"Here’s a letter to the Wall Street Journal.

Editor:

Mark Duffy asserts that America has been harmed by Canadian aluminum subsidies – a harm that allegedly justifies higher U.S. tariffs on aluminum (Letters, July 28). But although as common as pigeons in Central Park, arguments that foreign subsidies justify domestic protection crumble upon inspection.

It’s true that subsidized imports reduce outputs and employment in the U.S. industries that compete with these imports, but this effect helps, not hurts, the U.S. economy. Capital, workers, and resources released from these domestic industries become available to increase the production and employment of other domestic industries. America gets more output and jobs from these expanded industries, while foreigners pick up part of our bill for the consumption of the subsidized imports.

Given the Trump administration’s determination to “Put America First!,” it should – instead of ungratefully taxing Americans’ receipt of these Canadian gifts – send notes to our northern neighbors thanking them for joining in Mr. Trump’s effort to Make America Great Again.

Sincerely,

Donald J. Boudreaux

Professor of Economics

and

Martha and Nelson Getchell Chair for the Study of Free Market Capitalism at the Mercatus Center

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA 22030"

Thursday, July 31, 2025

Canadian aluminum subsidies allow us to increase production in other domestic industries while foreigners pick up part of our bill for its consumption

China Shocked? Hard Hit Metropolitan Statistical Areas Have Performed Well Economically Since 2000

"Much has been made of the “China Shock,” or the impact on US manufacturing from two related trade policy changes: the US granting China permanent normal trade relations in 2000, and China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. As Scott Lincicome has pointed out, the policy discussion has strayed from the academic research on this topic in several important ways: the job losses are frequently overstated, it didn’t devastate the US economy (it probably helped), and the prominent authors of papers on the China Shock don’t think the negative impacts justify broad-based tariffs.

Today I’ll deflate another piece of the China Shock political narrative: that it crushed American communities.

David Autor and co-authors have been some of the primary contributors to academic research on the China Shock, showing its negative impact on certain people living in various parts of the US and contextualizing those impacts. In a 2021 paper, those authors provide a list of the “most trade-impacted” commuting zones from the China Shock (the list is found in the Online Appendix Table A4). From this list, we can identify 10 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that are the most affected by Chinese imports (MSAs and commuting zones are defined slightly differently, but there is a lot more data available for MSAs). The remainder of the trade-affected commuting zones they identify are much smaller, rural counties, with less available data, so I won’t dig into them in this post.

What happened to those “most affected” MSAs? Here’s a shocking fact: all of the MSAs hit hard by the China Shock still managed to have significant and positive real wage growth across the distribution since 2001, the earliest comparable data in the BLS OEWS data, conveniently timed at the beginning of the China Shock (note: for Cleveland, TN the data is first available in 2005, since it was not recognized as an MSA until 2003). Wage gains in several of these places, in fact, are better than the national trends.

The chart below shows the 10th percentile and median wages, adjusted for inflation, from the BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, and BLS also publishes wages at the 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles (the 10th percentile wage is the point in the distribution where 10 percent of workers are below that wage, while the median is the middle of the distribution). Every single MSA in this group had positive real wage growth since 2001 in every single slice of the distribution that BLS reports. It is also notable that the 10th percentile workers saw larger gains than the median worker. I only show the 10th percentile wage and median wage in the chart for clarity of presentation, but all of the gains would be positive if I had used the 25th, 75th, or 90th percentiles.

For comparison, the national median wage increased by 11.5 percent (adjusted for inflation) from 2001 to 2024, and the 10th percentile wage increased by 30.1 percent. This means that most of these MSAs experienced slower wages at the bottom end than did the nation as a whole. That may be the China Shock. But we shouldn’t confuse this outcome with the communities being worse off than they were decades ago.

Perhaps wages are rising because people are dropping out of the labor force, thus artificially boosting the wages we observe in the OEWS data. That could be the case if the workers losing their jobs have below-average wages. When we look only at manufacturing jobs, all ten of these MSAs saw manufacturing employment fall since 2000, even though some of them saw recovery after the Great Recession. However, as we will see below, gains in jobs in other sectors offset those manufacturing job losses in almost all of these cities.

For comparison, total US manufacturing employment declined by 25.8 percent from 2000 to 2024. Thus, six of these ten trade-affected MSAs saw smaller declines in manufacturing employment than the nation as a whole, even though three of these MSAs (Lynchburg, San Jose, and Hickory) lost around half of the manufacturing jobs they had in 2000.

But we don’t only care about manufacturing jobs. Indeed, there isn’t necessarily a reason to prefer manufacturing jobs to other jobs. What we care about are whether people have jobs, whether those jobs pay well, and other characteristics about the jobs (how dangerous they are, how stable they are, etc.). Thus, it makes sense to look at total employment for these MSAs and not just bemoan the decline of one sector.

For comparison, total US growth in nonfarm jobs over the same period was 19.7 percent from 2000 to 2024. Thus, while the majority of these areas had total job growth below the national average, four of the MSAs had job growth that exceeded the national average. Only one MSA—Hickory, NC—clearly lost jobs since 2000, while Sioux City and Lynchburg had close to no net job growth. Thus, we can see that, at least on net, the rise in real wages for most of these hard-hit MSAs is not caused by a decline in labor force participation, though there may have been a change in exactly who the workers were and their education and training levels.

Even the one exception of Hickory, NC (full name: Hickory-Lenoir-Morgantown MSA), the worst performer in job growth in this group, has performed better than the pessimistic projections. For example, a 2011 report predicted that in Hickory, “unemployment levels won’t reach pre-recession levels for another decade,” when the unemployment rate in Hickory was 12 percent, and put the prospects for Hickory “near the bottom of the road for recovery nationwide.” But three years later, the unemployment rate was down to 6.2 percent, on par with 2006 and 2007. By 2018, it had dropped all the way to 3.7 percent, the lowest since the late 1990s, and slightly below the national rate of 3.9 percent. As my colleague (and North Carolina resident) Scott Lincicome has repeatedly noted, Hickory’s economy is doing well today, and the area has repeatedly been voted one of the best places to live in the country.

How did these areas perform so well, given the pessimistic narrative of the China Shock? Remember, again, to emphasize, these are the MSAs that are likely the worst hit by the Shock. We are already making the hard case, not cherry-picking MSAs with good stories of recovery.

For MSAs such as San Jose (which includes Silicon Valley), Austin, and Raleigh, their resilience from the China Shock is not surprising. As Autor et al. point out, diverse areas with a high concentration of college-educated workers in 2000 (these areas were all over 30 percent college educated, while the other “most impacted” areas were under 20 percent) and low concentration of manufacturing employment in 2000 (these areas were all under 21 percent, the lowest 3 on the “most impacted” list) were able to adapt well to the China Shock, even if they experienced significant manufacturing job losses. On the other hand, areas with the opposite combination—high manufacturing employment and low numbers of college-educated workers —faced bigger challenges in adjusting to the Shock.

Indeed, Autor and his co-authors contrast the performance of Raleigh-Cary and Hickory (separated into the commuting zones of North and West Hickory), both located in North Carolina and separated by less than 200 miles. Given their very different mixes of employment in 2000—Raleigh with just 17 percent in manufacturing and Hickory over 40 percent—we would expect Raleigh to adjust better to the Shock of increased trade penetration. And as we saw in Chart 3 above, this was the case.

