excellent point in his recent work with Seth Benzell:

The profits implied by De Loecker and Eeckhout (2017) exceed 80% of gross value added in 2014. These implied profits are implausibly high: so long as capital costs are non-negative, profits can’t exceed gross value added less compensation of employees. This bound implies that profits can’t exceed 42% of gross value added.If the De Loecker and Eeckhout markups were representative of the overall US economy, Barkai’s back-of-the-envelope implies that 80 percent of GDP is going to economic rents, which leaves 20 percent for labor and capital. But labor alone is measured at over 40 percent. Of course, these estimates still rely on extrapolating public firms estimates to the overall economy. In my paper, I show that inference from public firm markups significantly overstates aggregate market power estimates, stressing that it’s important for future research to apply similar methods to administrative production datasets that include private firms."

Is Portugal an anti-austerity story?

By Tyler Cowen.

"A recent NYT story by Liz Alderman says yes, but I find the argument hard to swallow. Here’s from the OECD:

The cyclically adjusted deficit has decreased considerably, moving from 8.7% of potential GDP to 1.9% in 2013 and to 0.9% in 2014. This is better (lower) than the OECD average in 2014 (3.1%), reflecting some improvement in the underlying fiscal position of Portugal.Or see p.20 here (pdf), which shows a rapidly diminishing Portuguese cyclically adjusted deficit since 2010. Now I am myself skeptical of cyclically adjusted deficit measures, because they beg the question as to which changes are cyclical vs. structural. You might instead try the EC:

…the lower-than-expected headline deficit in 2016 was mainly due to containment of current expenditure (0.8 % of GDP), particularly for intermediate consumption, and underexecution of capital expenditure (0.4% of GDP) which more than compensated a revenue shortfall of 1.0% of GDP (0.3% of GDP in tax revenue and 0.7% of GDP in non-tax revenue)Does that sound like spending your way out of a recession? Too right wing a source for you? Catarina Principle in Jacobin wrote:

…while Portugal is known for having a left-wing government, it is not meaningfully an “anti-austerity” administration. A rhetoric of limiting poverty has come to replace any call to resist the austerity policies being imposed at the European level. Portugal is thus less a test case for a new left politics than a demonstration of the limits of government action in breaking through the austerity consensus.Or consider the NYT article itself:

The government raised public sector salaries, the minimum wage and pensions and even restored the amount of vacation days to prebailout levels over objections from creditors like Germany and the International Monetary Fund. Incentives to stimulate business included development subsidies, tax credits and funding for small and midsize companies. Mr. Costa made up for the givebacks with cuts in infrastructure and other spending, whittling the annual budget deficit to less than 1 percent of its gross domestic product, compared with 4.4 percent when he took office. The government is on track to achieve a surplus by 2020, a year ahead of schedule, ending a quarter-century of deficits.This passage also did not completely sway me:

“The actual stimulus spending was very small,” said João Borges de Assunção, a professor at the Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics. “But the country’s mind-set became completely different, and from an economic perspective, that’s more impactful than the actual change in policy.”Does that merit the headline “Portugal Dared to Cast Aside Austerity”? Or the tweets I have been seeing in my feed, none of which by the way are calling for better numbers in this article?

I would say that further argumentation needs to be made. Do note that much of the article is very good, claiming that positive real shocks help bring recessions to an end. For instance, Portuguese exports and tourism have boomed, as noted, and they use drones to spray their crops, boosting yields. That said, it is not just the headline that is at fault, as the article a few times picks up on the anti-austerity framing."

Monday, July 23, 2018

Florida’s low state tax burden boosts labor force and growth

By Nicholas Spaunburgh in The Tallahassee Democrat. Excerpt:

"Academic evidence supports these claims. For example, Florida’s decision to not levy a state income tax helps attract scientists and other high-income earners. Economists Enrico Moretti and Daniel Wilson found that each additional 1 percent increase in personal income tax led to a 1.6 percent out-migration of high-level scientists.

They also found slightly higher effects for state corporate income taxes, with a negative mobility response of 2.3 percent. Moretti and Wilson concluded that other highly-skilled workers likely have similar sensitivity to state taxes. Not surprisingly, FSU economist Randall G. Holcombe and Donald Lacombe found that states that raised their income tax rates more than neighboring states experienced a 3.4 percent reduction in per capita income from 1960 to 1990.

The effects are not just on population migration. A meta-analysis of 84 econometric studies by Timothy Bartik at the W.E. Upjohn Institute found taxes have a significant and sizeable effect on business activity. J. William Harden and William Hoyt, writing in the National Tax Journal, believe a consensus has emerged within the economics profession that state and local taxes negatively affect state employment levels, which in turn reduces a state’s attractiveness."