As Adam Ozimek has recently pointed out, the resiliency of highly educated cities and commuting zones likely isn’t a coincidence or a mere correlation. It’s much more likely that it is a causal relationship, and there are good reasons a more-educated city would be better able to adapt to heavy exposure to the China Shock. So if there are policy implications to economically homogenous, lower-educated cities being less resilient in the face of an economic shock, it is that education and economic diversification would help, not trade barriers.

But there are other success cases we can identify that did not have Raleigh and Austin’s favorable starting position. Even San Jose, despite benefitting from the booming Silicon Valley, was a mediocre performer in employment growth, even though it performed well in wage growth (note: the wage figures are adjusted using national price indices, even though costs may have increased faster there).

One such success case is in Jonesboro, Arkansas. Employment grew faster than the national average, and wage growth also compared favorably. While Jonesboro is home to a mid-sized research university (Arkansas State University), it didn’t have a very high proportion of its population with college degrees in 2000: just 14.6 percent, less than half of the proportion in places like San Jose and Austin. Nonetheless, despite a 13 percent drop in goods-producing jobs in Jonesboro from 2000 to 2024, service-producing jobs grew by 55 percent. And this is not merely a “small base” effect, as service-sector employment was almost three times as large as goods-producing employment in 2000 in Jonesboro.

Jonesboro is no exception. Service sector employment grew in all 10 of these MSAs from 2000 to 2024, by as much as 116 percent in Austin, down to 14 and 15 percent in Lynchburg and Fort Wayne.

These outcomes reveal an important fact: contrary to the conventional political wisdom, most service-sector jobs are not bad, low-paying jobs. According to the latest BLS wage data, private-sector service jobs pay on average about $36 per hour, slightly higher than manufacturing at about $35 per hour. These are not large differences. But it is simply not the case that, on average, manufacturing jobs are better paying. And, in fact, many manufacturing jobs pay well below the wages in comparable blue-collar service industries.

Thus, once again, the lesson of the China Shock isn’t that we need more tariffs and industrial subsidies. Instead, it’s that the way to help Americans and US regions that are hurt by foreign trade (or any other economic shock) is to allow them to transition to a different, more modern industrial structure and allow their service sectors to flourish. As Lincicome and others have shown, numerous government policies thwart this necessary adjustment and thus make our workers and localities less resilient to shocks. Reforming these policies—not protectionism—should be the priority. Recovery from a large trade shock takes time, as David Autor and other economists explained recently, but that doesn’t mean recovery doesn’t happen.

To emphasize one more time, in this post I have focused on the MSAs that were most affected by the China Shock—in other words, the worst-case scenarios. Yet even these worst cases show that the US economy is more than able to adapt to employment changes brought on by international trade, even as we enjoy all of its other benefits."

Wednesday, July 30, 2025

Tuesday, July 29, 2025

California’s Bullet Train Is a Model of Progressive Governance

Trump gave Newsom a perfect opportunity to cut his losses and shift blame. Why didn’t he take it?

By Allysia Finley. Excerpts:

"At the current construction rate, the 500-mile choo choo between San Francisco and Orange County won’t be completed in the governor’s lifetime. The state as of last month hadn’t begun to lay tracks on the first 119-mile segment between Madera (pop: 68,079) and Shafter (pop: 21,915).

This first leg should have been relatively easy since the state’s rural Central Valley is lightly developed and populated. No need to raze strip malls and housing developments. A private company built a 235-mile high-speed train from Orlando to Miami in 11 years for about $6 billion. Yet it has taken California more than a decade merely to bulldoze permitting barriers and clear lawsuits."

"China has borrowed some $1 trillion to build nearly 30,000 miles of high-speed rail lines, many of which connect lightly populated towns and carry few passengers."

"Democrats claimed the train would cost a mere $33 billion and be complete by 2020. The 500-mile train trip from San Francisco to Anaheim would supposedly take only 2½ hours and cost less than flying."

"The state high-speed rail authority at the time projected 65.5 million annual riders by 2030, about five times as many passengers who take Amtrak’s trains in the more densely and heavily populated Northeast Corridor."

"But the rail authority is at least $7 billion short of what it needs to complete the first segment and needs more than $90 billion to build all 500 miles."

"healthcare for undocumented immigrants (estimated to cost $12 billion this year)."

"Democrats spent $24 billion to combat homelessness, yet the result was more homelessness. State K-12 spending has risen by 50% since 2018, but student test scores have fallen. Electric rates have surged yet power has become less reliable."

The Price of Winning the Trade War

The Japan deal is a relief, but only because the alternative is worse.

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"That $550 billion in new Japanese investment also sounds better than it may be once we know the details. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba suggested Tokyo will offer government loans and guarantees to support these “investments,” with the aim “to build resilient supply chains in key sectors.”

This raises the prospect that this money, if it arrives, will be tied up in Japanese industrial policy. And American industrial policy, since Mr. Trump said Japan will make these investments “at my direction” and the U.S. “will receive 90% of the Profits.” Yikes.

By the way, more investment inflows by definition mean a larger trade deficit in the U.S. balance of payments. Has someone told the President about this?"

"Yet the 15% rate still marks a substantial increase over the 2.5% tariff that applied to passenger cars before Mr. Trump took office."

"Mr. Trump is showing the world that the U.S. can change access to its market on presidential whim. Countries will diversify their trading relationships accordingly, as they already are in new bilateral and multilateral deals that exclude the U.S. China will expand its commercial influence at the expense of the U.S."

"It retaliated against Mr. Trump’s 145% tariffs with export restraints on vital minerals, and Mr. Trump agreed to a truce."

"the average U.S. tariff rate may settle close to 15% from 2.4% in January."

The AI Market Debate Is Old

Oskar Lange’s utopian—or dystopian—idea 80 years ago was to have a computer power the economy.

"Regarding Marian L. Tupy and Peter Boettke’s op-ed “Algorithms Can’t Replace Free Markets” (July 22): Economists have already debated whether AI could replace the market some 80 years ago when they argued over the Lange model.

Polish-American economist Oskar Lange’s utopian—or dystopian—idea was to have a big, futuristic computer replace market dynamics so that an economy could be centrally planned.

The idea of using AI to run the economy instead of an organic web of individual choices is inextricably connected to a socialist model of central planning and control. As Hungarian economist János Kornai contended, such centrally-planned systems inevitably result in a “shortage economy.” And we’ve seen that, time and again.

Vladimir Zwass

Editor in Chief, Journal of Management Information Systems"

Related post:

Fuel Energy Competition to Cut High Prices

Most localities don’t open new transmission projects to competitive bidding

"Your editorial “The Real Risk to the Electric Grid” (July 21) accurately points out the problem of escalating electricity prices, but you miss a main culprit. Electricity prices are rising in part owing to the fact that most localities don’t open new transmission projects to competitive bidding.

Many states have right of first refusal laws that give an existing utility the right to prevent competitive bidding over new transmission projects. Utilities’ market power means they get high returns for every dollar they spend on transmission infrastructure and can pass the costs on to ratepayers. Perversely, the more they spend the higher the profit. An example of how this affects prices: From 2013 to 2023 transmission costs for PJM customers increased from 9.4% to 27.4% of the total wholesale price of electricity.

Competitive bidding on transmission construction can lower electricity prices by as much as 40%. If the Trump administration wants to lower energy costs, endorsing competition is a good place to start.

Paul Cicio

Chairman, Electricity Transmission Competition Coalition"

Monday, July 28, 2025

Ronald Reagan Was No Protectionist

He agreed to cap Japanese auto imports in 1981 but hated the deal and did it only as a compromise

By Phil Gramm. Excerpts:

"Mr. Cass’s argument, now a standard protectionist claim, was that because Reagan in 1981 agreed to a temporary voluntary restraint deal limiting the number of Japanese automobiles that could be imported into the U.S."

"the president hated the deal. He agreed to the compromise only to prevent lawmakers from passing more extreme protectionist legislation."

"Any hope of passing Reagan’s 1981 budget in the Democratic-controlled House would require a near-unanimous Republican vote, which at the time was incredibly rare."

"Reagan wisely defused the issue by asking the Japanese government to agree to a temporary voluntary cap on the number of Japanese automobiles that would be shipped to the U.S., and in return the automakers announced that they were satisfied with the solution."

"Reagan was the most committed free trader ever to serve as president. Even while protectionist demands grew louder, Reagan as a candidate proposed in November 1979 a free-trade agreement for North America."

"To Reagan, free trade was simply an economic extension of freedom. In his view, except in limited circumstances involving national security, government had no right to tell people that they had to buy a product so that someone else could benefit from producing it."

"Protectionists insist that America benefited from Reagan’s voluntary restraint agreement, but Reagan certainly didn’t believe that, quietly raising the auto import cap twice."

"in 1984 the cost of the trade restraint to U.S. consumers was $6 billion. Although some 45,000 automotive jobs were estimated to be saved by the voluntary restraint, those jobs came at a cost to U.S. consumers of $133,000 per job saved—more than five times the average income of an auto worker in 1984."

"Protectionists argue the restraint agreement brought foreign auto investment to America, but Volkswagen—which wasn’t under the auto agreement—built its first U.S. plant in Pennsylvania in 1978. Foreign investment in U.S. auto plants between 1981 and 1994, when the restraint agreement was in force, averaged only $671 million a year in 2017 dollars but averaged $6.6 billion between 1995 and 2008 after the voluntary restraint ended."

The Real Risk to the Electric Grid

Power shortages are coming thanks to wind and solar subsidies. Here’s how they distort energy investment

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"The Energy report projects potential power shortfalls in 2030, as 104 gigawatts of baseload power retire in the next five years. But here’s the really bad news: That shortfalls will exist even if that production is replaced, as expected, with 209 gigawatts of the mostly solar and wind generation under development.

Americans would lose power in 2030 for an average of 817.7 hours (34 days), assuming typical weather conditions. If heat waves or storms stress the grid, outages could reach 55 days. Even without plant shutdowns, Americans would lose power for 269.9 hours (11 days) amid demand growth. The power shortages would be worse in middle America, where demand is growing fastest owing to AI data centers and renewables are displacing coal and gas.

How can this be? The answer is that the Inflation Reduction Act turbo-charged subsidies for wind and solar in ways that are distorting energy investment. Because the subsidies can offset more than 50% of a project’s cost, solar and wind became more profitable to build than new baseload gas plants. The credits enable wind and solar to under-price coal and gas plants in competitive power markets"

"Coal, nuclear and gas plants are still needed to back up solar and wind, but they can’t make a profit running only some of the time. Thus many have been closing, jeopardizing grid reliability."

"Texas’s residential power prices have risen some 40% over the last seven years."

Sunday, July 27, 2025

AI Can’t Replace Free Markets

Algorithms process data from the past while economic decisions are dynamic and forward-looking

By Marian L. Tupy and Peter Boettke. Excerpts:

"Prices enable people to engage in economic calculation, which forms the basis for the rational allocation of scarce resources among alternative ends. Prices also function as decentralized feedback loops. “A price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive,” note Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok. This dual signal communicates information about relative scarcities and simultaneously encourages economic actors to adjust their plans accordingly. When lithium prices rise, producers and consumers conserve, recycle, innovate, and explore alternatives.

The belief that AI can achieve comparable results to free markets, let alone surpass them, reflects a misplaced confidence in computation and a misunderstanding of the price system. The problem for the would-be AI planners is that prices don’t exist like facts about the physical world for a computer to collect and process. They arise from competitive bidding over scarce resources and are inseparable from real market exchanges. Moreover, prices aren’t fixed inputs to be assumed in advance. They are continually being discovered and formed by entrepreneurs testing ideas about future consumer wants and resource constraints.

Economic models that treat prices as given overlook the entrepreneurial actions that create them in the first place. Ludwig von Mises made this point in 1920: Without real market exchange, central planners lack meaningful prices for capital goods. Consequently, they can’t calculate whether directing steel to railways rather than hospitals adds or destroys value.

AI can process vast amounts of data—but always from the past. Economic action, by contrast, is forward-looking. An algorithm may extrapolate trends, but it can’t anticipate innovation and changing tastes. It can’t discover what hasn’t been imagined."

"The very data planners rely on become unreliable as people adapt their behavior to avoid being captured by the system. Our research on post-socialist transitions shows that meaningful price signals only re-emerged after private exchange and budget discipline were restored. Computational power didn’t restore order—institutional reform did."

So it is interesting to see Robert Heilbroner in his essay Socialism that he says motivation was the problem:

"The effects of the “bureaucratization of economic life” are dramatically related in The Turning Point, a scathing attack on the realities of socialist economic planning by two Soviet economists, Nikolai Smelev and Vladimir Popov, that gives examples of the planning process in actual operation. In 1982, to stimulate the production of gloves from moleskins, the Soviet government raised the price it was willing to pay for moleskins from twenty to fifty kopecks per pelt. Smelev and Popov noted:

State purchases increased, and now all the distribution centers are filled with these pelts. Industry is unable to use them all, and they often rot in warehouses before they can be processed. The Ministry of Light Industry has already requested Goskomtsen [the State Committee on Prices] twice to lower prices, but “the question has not been decided” yet. This is not surprising. Its members are too busy to decide. They have no time: besides setting prices on these pelts, they have to keep track of another 24 million prices. And how can they possibly know how much to lower the price today, so they won’t have to raise it tomorrow?This story speaks volumes about the problem of a centrally planned system. The crucial missing element is not so much “information,” as Mises and Hayek argued, as it is the motivation to act on information. After all, the inventories of moleskins did tell the planners that their production was at first too low and then too high. What was missing was the willingness—better yet, the necessity—to respond to the signals of changing inventories. A capitalist firm responds to changing prices because failure to do so will cause it to lose money. A socialist ministry ignores changing inventories because bureaucrats learn that doing something is more likely to get them in trouble than doing nothing, unless doing nothing results in absolute disaster."

Meet the Medicaid Double-Dippers

The feds find that 2.8 million people are on two government health-insurance plans

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"the government has now found that up to 2.8 million Americans are enrolled in two separate health plans underwritten by taxpayers.

"1.2 million Americans last year were enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program in two or more states."

"another 1.6 million enrolled in both Medicaid and an ObamaCare plan with taxpayer subsidies in 2024."

"The Biden Administration banned states from checking Medicaid eligibility more than once a year, though many people need the program only as a temporary safety net."

"the duplicate enrollment problem is costing as much as $14 billion a year."

The Lunacy of Lawfare Against the Fed

Criminalizing a spat over interest rates is an Argentina-level mistake

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"The complaint in MAGA quarters is that the multiyear renovation of several office buildings in the Fed’s Washington, D.C., campus is running way over budget—the cost is said to total some $2.5 billion now, up from a $1.9 billion estimate when the refurbishment started.