CO2 was a long-term consequence of the climate-biological system, being decoupled or even showing inverse trends with temperature

See CO2 and temperature decoupling at the million-year scale during the Cretaceous Greenhouse by in Nature Abel Barral, Bernard Gomez, François Fourel, Véronique Daviero-Gomez & Christophe Lécuyer. Here is the abstract:

"CO2 is considered the main greenhouse gas involved in the current global warming and the primary driver of temperature throughout Earth’s history. However, the soundness of this relationship across time scales and during different climate states of the Earth remains uncertain. Here we explore how CO2 and temperature are related in the framework of a Greenhouse climate state of the Earth. We reconstruct the long-term evolution of atmospheric CO2 concentration (pCO2) throughout the Cretaceous from the carbon isotope compositions of the fossil conifer Frenelopsis. We show that pCO2 was in the range of ca. 150–650 ppm during the Barremian–Santonian interval, far less than what is usually considered for the mid Cretaceous. Comparison with available temperature records suggest that although CO2 may have been a main driver of temperature and primary production at kyr or smaller scales, it was a long-term consequence of the climate-biological system, being decoupled or even showing inverse trends with temperature, at Myr scales. Our analysis indicates that the relationship between CO2 and temperature is time scale-dependent at least during Greenhouse climate states of the Earth and that primary productivity is a key factor to consider in both past and future analyses of the climate system."

Sunday, July 22, 2018

Thank Drug Warriors for the Escalating Death Toll From Superpotent Synthetic Opioids

New data show the share of opioid-related fatalities involving fentanyl analogs is rising

By Jacob Sullum of Reason. Excerpt:

By Jacob Sullum of Reason. Excerpt:

"Highly potent fentanyl analogs are playing an increasingly prominent role in opioid-related deaths, accounting for one in five such fatalities during the year ending in June 2017, according to a new CDC analysis of data from 10 states. During that period, the CDC counted 11,045 "opioid overdose deaths" in those states, including 2,275 cases where fentanyl analogs were detected. The number and proportion of deaths involving fentanyl analogs "nearly doubled" between the second half of 2016 and the first half of 2017. This trend is yet another illustration of prohibition's effectiveness, assuming the goal is to make drugs as deadly as possible.

Most opioid-related deaths now involve illicitly produced fentanyl. In the 10 states tracked by the CDC (Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin), fentanyl was detected in 57 percent of opioid-related fatalities from July 2016 through June 2017. Fentanyl analogs showed up 21 percent of the time. The most commonly detected analog was carfentanil, followed by furanylfentanyl. Ohio alone accounted for 90 percent of the 1,236 carfentanil deaths in the 10 states during this period. The other analogs detected were 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl.

The CDC notes that "carfentanil, the most potent fentanyl analog detected in the United States, is intended for sedation of large animals and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine." By comparison, the National Institute on Drug Abuse says fentanyl is 50 to 100 times as potent as morphine, while heroin is said to be about twice as potent as morphine. Prescription conversion tables indicate that hydrocodone (the opioid in Vicodin) is about as strong as morphine, while oxycodone (Percocet) is a bit stronger.

In other words, the crackdown on prescription analgesics is pushing opioid users toward increasingly potent substitutes: heroin (roughly twice as potent as morphine), which is often mixed with or replaced by fentanyl (50 to 100 times as potent) and fentanyl analogs (as much as 10,000 times as potent). Worse, the purity and potency of black-market drugs are highly variable and unpredictable, making consumers vulnerable to lethal dose miscalculation, especially when they are taking more than one substance at a time (as is typically the case in drug-related deaths). The wider the range of purity and potency, the greater the potential for fatal mistakes.

Prohibition contributes to this problem in several ways. It creates a black market where consumers don't know what they're getting, encourages dilution along the supply chain that dealers may try to counteract by adding fentanyl or fentanyl analogs to heroin, and pushes traffickers toward more potent drugs, which reduce the volume that must be smuggled for any given number of doses. Increased enforcement of prohibition magnifies these tendencies, exposing users to greater risks and feeding the upward trend in opioid-related deaths."

Why Be Libertarian?

From Cafe Hayek.

"from page 3 of Tom Palmer’s 2013 essay “Why Be Libertarian?, which is chapter 1 of Why Liberty, an excellent 2013 collection edited by Tom:

As you go through life, chances are almost 100 percent that you act like a libertarian. You might ask what it means to “act like a libertarian.” It’s not that complicated. You don’t hit other people when their behavior displeases you. You don’t take their stuff. You don’t lie to them to trick them into letting you take their stuff, or defraud them, or knowingly give them directions that cause them to drive off of a bridge. You’re just not that kind of a person.DBx: Indeed so. And the libertarian correctly understands that an act that is morally unacceptable when performed by an individual doesn’t become morally acceptable merely because individuals as a group possess the physical power to perform that act without their suffering much risk of resistance or retaliation. The burden of proof of justifying coercive actions against peaceful others is on those who people proposes such coercive actions, and this burden is a heavy one. The burden is not met simply by counting heads or hands and discovering that a majority endorses the coercive actions."