It’s a dubious project, with a zoning application that envisioned a new underground parking garage and concourse connecting two buildings, atria and water features, a jazzed up “executive” dining facility, and luxury finishes. It’s also not the first government building project to run over budget. And if you think this cost overrun matters to the federal budget you missed a few decimal points and commas in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act."

"Now that Congress is interested in the Fed, lawmakers have plenty of better ways to spend their time. They could debate the dual mandate (price stability, plus full employment) they handed the Fed in the 1970s, or the appropriateness of the Fed’s ample-reserves regime, its delivery of forward guidance, or its practice of paying interest on banks’ reserve balances and whether Congress could or should act to curtail any of this."

Medical Schools Quietly Maintain Affirmative Action

Some still use race to make admissions decisions even though the Supreme Court said it’s illegal

By Jason L. Riley. Excerpts:

"at 22 of the [23] schools Asian and white applicants who were accepted had higher Medical College Admission Test scores than their black peers."

"at 13 of the schools, the average MCAT score of Asian and white applicants who were rejected was higher than the average MCAT score of black applicants who were accepted."

"Four historically black medical schools in the U.S. produce about half the country’s black doctors, and none of them use affirmative action to admit students. Research shows that black students who attended medical schools where everyone was admitted under the same academic requirements performed better than blacks admitted to more-prestigious schools that used affirmative action."

"race-neutrality produces more diversity than racial favoritism. Black college graduation rates were growing faster before the 1970s, the first full decade of affirmative action. “But after 1970, the relative rate at which blacks were completing college dropped, then flatlined, and never recovered its previous upward trajectory,” according to “The Upswing,” a 2020 book by Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett. “In fact, today black Americans are completing college at a lower rate compared to whites than they were in 1970.”"

"large racial preferences that steer students into schools where they are more likely to struggle are simultaneously steering them away from schools where they are more likely to thrive."

"the vast majority of schools would be as racially integrated, or more racially integrated, under a system of no preferences than under a system of large preferences.”"

Saturday, July 26, 2025

Could 2% of Elon Musk's wealth solve world hunger?

See 2025’s Counter-Tweet of the Year? by Dan Mitchell.

"I’ve already shared four contestants for the counter-tweet of the year.

- Slapping down a leftist who wanted people to think freebies are the route to political success.

- Slapping down a leftist who wanted people to think capitalism is correlated with poverty.

- Slapping down a leftist who wanted people to think China delivers more for citizens than the United States.

- Slapping down a leftist who wanted people to think socialism delivers more than capitalism.

Today, I’m going to add another contestant. Excepts I’m breaking the rules.

That’s because this counter-tweet is from 2021. But a reader sent it to me a few weeks ago and I can’t resist sharing it more widely.

You can read the CNN report by clicking here.

What makes this tweet so appealing is that it exposes the utter hypocrisy and vapidity of David Beasley, the official from the United Nations who seems to think stealing Elon Musk’s wealth would solve world hunger.

Yet the U.N.’s budget for supposedly solving world hunger was already greater than 2 percent of Musk’s wealth at the time.

So why hadn’t Mr. Beasley’s bureaucracy already ended hunger?

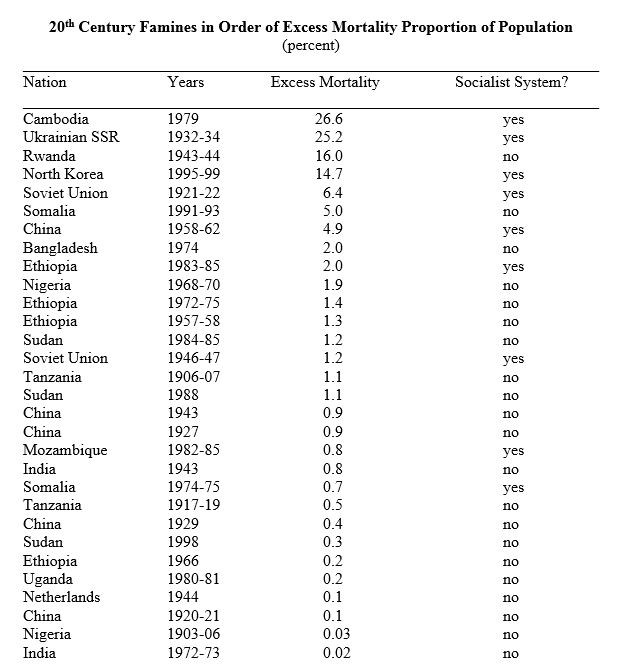

By the way, I can’t resist pointing out that governments almost always are the cause of starvation, either because of wars or catastrophic socialist policies.

Needless to say, the two CNN reporters (Eoin McSweeney and Adam Pourahmadi) did not even mention any of these points in their article.

Yet another example of statist bias in the media, with journalists basically acting at stenographers for the left.

And I suppose this is a good reminder that the United Nations is infamous for wasting money."

Big business is a myth

"Many policy discussions, from antitrust to telecom policy, focus on how large businesses should be. Almost no one asks the big questions. Why are businesses created in the first place? Wouldn’t an economy comprised of independent individuals yield greater productivity? Or would a society organized as one large corporation be more efficient? At first glance, a production process where every worker is an independent contractor might seem most efficient.

In reality, businesses range in size from corner stores to multinational corporations. Why are there differences in sizes? Some claim that certain businesses are simply greedier or more adept at growing. In his famous article “The Nature of the Firm,” economist Ronald Coase had a deeper answer: transaction costs.

Take the automobile-making process as an example. Auto companies tend to be very large. It takes thousands of engineers, designers, safety experts, and truckers to successfully design, build, and transport a single car. A decentralized body of independent contractors would have trouble managing the endless contracts, interviews, and logistics needed to coordinate the whole process. Hence, companies consolidate individuals and resources to reduce transaction costs. In other words, companies greatly reduce friction.

Transaction costs explain why businesses are formed: to decrease the producer’s total cost. High production costs make a firm uncompetitive and force higher prices, which are often incurred by the buyer. The structure a business provides helps producers to avoid this problem by consolidating capital to one location with long-term contracts and aligned goals.

But not every industry is the same. In some industries, like autos, bigger firms have the lowest transaction costs. In other industries, like corner stores or boutique crafts, smaller producers have lower transaction costs. That explains the wide variation in business sizes.

Nonetheless, transaction costs alone do not explain all growth. Many businesses have advantages of scale. As a business produces more goods, the marginal cost (the cost per producing one additional unit) often decreases. This increases the good’s average profit through lowering the average total cost of production.

In layman’s terms, the cost of producing the next unit differs at every quantity produced. Typically, this marginal cost decreases as the quantity increases. However, this process is not unlimited, due to transaction costs. Coordination problems, including layers of management, paperwork, and other frictions, increase with the size of the firm. This leads to diminishing marginal returns. A company stops production when the cost of producing additional goods exceeds the profits it generates. This self-regulating mechanism prevents endless growth. Ironically, the search for a profit is the same factor that grows and limits a business.

In short, transaction costs and diminishing marginal returns show us that companies have a natural upper limit on corporate size. If a company becomes too big and bureaucratic, a smaller and nimbler competitor with lower transaction costs can gain ground in the market. Just as FedEx’s market entry in the 1970s caused a bulky and inefficient US Postal Service to improve its service for customers, transaction costs naturally regulate the size of big companies.

Ronald Coase’s idea of natural limits on corporate size has been under attack. Economic populists on both sides of the aisle have criticized large corporations, without economic grounding, for being too big. “Big business” has become a politicized, arbitrary term used by elected officials to signal their solidarity with American consumers. The first step to overcoming populist anger is understanding that companies cannot endlessly expand, particularly due to transaction costs and diminishing returns."

Friday, July 25, 2025

Did USAID Really Save 90 Million Lives? Not Unless It Raised the Dead

A Lancet study’s inflated numbers are being used to push a partisan narrative, not inform public policy.

By Aaron Brown. He teaches statistics at New York University and at the University of California at San Diego.

""Is [the U.S. Agency for International Development] a good use of resources?" James Macinko, a health policy researcher at UCLA, asked in an NPR interview this month. "We found that the average taxpayer has contributed about 18 cents per day to USAID." That "small amount," Macinko estimated, had prevented "up to 90 million deaths around the world."

Macinko was referring to a study he coauthored, which was published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet. In addition to estimating that USAID programs had saved 90 million lives from 2001 to 2021, Macinko and his colleagues project that if the Trump administration's USAID cuts continue through 2030, an estimated 14 million people could die who otherwise would have lived.

In the same NPR story, Brooke Nichols, an infectious disease mathematical modeler and health economist at Boston University, gushed about the study. "Putting numbers to the lives that could be lost if funding isn't restored does something very important," she said. "I like [the study's] statistical approach; it was really well done and robust."

To the contrary, the study's statistical approach was poorly done and not at all robust. But you need not be an economist or a mathematician to recognize that its results are absurd. The authors failed to apply common sense to the numbers, and so did reporters at NPR, the BBC, the Associated Press, NBC, and other news outlets that amplified the study's findings.

Is it plausible that USAID programs saved more than 90 million lives from 2001 to 2021? Let's compare that to the total decline in worldwide mortality during the same period.

In 2001, the United Nations reports, there were 52.43 million deaths, or 8.4 per 1,000 people. In 2002, the death rate fell slightly; if it hadn't, 370,000 additional people would have died. In 2003, if the 2001 death rate had stayed constant, 750,000 more would have died, and so on. If you add up all the people who would have died over 21 years if the 2001 death rate had remained constant, you get 79 million lives saved.

The Lancet study claims USAID programs saved more than 90 million lives during this period. In other words, USAID was allegedly responsible for the entire global improvement in mortality, plus another 11 million lives.

If you drill down into the numbers, the claim gets even more absurd. Most of the mortality decline (47 million of the 79 million) occurred in China, which received only 73 cents per capita annually from USAID. The least developed countries—the ones with the highest per capita USAID spending—actually saw an increase in mortality of 8 million during the study period, thanks to higher average death rates from 2001 to 2021.

Even if you believe that foreign aid is the primary cause of the declining death rate, these numbers make no sense. USAID comprises about 60 percent of U.S. foreign aid, and the U.S. contributes about a third of all government aid worldwide. Private cross-border charity dwarfs the USAID budget. Was all that money wasted while USAID funds were well-spent? Did advances in medicine, agriculture, public health, and economic growth have no role?

Anyone claiming that USAID was the sole source of declining global mortality during the two decades covered by The Lancet study bears a tremendous burden of proof. Yet the study does not provide convincing evidence of any mortality reduction attributable to USAID.

Studies of this sort often involve problematic data, plagued by missing values, inaccurate numbers, and changes in definitions. Such data require complex processing. To avoid reporting risible results, researchers must do constant reality checks. If simple analysis reveals an effect, more complex methods can refine it, making the result more certain and precise. But when simple methods show no effect, as in this case, it is dangerous to rely entirely on complex methods whose results defy common sense.

The authors of the study began with a common academic approach called "regression analysis." They compared average mortality declines in countries with little or no per capita USAID spending to declines in countries with high per capita USAID spending.

Regression analysis shows only correlation, which does not demonstrate causation. Most researchers are careful to note this distinction. But Macinko et al. claimed their analysis showed USAID caused mortality declines, which is statistically impossible.

That assumption is particularly problematic in this case because a lot of USAID spending went to the same countries that also get aid from other sources. Effectively, the authors gave USAID credit for all the aid that countries received, no matter the source.

In any case, simple regression analysis did not demonstrate any correlation between per capita USAID spending and mortality declines.

For four of the 21 years in their study, Macinko et al. used "dummy variables" to ignore data showing USAID was associated with mortality increases. Their excuses for excluding two of the four years were the 2008 global economic shock and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. So why exclude the remaining two? "To adjust for major economic and health shocks," the authors say, with no clue about what those shocks were and why they were more important than shocks in other years.

It's not clear why shocks should be ignored in the first place. Does it not matter that USAID recipient countries were hit harder by COVID and the global financial crisis than other countries? Does USAID only save lives in calm times and cost lives in turbulent ones? If so, don't we care about the net lives saved or lost at all times?

Next, the researchers tested 48 "control variables." The purpose of these adjustments is to account for factors unrelated to USAID spending that affect mortality rates. Unfortunately, in this case, there are no good controls. For example, the study included education spending and the availability of piped water; however, since USAID funds education and water infrastructure, these factors are related to the amount of USAID received. All the control variables tested were things affected by USAID spending.

Including controls that are causally linked to your main variable of interest—USAID spending in this case—can cause illusory effects to appear statistically significant. This is particularly problematic when you select a large number of control variables relative to the number of data points and choose those control variables from a long list of candidates.

Macinko et al. did not preregister their controls, meaning they did not publish a research plan that committed them to a particular set. That safeguard aims to prevent researchers from falling prey to the temptation of selecting control variables based on whether the results align with their preconceptions.

What about the estimate that the Trump administration's USAID cuts, if continued, will result in 14 million preventable deaths by 2030? Programs like USAID have numerous consequences, both positive and negative, and it is impossible to accurately calculate or project their impact with any confidence. Pretending to have scientific confidence in a quantitatively dubious measure, such as lives saved, is irresponsible and leads to a loss of trust in science.

The Lancet study seems designed to generate a partisan talking point, suggesting that anyone who supports the Trump administration's actions values 18 cents over 90 million lives. Note the trick of making the cost look small by dividing it among 150 million U.S. taxpayers and 365 days per year while making the benefit look large by totaling it over the entire globe for 21 years.

This study has nothing to do with science. It waves the bloody shirt while feigning scientific detachment."

Evidence of an improving environment

See Al Gore or Julian Simon: What Is the Real State of the Environment? by Peter Jacobsen. He is an economics professor at Ottawa University. Excerpt:

"more than 90% of Americans, according to a 2021 Environmental Protection Agency publication, are served by water that fully meets EPA standards (a 20% increase from 1993, when only about 75% of U.S. drinking water met the EPA’s criteria).

Air pollution trends have moved similarly. EPA trend data shows dramatic decreases in several measurable air pollutants since 1980, including carbon monoxide (down 88%), nitrogen dioxide (down 66%), particulate matter (down 65%) and volatile organic compounds (down 61%)."

Thursday, July 24, 2025

Fifteen Years of Dodd-Frank: A Legacy of Missed Targets and Regulatory Overreach

+As we mark the 15th anniversary of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, it’s a great time to ask whether the law lived up to the hype. Admittedly, it’s rather difficult for someone who edited The Case Against Dodd-Frank to be objective, but let’s start with the law’s preamble.