You respect other people. You respect their rights. You might sometimes feel like smacking someone in the face for saying something really offensive, but your better judgment prevails and you walk away, or answer words with words. You’re a civilized person.

Congratulations. You’ve internalized the basic principles of libertarianism. You live your life and exercise your own freedom with respect for the freedom and rights of others. You behave like a libertarian.

Saturday, July 21, 2018

Europe’s idiotic war on Google

By James Pethokoukis of AEI.

"The core of the EU’s complaint this time around is that Google used restrictions on the use of Android — which runs more than 80 percent of the world’s smartphones — to unfairly favor its own search, browser, and other services. A mobile phone company that wants to offer the Google Play app store must also preload a suite of other Google applications. In addition, it must make Google search the default search application. These and other “illegal practices,” according to EU antitrust boss Margrethe Vestager, “denied rivals the chance to innovate and compete on the merits.”

To accept the EU’s case, however, one has to ignore the reality of the modern internet, where users easily and frequently download millions of apps some 100 billion times a year. Indeed, even though developers must preload Search, Chrome, and some other Google services as a condition of licensing the app store, the arrangement is not exclusive. A device maker could also preload rival app stores and other apps. As it is, the Firefox browser, for instance, has been downloaded more than 100 million times on Play. And consider this: One thing that really bugged the EU was that the Android home screen displayed a Google Play icon and a folder of 10 other Google apps vs. the myriad of preloaded apps on the Apple home screen.

Such preloading has long been a part of Google’s phone business. It’s one thing that allows Google-developed Android to remain free, which has subsequently drastically lowered the cost and availability of smartphones. This has increased the number of people who own them. Developers in Europe and elsewhere are thus able to distribute their apps to over a billion people around the world. If Google couldn’t preload its money-making apps onto Android phones, it probably wouldn’t give Android away for free.

Another reality: Google has a powerful app store competitor — Apple, which rakes in a whopping 87 percent of smartphone profits.

But maybe this isn’t just about competition. Amazon, Apple, and Facebook have also been the target of legal or regulatory actions lately, after all.

Yet you won’t find the U.S. suing Europe’s super-successful platform companies because, well, there aren’t any. Likewise, Europe has generated only a tenth of the fast-growing tech startups, or unicorns, found in the U.S. Instead of company creation, Europe seems to be specializing in regulation and investigation. The whole thing stinks of platform envy."

In UK, government predictions of the savings smart meters will generate for consumers are inflated, out of date and based on a number of questionable assumptions

See Smart meters to save UK households only £11 a year, report finds: Report by MPs and peers says predicted benefits of scheme ‘likely to be slashed further’ by The Guardian. Excerpts:

"the rollout of smart meters risked going over budget, was past its deadline and must be reviewed immediately.

The £11bn scheme to put 53m devices in 30m homes and small businesses by 2020 has been “plagued by repeated delays and cost increases”"

"high numbers of the devices had gone “dumb” after installation because of problems caused by switching provider or mobile data coverage."

"suppliers were almost certain to miss the 2020 rollout deadline and that its benefits were “likely to be slashed even further”."

"the entire programme has been funded by customers through higher energy bills"

"they are not presently guaranteed to see the majority of the savings that do materialise,”"

"2016 paper by the BEIS that said the expected saving on an annual dual fuel bill in 2020 had more than halved, from £26 to £11.14.

Costs are increasing meanwhile, with spending on installation £1bn more than planned, threatening to eventually outstrip the £16.7bn gross benefit the project was supposed to deliver."

"The suppliers have fallen behind schedule, however, with just over 11m smart meters reportedly operational as of March 2018. That leaves three years to fit more than 40m by the 2020 deadline"

"suppliers were still rolling out obsolete first generation meters, which were supposed to have been succeeded by November 2016.

"more than half of the smart meters, about 500,000 a year, had gone “dumb”"

Friday, July 20, 2018

Early Childhood Education Fails Another Randomized Trial

From Tim Taylor. Excerpt:

"But there are now two major randomized control trial studies looking at the the results of publicly provided pre-K programs, and neither one finds lasting success. Mark W. Lipsey, Dale C. Farran, and Kelley Durkin report the results of the most recent study in "Effects of the Tennessee Prekindergarten Program on children’s achievement and behavior through third grade" (Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2018, online version April 21, 2018).