Right there on page 1 (out of 850), it says that Congress enacted Dodd-Frank to:

…promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end “too big to fail,” to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes.

Well, Dodd-Frank clearly failed to end “too big to fail” or to end bailouts; the 2023 banking crisis and the government’s response took care of those. And those two items go hand in hand with “improving accountability and transparency in the financial system,” so it’s pretty safe to judge the Act a failure based on the preamble.

Still, many critics like to blame those 2023 bank failures on the first Trump administration for signing into law the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (the Economic Growth Act). But that law did not “gut” Dodd-Frank. In fact, it didn’t repeal one single title (out of 16) of Dodd-Frank. Objectively, it’s difficult to even say that the Economic Growth Act “rolled back” any of Dodd-Frank.

The quick version of what happened starts with Dodd-Frank’s requirement to impose “enhanced” regulations for bank holding companies with assets of more than $50 billion. Few seem to recall, but Section 165 of Dodd-Frank authorized the Fed to implement enhanced standards in a tailored fashion based on specific risks for specific companies. Under certain conditions, Dodd-Frank even authorized the Fed to establish an asset threshold above $50 billion.

So, what did the Economic Growth Act do? It essentially changed the threshold for the Fed’s enhanced supervision to $100 billion. It’s important to note, though, that the Economic Growth Act still left the Fed with the discretion to impose enhanced supervision on bank holding companies below the new $100 billion threshold. So, not such a radical change.

Regardless, the dirty little secret is that federal banking regulators didn’t really need Dodd-Frank to implement higher capital and liquidity ratios. In fact, federal regulators started stress tests before the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law.

There are many problems with the existing bank capital regime and with how the Biden administration arbitrarily tried to implement more burdensome capital rules, but those problems go well beyond Dodd-Frank. Most of that capital framework reflects federal regulators’ decision to implement the Basel III framework, which has roots dating back to (at least) the 1980s.

Other Major Dodd-Frank Provisions

Aside from heightened capital standards, two of the main features of Dodd-Frank were the creation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) and Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA). Title I of Dodd-Frank created the FSOC, a body of regulators charged with identifying risks to the financial stability of the United States and preventing the expectation of bailouts. The OLA, created by Title II of Dodd-Frank, was supposed to resolve large financial institutions in the event of their failure.

As we now know, the FSOC completely missed the 2023 banking turmoil, and the OLA has yet to be used. So much for the main pillars of Dodd-Frank. (By the way, Title XI of Dodd-Frank was also supposed to help end Fed or FDIC bailouts. As the 2023 banking crisis proved, Title XI merely formalized the type of collaborative bailout process between federal officials that was used during the 2008 crisis.)

Title VII was one of the other major Dodd-Frank changes. Title VII imposed a requirement to “clear” more over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives through central counterparties (CCPs). Aside from whether Title VII addressed the main causes of the 2008 financial crisis—it did not—it’s difficult to call Title VII a success.

Prior to the crisis, virtually all the counterparties using OTC derivatives were large banks that negotiated their own terms. If federal banking regulators truly needed more insight into those derivatives, they didn’t need any additional authority to get it. And if they wanted to implement higher capital requirements (or liquidity or even margin requirements) for those derivatives, they could have. They were already considered in banks’ capital requirements.

Simply put, Title VII did not reduce the overall risk from these derivatives; it merely concentrated that risk in the CCPs. (It’s also worth noting that the clearing requirement was the reason the Fed urged Congress to include Title VIII in Dodd-Frank, so that the CCPs would be plugged into the Fed in the event of a failure.)

The last major component of Dodd-Frank is the infamous Title X, the one that created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). As I’ve written many times, it was not necessary to create a new government agency for consumer protection. Multiple federal agencies, as well as state agencies, were already carrying out that function. To create the CFPB, Title X consolidated most of the federal consumer protection statutes under the Bureau, but there was no reason it couldn’t have consolidated them under, just for example, the Federal Trade Commission. As for the new “abusive” standard of consumer protection, Dodd-Frank didn’t bother to define it. (Neither has the Bureau.)

The CFPB has been controversial from the beginning, partly because it was created with such an odd “independent” structure. One of the Bureau’s first significant acts was to go against the long-standing interpretation of the federal statute that governed real estate closings. It then retroactively applied its new interpretation and sued a mortgage company for more than $100 million, a lawsuit that ultimately made it easier for a US president to remove a CFPB director.

Controversial structure aside, some folks believe that creating the CFPB addressed the so-called predatory lending practices that caused the 2008 financial crisis. But there are a few problems with that story. First, it defies reason to think that all the borrowers who defaulted on their mortgages in 2008 were simply tricked into buying a home, not realizing they would have to make monthly payments of a certain amount.

Second, even if one believes this view, the supposed fix in Dodd-Frank was to require lenders to meet an ability to repay standard (enforced by the CFPB). But that standard was only an expansion of lending restrictions first implemented by the 1994 Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA). So, again, the idea that Dodd-Frank (or the creation of the CFPB) was a necessary fix rests on shaky ground.

Some folks hold a more subtle version of this so-called predatory lending view. In this telling, the real problem was that lenders failed to explain to borrowers with adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) that their interest rates and mortgage payments might increase. Research has shown, however, that fixed rate mortgages (FRMs) showed just as many signs of distress as did ARMs. Regardless, Dodd-Frank did not outlaw ARMs, and it is undeniable that lenders had to disclose details of those mortgages prior to the 2008 crisis.

Finally, evidence of fraud in the mortgage market prior to the crisis is sparse and most often fails to support widespread consumer-facing fraud of the type prevalent in the predatory lending story. Instead, it shows that lenders (in some cases) ran afoul of their responsibilities to accurately document consumer information for institutional investors purchasing mortgages. For instance, as this US Housing and Urban Development report states, several studies show that “the vast majority of fraud involves misrepresentation of information on loan applications related to income, employment, or occupancy of the home by the borrower.” That’s a problem for the pro-Dodd-Frank camp for several reasons, but mainly because this type of fraud was already illegal prior to the 2008 crisis.

A Final Word on Dodd-Frank

There are many other small provisions of Dodd-Frank that have virtually nothing to do with the 2008 financial crisis. Most people have likely never heard of these provisions, such as Title IX’s securities lending reporting or self-regulatory organization fee filing provisions. These items likely mean a great deal to several financial practitioners, but that makes it very difficult for others to judge whether these provisions were even necessary. Arguably, many of these provisions created a regulatory mess where none previously existed.

Overall, it’s very hard to celebrate the Dodd-Frank Act’s 15th anniversary. The Act was based on a mistaken belief that the 2008 crisis stemmed from unregulated financial markets. It spawned hundreds of separate rulemakings and was the most extensive financial regulatory bill since the 1930s. It expanded the authority of existing federal regulators, created new federal agencies, and altered the regulatory framework for several distinct financial sectors. It imposed unnecessarily high compliance burdens, failed to solve the too-big-to-fail problem, and didn’t end bailouts.

Worse, it further cemented the notion that the federal government should plan, protect, and prop up the financial system. Fifteen years on, the Act stands not as a triumph of reform but as a case study in how sweeping legislation can miss the mark—and make future crises more likely, not less."

Gross(ery) Confusion

"Zephyr Teachout’s NYTs op-ed on grocery store prices is poorly argued.

The food system in the United States is rigged in favor of big retailers and suppliers in several ways. Big retailers often flex their muscles to demand special deals; to make up the difference, suppliers then charge the smaller stores more.

Let’s be clear about what is actually going on. Costco offers its suppliers lower prices in return for bigger orders. There is nothing anti-competitive about volume discounting. Moreover, are firms dismayed or are they eager to sell to big, bad Costco? Google AI gives a good answer:

…firms are eager to sell to Costco because of the immense potential for sales and brand exposure, but they must be prepared to meet stringent requirements, negotiate competitive pricing, and be able to handle high volume and demanding logistics.

Would Americans be better off without Costco? Doubtful given that more than one-quarter of all Americans pay for a Costco membership (either individually or as a family).

Teachout’s idea that suppliers “make up the difference” by charging smaller stores more is also economically incoherent. Profit-maximizing firms already charge what the market will bear. If Costco’s volume justifies a discount, that doesn’t mean suppliers can or should charge higher prices to other buyers. Yes, there are models where costs change with volume but costs could go down with volume and, in any case, those models don’t rely on the folk theory of “making up the difference.”

That’s one of the subtler mistakes. Here’s a more glaring one:

Consider eggs. At the independent supermarket near my apartment, the price for a dozen white eggs last week was $5.99. At a major national retailer a few blocks away, it was $3.99. (For an identical box of cereal, the price difference was $3.) Any number of factors may contribute to a given price, but market power is a particularly consequential one.

Read that again: the firm allegedly abusing market power is the one charging less.

It gets stranger:

New York City has a strong price gouging law on the books, which forbids anyone — suppliers and retailers — from jacking up prices during a state of emergency unless the seller’s own costs have gone up accordingly. The city couldn’t have stopped the bird flu that devastated flocks, but maybe it can stop suppliers from cynically exploiting a crisis to justify exorbitant prices.

This makes two errors. First, she acknowledges it’s not gouging if costs rise—then cites egg prices rising due to the bird flu devastating flocks. That’s literally a textbook case of a supply shock. Maybe some firms exploited the crisis—but eggs rising in price after millions of chickens are killed is the best example you’ve got???

Second, within the span of a few paragraphs, the op-ed veers from claiming large retailers charge prices that are unfairly low to blaming them for charging prices that are too high. I’m surprised she didn’t go for the trifecta and accuse them of colluding to charge the same price."

Wednesday, July 23, 2025

The reduction in the length of the workweek in American manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to economic growth and the increased wages it brought

See Hours of Work in U.S. History by Robert Whaples of Wake Forest University. Excerpt:

"Historically employers and employees often agreed on very long workweeks because the economy was not very productive (by today’s standards) and people had to work long hours to earn enough money to feed, clothe and house their families. The long-term decline in the length of the workweek, in this view, has primarily been due to increased economic productivity, which has yielded higher wages for workers. Workers responded to this rise in potential income by “buying” more leisure time, as well as by buying more goods and services. In a recent survey, a sizeable majority of economic historians agreed with this view. Over eighty percent accepted the proposition that “the reduction in the length of the workweek in American manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to economic growth and the increased wages it brought” (Whaples, 1995). Other broad forces probably played only a secondary role. For example, roughly two-thirds of economic historians surveyed rejected the proposition that the efforts of labor unions were the primary cause of the drop in work hours before the Great Depression."

Did California's Fast Food Minimum Wage Reduce Employment?

Jeffrey Clemens, Olivia Edwards & Jonathan Meer.

"We analyze the effect of California's $20 fast food minimum wage, which was enacted in September 2023 and went into effect in April 2024, on employment in the fast food sector. In unadjusted data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, we find that employment in California's fast food sector declined by 2.7 percent relative to employment in the fast food sector elsewhere in the United States from September 2023 through September 2024. Adjusting for pre-AB 1228 trends increases this differential decline to 3.2 percent, while netting out the equivalent employment changes in non-minimum-wage-intensive industries further increases the decline. Our median estimate translates into a loss of 18,000 jobs in California's fast food sector relative to the counterfactual."

Tuesday, July 22, 2025

Mayor Daniel Lurie: ‘San Francisco Needs to Save Itself’

The new mayor discusses his plans for restoring the city’s quality of life and getting the budget under control. He may have some lessons for New York

By Max Raskin. Mr. Raskin is a co-founder and managing director of Uris Acquisitions and an adjunct professor at New York University School of Law. Excerpts:

"public safety is Mr. Lurie’s top priority. He praises District Attorney Brooke Jenkins: “She believes like I do that, if you commit a crime, there needs to be consequences. I know that that might be shocking to say, but we weren’t doing that before.” Ms. Jenkins has been censured by both the state bar and a state appellate court for overzealous prosecutions—a notable change from her predecessor, Chesa Boudin, the Weather Underground scion who was recalled from office in 2022 for barely prosecuting at all."

"He endorsed Proposition 36, a ballot initiative that passed in November, which increased punishment and allows felony charges for more drug and theft crimes, including recriminalization of shoplifting items worth $950 or less."

"“If you are going to walk into a store and you are going to steal things, there are going to be consequences now in San Francisco and in the state of California.”"

"The mayor has made police hiring a priority. The city is understaffed by about 500 officers below the minimum recommended level of 2,000. One of his policy commitments is to close this gap."

"“Property crime is down 30%. Violent crime is down 20% year-over-year. Car break-ins are at a 22-year low.”"

"“I saw good management when I was living in New York under [Mayor Mike] Bloomberg.” Mr. Lurie’s governing style borrows liberally from the billionaire, who served 12 years starting in 2002."

"In a break with previous administrations that were wary of the technology industry, Mr. Lurie regularly attends tech conferences"

"Whereas Mr. Mamdani castigates billionaires, Mr. Lurie courts them. Everyone from Laurene Powell Jobs to Jony Ive is getting involved in partnerships Mr. Lurie and his head of economic development, Ned Segal (a former CFO of Twitter), are establishing."

"It is unusual to hear a Democrat declare, “The era of soaring city budgets and deteriorating street conditions is over.”"

"A former nonprofit executive, Mr. Lurie proposed cutting nonprofit contracting by $185 million"

"He prefers a technocratic future to a socialistic one, and he wants San Francisco to be its capital."

We’ll All Pay for New York’s Mamdani Folly

The state will lose wealthy taxpayers, and the federal government will have to cough up more aid

By Bennett Nuss. He is an associate with the National Center for Public Policy Research. Excerpts:

"Upstate New York has stagnated economically for nearly two decades. Businesses are leaving, driven away by regulatory and tax burdens imposed by Albany. Buffalo, a midsize city, has been unable to provide enough competitively paying jobs to maintain the economic status quo. Younger people are fleeing the state to look for work in parts of the country with more opportunity and a lower cost of living. As New York state’s average population ages, government’s ability to provide state-run services such as Medicaid—and even low-cost electricity—has deteriorated. The young workers who once supported their community’s amenities have taken their important tax dollars elsewhere."

"Freezing rents eliminates the rationale for owning a leasable apartment, and the property-tax burden would still fall on real estate holders, making every investment a value loss. Further, freezing rents would undermine the rest of Mr. Mamdani’s agenda. If landlords are losing money, the city budget will suffer from reduced revenue from income-tax collections."

"Mr. Mamdani has proposed an additional 2% income tax on New Yorkers making more than $1 million a year. A family making that much is now effectively paying a combined total income tax rate of approximately 44%"

"The city pays for most of the services Albany provides."

"If wealthy New Yorkers flee for sunnier climes, the city will need even more federal dollars to stay afloat."

Monday, July 21, 2025

A Second Push for Mike Lee’s Federal Land Sales

Freeing up a sliver of government holdings to build homes is a good idea. Deregulation can help.

WSJ editorial. Excerpts:

"Only up to 0.5% of federal land could be sold under his plan, none of which would be from protected areas like national parks, forests and wildlife preserves. States and cities would have the right to bid first on any auctioned land, before private developers."

"Since 2020 the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has transferred about 550,000 acres into state, local and private hands, and there’s no sign of hallowed nature preserves being despoiled."

"The federal government owned almost 90% of land in Nevada by 1998, some of which was unused desert abutting the glittering city. When Congress passed a law to streamline land sales to developers, it spurred a home-building boom, with no harm to grazing or hunting grounds."

"auctioning 150 square miles—less than 0.05% of BLM holdings, and a fraction of the amount Mr. Lee’s plan contemplated—could produce up to one million new homes."

How the U.K.’s Sickness Benefits Trap Britons

If middle-class workers were offered significantly more money for signing off sick with depression or anxiety, how many would persist with their not-always interesting jobs?

"The U.K. welfare situation, if anything, is worse than you suggest in your editorial “The Crisis of the Welfare State in Profile” (July 7). Some 3,000 Britons a day are being signed on to a long-term sickness benefit from which they are unlikely to emerge. This typically offers more money and security than full-time work at the minimum wage. The puzzle, surely, isn’t why so many people claim but why so many still work.

I made a film about this last year, arguing that this is a story of good people caught in a bad system. The government invites citizens to take the money: There is an 80% success rate, with 63% put on the highest tier. In-person interviews have been replaced with a cursory phone call, whose questions and accepted answers are easily found online.

It’s easy to be shocked at the figures, but they aren’t difficult to understand. If middle-class workers were offered significantly more money for signing off sick with depression or anxiety, how many would persist with their not-always-interesting jobs?

Last week’s parliamentary debacle shows that Prime Minister Keir Starmer has lost control. He needs to reduce the onflow, but the welfare system is guarded by activists who successfully sue government ministers who try to reform.

We know what will happen now. Mr. Starmer’s own officials project that 4.1 million will be on out-of-work sickness benefit by the next election, up from 3.5 million today. The waste of money, while shocking, isn’t as scandalous as the waste of life, the disfigurement of local economies. A quarter of Birmingham, the U.K.’s second city, is now on out-of-work benefits. In Manchester, Glasgow and Liverpool, it’s 1 in 5. The resulting vacuum in the labor market has sucked in unprecedented levels of immigration.

The result isn’t simply social and economic calamity but the conditions for a political backlash far deeper than the country experienced last year.

Fraser Nelson

London

Mr. Nelson is a columnist for the Times of London."

Sunday, July 20, 2025

Immigration Raids Reveal Holes in Government’s Tool to Verify Workers

E-Verify can be circumvented with use of stolen identities, false documents

By Paul Kiernan and Robert McMillan of The WSJ. Excerpts:

"The program, called E-Verify, has vulnerabilities that enable migrants in the U.S. to illegally obtain jobs at American companies."

"E-Verify, which matches names to Social Security numbers, has limited access to many other official databases with personal information. It doesn’t use biometric evidence or, in many cases, a photo to verify a new hire’s identity. It can thus be circumvented with a stolen Social Security number and fake driver’s license"

"In 2010, a USCIS contractor found roughly half of unauthorized workers run through E-Verify received an inaccurate finding of being legally employable, primarily because of identity fraud."

"E-Verify can check if someone’s name matches with their Social Security number. But it can’t perform photo-matching for state-issued IDs such as driver’s licenses. According to DHS, 10 states don’t share driver’s license data with the system.

E-Verify processed more than 43 million workers in fiscal 2024, finding 98.5% of them “confirmed as authorized to work.” But a 2021 audit by the DHS inspector general found 54% of all reviewed individuals proved their identity with a driver’s license, which—unlike a federal document such as a passport—can’t be compared with photos in government systems.

That means clearing E-Verify can be as easy as obtaining the name and Social Security number of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident, and printing that information on a fake ID."

Trump’s Unsung Economic Booster: Deregulation

Nuclear power exemplifies how revamping dated and onerous rules could kick-start investment and innovation

By Greg Ip. Excerpts:

"What level of radiation may a U.S. nuclear power plant emit? “As low as reasonably achievable,” the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has long declared."

"There is little consensus that radiation at extremely low levels is harmful."

"Yet the persistence of the standard is one reason why nuclear power plants cost so much and take so long to build."

"Since then [1978], just a handful have been approved."

"NRC’s radiation standards, which are often lower than natural background levels"

"Whether a rule’s costs are worth those benefits is often a judgment call."

"cost-benefit analysis has only an indirect link to actual economic output."

"“anything that goes into a reactor that’s safety relevant has to be nuclear-certified with incredibly strict quality control,” said Ted Nordhaus, founder of the Breakthrough Institute, who has written extensively on nuclear power. This slows deployment and innovation."

Saturday, July 19, 2025

Comparing China to other Majority-Chinese Jurisdictions (they have more economic freedom than China itself and much higher per capita GDPs)

"When writing about Argentina a few days ago, I used this weight-loss analogy to explain that Javier Milei has some amazing accomplishments, but that he can’t rest on his laurels.

Imagine going to a doctor and finding out you have all sorts of health problems because you weigh 400 lbs. You decide you need to get serious (the diet-and-exercise equivalent of electing Milei) and you weigh 300 lbs. at your next appointment. The doctor is very impressed and happy with your progress, but he reminds you that you still need to lose at least another 100 lbs.

This analogy also applies to China.

There was a lot of pro-market reform beginning in 1979, leading to a dramatic increase in economic freedom. This led to spectacular results, such as rapid growth, rising incomes, and plummeting poverty.

Call it the Chinese Miracle. It is akin to dropping from 400 lbs to 300 lbs.

Unfortunately, even though the doctor advised the patient to lose another 100 lbs., that hasn’t happened.

Economic freedom in China has increased in the past two decades, but only by a very small amount. If we stick with our analogy, the patient lost 5-10 more lbs., but is still overweight.

I’ve decided to write on this issue today for two reasons.

- First, I’m actually in China for some lectures about the desirability of further economic liberalization.

- Second, I saw this tweet about how Chinese people outside of China are far richer than Chinese people in China.

I decided to expand on this chart, using the Maddison database, and using data that goes all the way back to 1950. And I also included Hong Kong since it is another majority-Chinese jurisdiction.

Lo and behold, the only Chinese nation that isn’t rich is…drum roll…China.

There’s an obvious lesson to learn.

Note that I included numbers on the right side of the chart. Those are the economic freedom rankings from the Fraser Institute.

Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong all rank very highly. China, on the other hand, is only #104, in the bottom half of the world for economic freedom.

Maybe, just maybe, that explains why the Chinese are rich everyone in the world other than China. The moral of the story is that our patient is much healthier today than 50 years ago. However, it’s time to get back on the treadmill and lose more weight.

P.S. Here’s some interesting data on China and Poland.

P.P.S. I shared data back in 2016 showing that Chinese-Americans were very economically successful. And more-recent data confirms this to be the case."